Right Against Exploitation (Article 23 And 24) under Indian Constitution with landmark cases

- Constitutional Law Blogs Subject-wise Law Notes

- September 4, 2020

There was no connection to slavery or the prevalent custom of forced labour in every region of India when the Constitution was implemented. The National Independence Movement has been a driving power against such policies since the twenties of this century.

In the West of India, which during the pre-Independence days was the Princely States cluster, for example , workers who were working for a specific tenant were not permitted to leave him for employment elsewhere. There were, however, several areas of the country where the “untouchables” had been exploited by the higher class and the rich classes in various ways.

This restriction was very often so severe, and the dependence of the workers on the master was so absolute that in fact he was a slave. These practices were supported by local law.

Evils like the Devadase system, which dedicated women in the name of religion, to Hindu deities, to idols, worship objects, temples, and other religious institutions, under which women were the victims of lust and immorality in certain parts of southern and western India, instead of living a life of dedication, self-renunciation, and piety.

Article 23 in The Constitution Of India 1949

Prohibition of traffic in human beings and forced labour

(1) Traffic in human beings and begar and other similar forms of forced labour are prohibited and any contravention of this provision shall be an offence punishable in accordance with law.

(2) Nothing in this article shall prevent the State from imposing compulsory service for public purpose, and in imposing such service the State shall not make any discrimination on grounds only of religion, race, caste or class or any of them.

Article 24 in The Constitution Of India 1949

Prohibition of employment of children in factories, etc

No child below the age of fourteen years shall be employed to work in any factory or mine or engaged in any other hazardous employment Provided that nothing in this sub clause shall authorise the detention of any person beyond the maximum period prescribed by any law made by Parliament under sub clause (b) of clause ( 7 ); or such person is detained in accordance with the provisions of any law made by Parliament under sub clauses (a) and (b) of clause ( 7 ).

Article 23(1) does not impinge on a law that punishes a individual for failing to provide personal services on the grounds of caste or class alone.

1. Traffic in human beings : the term ‘human trafficking’ generally referred to as slavery means that sex beings are purchased and sold as though they were chattels, and this custom is legally abolished.

The term often refers to trafficking in women for unethical reasons

2. Forced Labour : Exusdem generis could be translated as “all types of forced labour in a related way” in Article 23(1). The type of “forced labour” discussed in this Report may have something to do with human or beggar trafficking.

There is one loophole to the ban against forced labour. The State can enforce a public mandatory service pursuant to Article 23(2).

The Supreme Court ruled in the Peoples Union for Democratic Rights v Union of India [1] that Article 23(1) targets forced labor, as it can manifest. It therefore prevented begar as well as all unwilling jobs, whether paying or not, from being overwhelmed. If a individual is compelled to operate, the sum of money received shall be immaterial.

Article 23 of the Constitution forbids slave labor and requires the crime to be punished in compliance with rule 4 for the violation of that prohibition. Although the prohibition against slavery is total, there is one exception that is made to the prohibition against forced labor; that is, if that service is required for public purposes the State can enforce a mandatory service.

After the constitution, the initial draft and the Constituent Assembly, led by Dr. B.R., is regarded as any exception. Throughout the sense of “pubic intentions,” Ambedkar has followed subclause (2).

In Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union of India [2], the Supreme Court observed that the State was in violation of Articles 21 and 23 when it refused to recognize the bonded workmen, free them from slavery or rehabilitation of them as contemplated under the 1976 Bonded Labour System[Abolition] Act.

Article 23 of the Constitution provides for forced labor and requires any violation of such a prohibition to be a criminal crime pursuant to law Although banning trafficking of human beings is absolute, the prohibition of force-work is subject to one exception, that is to say, if such service is required for a public reason, the State may enforce a compulsory service.

In the initial draft and after complete discussion, the Constituent Assembly led by Dr. B. R. was found to be an anomaly to the constitution. Ambedkar accepted clause (2) on “pubic intentions.”[3]

Article 23 (2)

Clause (2), except clause ( 1), requires the State to enforce a compulsory public service. The State shall, however, not discriminate on the basis of faith, ethnicity , sex, gender or any other, when enforcing such a compulsory facility.

The word ‘public intent’ encompasses any goal or objective which explicitly and fundamentally concerns the common good and not the specific good of individuals. The priorities set forth in section IV of the Constitution concerning the Regulatory Concepts of Public policy would involve social or economic goals.

M.P. State in Devendra v Nath Gupta [4]. The Madhya Pradesh High Court ruled that, even though there was no allowance, teachers were expected to provide a service for “public purposes,” including education surveying, family planning, list of electors, general elections, etc. that did not contravene Article 23.

The High Court in Calcutta, Dulai Shamanta v District Magistrate [5], Howrah observed that it was not prohibited for a public benefit, because it was not begar or trafficked by the State or was not enforced by the Constitution of Article 23.

In the same way, Durbar Goala v Union of India [6]holds that there is no forced labor, or begar, if a individual willingly decides to do work or to do extra work to gain other return benefits.

In Raj Bahadur Case [7]it was held that Article 23 specifically prohibits traffic in human beings or women for immoral purpose.

This article, as laid down in Articles 39(e) and 39(f) of the State Principles of Directive, allows for the security of children’s safety and power under the age of 14.

The Supreme Court in Peasants Union for Democratic Rights v. Union of India (AIR 1982 SC 1473) ruled that building work was unsafe in areas where children under the age of fourteen should not be working, and that the prohibition inherent in Article 24 should be extended to everyone, including State or private persons, unambiguously and unambiguously.

India is a federal republic, so child slavery is a subject that can be legislated over by the central and state governments. The most important regional regulatory changes are: the 1948 Factories Legislation: The Act bans the work in factories of children under the age of 14. The law also sets out guidelines for who should be working in a business of pre-adults aged 15-18 years.

In M. C. Mehta v. Tamil Nadu Government , M. Public Prosecutor. C. Mehta has submitted a PIL pursuant to Article 32 and has told the Court how Sivakasi Cracker Factories is engaged in the girls. While the Constitution bans the slavery and recruitment of children pursuant to Article 24, it also requires the State to provide them in compliance with Article 41 with free and mandatory schooling, although a substantial number of children are already employed in unsafe areas. In spite of several State Governments banning child labor, the problem of child labour persisted unsolved and is every day a danger to society, notwithstanding the Constitutional requirements and numerous legislation. It was held by Hansaria J. that-

“The children below 14 years cannot be employed in hazardous activities and state must lay down certain guidelines in order to prevent social, economic and humanitarian rights of such children working illegally in public and private sector. Also, it is violative of Article 24 and it is the duty of the state to ensure free and compulsory education to them. It was further directed to establish Child Labour Rehabilitation Welfare Fund and to pay compensation of Rs. 20,000 to each child.”

In People’s Union for Democratic Rights v. Union of India, some people including few children below the age of 14 were employed in the construction work of the Asiad Project in Delhi. It was contended that the Employment of Children Act, 1938 was not applicable in the case of children employed in construction work since construction industries were not specified in the schedule of the Children Act. Bhagwati J. held that-

“The contention given by the Government is not at all acceptable. The construction work is hazardous employment and therefore, the children below 14 years must not be employed in the construction work even if the construction work is not specifically mentioned under the schedule of the Employment of Children Act, 1938. The State Government is advised to take immediate necessary steps in order to include the construction work in the schedule of the Act and to ensure that Article 24 is not violated on any part of the country.”

The poorer parts of society continue suffering some severe problems under Articles 23 and 24 of this Convention against trade in and child labor. Such actions are constitutionally prohibited by statute, as well as the ground rules and requirements laid down in the Protection to Slavery Legislation, which are also protected by judicial proceedings in Parliament in the context in Slave Labor Emancipation Act of 1976 which Child Labour Act of 1986.

They must all be conscious that child trafficking is unethical and this recognition will not only be limited to media commercials. This will be applied to the towns. For poor women and girls, groups of women should be formed. I believe that if we listen, we, the young, will make a huge difference. That is the only way for India to become a nation in which all its citizens live equal lives without fear of exploitation.

I feel that if one’s life were subject and at the whim of another individual, the concept of equality before law, fair law rights, and any other basic right in the matter will have little sense. Whilst this constitutional right guarantees the security of the government’s people , India also has a long way to go towards zero oppression.

[1] AIR 1982 SC 1473

[2] AIR 1998 SC 3164

[3] De, D. J. The Constitution of India,1179

[4] AIR 1983 MP 172

[5] AIR 1958 Cal 365

[6] AIR 1952 Cal 496

[7] AIR 1953 Cal 496

Author- Pragya Jaishwal (Symbiosis Law School, Noida)

You might like

Will Lawyers Be Replaced by AI?

Alienee Meaning in Law

What is Wednesbury Principle?

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Name *

Email *

Add Comment *

Post Comment

- Our Selections

- About NEXT IAS

- Director’s Desk

- Advisory Panel

- Faculty Panel

- General Studies Courses

- Optional Courses

- Current Affairs Program (CA-VA)

- Mentorship Program (AIM)

- Interview Guidance Program

- Postal Courses

- Prelims Test Series

- Mains Test Series (GS & Optional)

- ANUBHAV (All India Open Mock Test)

- Daily Current Affairs

- Current Affairs MCQ

- Monthly Current Affairs Magazine

- Previous Year Papers

- Down to Earth

- Kurukshetra

- Union Budget

- Economic Survey

- Download NCERTs

- NIOS Study Material

- Beyond Classroom

- Toppers’ Copies

- Student Portal

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Right against exploitation (article 23 to 24): meaning, provisions & significance.

The Right Against Exploitation , enshrined as a fundamental right in the Indian Constitution, plays a crucial role in ensuring human dignity, freedom, and social justice . This right acts as a guardian which protects the individual from the shackles of forced labor, human trafficking, and child exploitation. This article of Next IAS delves into the nuances of provisions related to Right Against Exploitation, their meaning, significance, exceptions, and more.

Meaning of Right Against Exploitation

The Right Against Exploitation is a fundamental human right that aims at protecting individuals from various forms of exploitation . It prohibits practices that lower the dignity of human beings. The essence of this right lies in safeguarding the dignity, freedom, and well-being of every individual, particularly vulnerable segments of society, by ensuring that they are not subjected to coercion, abuse, or dehumanization.

Right Against Exploitation in India

The Right Against Exploitation is a Fundamental Right enshrined in the Constitution of India. The detailed provisions related to the Right Against Exploitation contained in Articles 23 to 24 of the Constitution serve as a bulwark against various forms of exploitation. Together, they ensure the protection of individuals’ rights and dignity and uphold the principles of social justice.

Right Against Exploitation: Provisions under the Indian Constitution

Prohibition of trafficking in human beings and forced labor (article 23).

- This provision prohibits trafficking in human beings, and all forms of forced labor such as begar, bonded labor , etc . Any violation of this provision shall be an offense punishable by law.

- This right is available to both citizens and non-citizens.

- It protects the individuals not only against the actions of the State but also against the actions of private persons.

Traffic in Human Beings

- selling and buying of men, women, and children as commodities,

- immoral trafficking in women and children, including prostitution,

- the practice of devadasis,

- the practice of slavery, etc.

- To punish these Acts, the Parliament has enacted the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act of 1956.

Forced Labour

- Forced Labour : The term ‘ forced labor ’ means compelling a person to work against his/her will by using physical force, legal force, or compulsion of economic circumstances such as working for less than minimum wages. Some examples of Forced Labour include Begar, Bonded Labour, etc.

- Begar : The term ‘ begar ‘ refers to a peculiar form of forced labor that was prevalent in India during the time of the Zamindari System. Under it, the local zamindars used to force their tenants to render services without any payment or remuneration.

- Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976,

- Minimum Wages Act, 1948,

- Contract Labour Act, 1970,

- Equal Remuneration Act, 1976.

- Exception : An exception to this provision is that the state can impose compulsory service for public purposes such as military service , social service, etc , for which it is not bound to pay. However, in imposing such service, the state cannot discriminate based only on grounds of religion, race, case, or class.

Prohibition of Employment of Children in Factories, etc. (Article 24)

- This provision prohibits the employment of children under the age of 14 in factories, mines, or other such hazardous activities. However, it does not forbid their employment in harmless or non-hazardous activities.

- Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986 and its further amendments.

- Employment of Children Act, 1938

- Factories Act, 1948

- Mines Act, 1952

- Merchant Shipping Act, 1958

- Plantation Labour Act, 1951

- Motor Transport Workers Act, 1951

- Apprentices Act, 1961

- Bidi and Cigar Workers Act, 1966

- The creation of a Child Labor Rehabilitation Welfare Fund in which the offending employer deposits a specified amount of fine for each child employed by him.

- National Commission and State Commissions for the Protection of Child Rights have been established.

- Children’s Courts have been established for speedy trial of offenses against children.

Significance of Right Against Exploitation

- Protection of Human Rights – The right against exploitation safeguards individuals from various forms of exploitation, ensuring their fundamental rights and dignity.

- Prevention of Human Trafficking – By prohibiting trafficking in human beings, this right helps prevent the illegal and immoral trade of individuals for forced labor, slavery, or other purposes.

- Elimination of Forced Labor – It aims to eradicate forced labor practices, such as bonded labor and begar, ensuring individuals are not subjected to work against their will without remuneration.

- Safeguarding Children – This right prohibits the employment of children in hazardous occupations, protects their physical, mental, and emotional well-being, and ensures their access to education and a healthy childhood.

- Promotion of Social Justice – By holding both the state and private individuals accountable for exploitation, this right contributes to fostering a more just and equitable society.

- Support for Vulnerable Populations – It provides crucial support and protection to vulnerable groups, including women, children, and marginalized communities, who are often targets of exploitation and abuse.

- Promotion of Ethical Labor Practices – By prohibiting exploitative labor practices, this right encourages the adoption of ethical labor standards and practices , promoting fair treatment and just compensation for all workers.

The Right Against Exploitation enshrined in the Indian Constitution serves as a bulwark against various forms of exploitation, ensuring the protection of individuals’ rights and dignity . By safeguarding against forced labor, human trafficking, and child exploitation , this fundamental right upholds the principles of social justice and human rights within society. Through its provisions, India reaffirms its commitment to fostering a just, equitable, and compassionate society based on dignity, fairness, and compassion.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Which three evils are tackled by the right against exploitation.

The Right Against Exploitation tackles three primary evils: Forced Labor – It ensures individuals are not compelled to work against their will. Human Trafficking – It prevents the illegal trade and exploitation of individuals Child Exploitation – It safeguards children from hazardous employment and abusive practices.

Latest Article

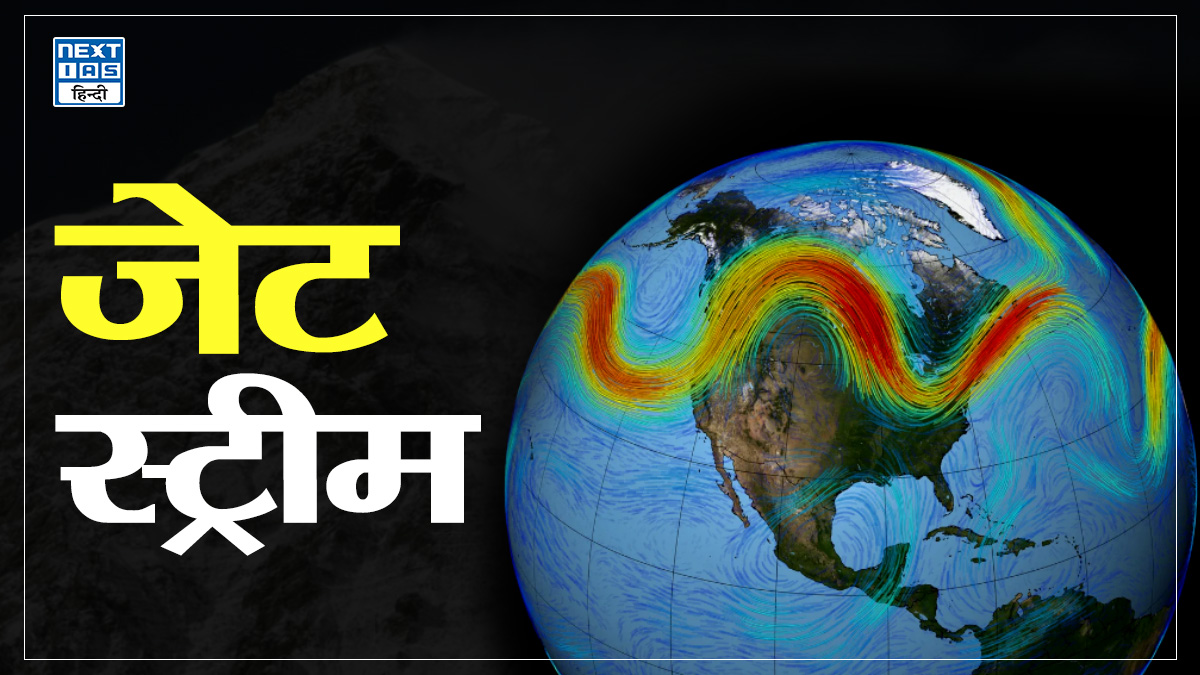

जेट स्ट्रीम : अर्थ, विशेषताएँ, भूमिका और अधिक

एल नीनो, ला नीना और दक्षिणी दोलन

Submarines: About, Types & More

Arrival of the British in India

Arrival of the French in India

भारत में गर्मी का मौसम

Explore Categories

- Art and Culture

- Disaster Management

- Environment and Ecology

- Important Days

- Indian Economy

- Indian Polity

- Indian Society

- Internal Security

- International Relations

- Science and Technology

Subscribe to our Newsletter!

- Increase Font Size

19 Rights against Exploitation (Articles 23-24)

Dr. Rajinder Kaur

Introduction:

The Fundamental Rights enacted in Part-III includes basic inherent human rights which an individual posses. These rights operate as limitations on the powers of the State and impose negative obligations on the State not to intrude on individual liberty. But under Part-III there are certain Fundamental Rights bestowed by the Constitution which are enforceable against the entire world and they are found inter-alia in Article 17, 23 and 24.1 Article 23 was incorporated in the Constitution to prohibit traffic in human beings and begar and other similar forms of forced labour.

3. Prohibition of traffic in human beings and forced labour (Article 23)

3.1 Article 23 and Constituent Assembly

Article 23 of the Constitution of India, 1950 prohibits traffic in human beings, beggar and other similar form of forced labour. The right against exploitation was mentioned in the drafts prepared by B. R Ambedkar, K M Munshi and K T Shah. While Ambedkar draft simply provided that subjecting a forced labour or to involuntary servitude would be an offence. K.M Munshi draft was more elaborative containing provisions for the abolition of all forms of slavery, traffic in human beings and compulsory labour. K. T Shah expressly forbade slavery of any kind but also recognized the rights of Government to conscript by law the man power of the country for the purposes of national defence , social service or for meeting a sudden emergency.2 The provision finally drafted by the sub-committee was as follows:

(a) Slavery

(b) traffic in human being

(c) the form of forced labour known as beggar

(d) any form of involuntary servitude except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted,

Are herby prohibited and any contravention to this prohibition shall be an offence.

Explanation: Compulsory Service under any general scheme of education does not fall within the mischief of this clause,

(2) Conscription for military service or training or for any work in aid of military operation is herby prohibited.

(3) No person shall engage any child below the age of 14 years to work in any mine or factory or any hazardous employment.

The provisions relating to slavery and involuntary servitude in Clause (1) were based upon the thirteenth amendment of US Constitution.4 As far as prohibition of conscription for military service or training contained in sub-clause (2) there was no precedent available. On the other hand some of the Constitutions like Swiss (article 18 para1) 5 , Czechoslovakian (art 127 para1) 6 and Chinese (article 20) 7 contained provision imposing compulsory military services on their citizens.

The Chairman of the committee appointed a small adhoc committee consisting of Mrs. Hansa Mehta, Rajagopalchari and Govind Ballabh Pant to consider the matter and prepare a suitable draft. The committee redrafted the explanation to clause (1), omitted Clause (2).The redrafted provision again came up for discussion Assembly on May 1, 19479 and it turned as clause 17 in the Draft constitution prepared by the draft committee.

17(1) Traffic in human being and begar and other similar form of force labour are prohibited and any contravention to this provision shall be an offence punishable in accordance with Law.

(2) Nothing in this article shall prevent the state from imposing compulsory services for public purpose.

In imposing such services the state shall not make any discrimination on the ground of race, religion caste or class.10

Draft article 17 again came up for consideration in Assembly on Dec 03, 1948. Karimuddin desired to qualify prohibition of begar by the words except as a punishment for crime so as the enable jail authorities to extract work from prisoners.11 Several other members sort to extend the scope of the provision related to traffic in human being to certain specific practices like serfdom devdasis system and others form of enslavement and degradation. 12 During the debate on the draft articles, several members welcomed it as a charter of liberty for downtrodden people who have so far suffered from the imposition of forced labour in one form or the other at the hands of princes and zamindars. Gurmukh Singh Musafir welcomed the article and referred to two points: (i) that the course of prostitution should be specifically abolished and (ii) the provision must be made for compensation being paid for compulsory services. B. Dass suggested that particular attention to be paid on prohibition of traffic in women. Kamath raised the point that word begar has not been define in the constitution.

Concluding the debate Ambedkar rejected all the amendments expect the one moved by K.T.Shah for the inclusion of the word “Only” after the word “discrimination on the ground” in clause (2) of the Article. At the revision stage the drafting committee renumbered article 17 as article 23 which read as follow

(1) Traffic in human beings and begar and other similar forms of forced labour are prohibited and any contravention of this provision shall be an offence punishable in accordance with law.

(2) Nothing in this article shall prevent the State from imposing compulsory service for public purposes, and in imposing such service the State shall not make any discrimination on grounds only of religion, race, caste or class or any of them.

Article 23(1) prohibits traffic in human beings and begar and other similar form of forced labour and provides that the contravention to the same will be punished in accordance with law. But it took 25 years to make specific law the above referred contravention initially through the ordinance i.e. the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Ordinance, 197514 and finally was replaced by the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976.

3.2 Judicial Intervention:

The Constitution doesn‟t specifically define the word „begar‟. In the case of S. Vasudevan and Ors. v. S.D. Mital and Ors 15 Tambe, J. referred to Molesworth to define the word begar which says that ‘Labour or service exacted by a Government or a person in power without giving remuneration for it.” He further quoted Wilsons Glossary for the meaning of the word ‘Forced labour” which means, one pressed to carry burden for individuals or to public; under old system when pressed for public service, no pay was given.” The Bombay High Court observed that, to bring the case within the mischief which clause (1) of Article 23, it must be established that a person is forced to work against his will and without payment.

A custom which was prevalent in ManipurState came to the notice of the Court in KahaosanThangkhul v. Simirei Shailer 16 in which each of the village holders in the village have to offer one day‟s free labour to the headman of the village. The appellant in that case denied to tender one day‟s free labour to the headman and challenged validity of the custom as being in contravention to the Article 23(1) of the Constitution. The court upheld that the custom is violative of Article 23(1) of the Constitution.

The landmark case in this context popularly known as Asiad Games Case ,17 was result of Public interest litigation which was initiated with the letters addressed to Justice P N Bhagwati. The letter was based on an exploration by three social scientists, alleging the violations of labour laws by the Union of India, the Delhi Development Authority and the Delhi Administration. The primary accusation was that the contractors paid wages to jamadars – crew bosses – who subtracted a commission and then made the payments to the workers which were less than the minimum wages prescribed i.e. 9.25 rupees per day. The question before the Supreme Court was whether Article 23 can be made applicable to a condition where workers are paid less than the minimum wage.

While delivering the judgment the Court took into consideration the International instruments i.e. International Labour Organization Convention 1929, the European Convention for Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, 1950 and the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights, 1966 and observed that the Article 23 prohibits the forced labour in whatever form it is found or existed. The Court also relied upon the two US peonage cases – Bailey v. Alabama 18 and Pollock v. Williams 19 and further held that Article 23 was anticipated to cover all forms of forced labour even if the workers or persons have entered voluntarily.

The Court focused the study on the specific term i.e. force in forced labour and also highlighted the different ways through which it force can be used which can be physical compulsion, hunger and poverty and economic situation can also be the reason. In all these circumstances a person doesn‟t have an option but to accept any employment on the wages less than minimum wages. The Apex Court observed that accepting employment less than the minimum wages specified will also fall within the purview of forced labour under Article 23 of the Constitution.

In Sanjit Roy v State of Rajasthan 20 in the present case the state government undertook relief work in a drought hit area manifestly with the aim of providing persons affected with some form of work. The wages paid to the persons employed in the relief work were much less than the minimum wages. The court invalidated that provision of the Rajasthan Famine Relief Work Employees Act, 1964 which exempted the application of the Minimum Wages Act, 1948 to the employment of famine relief work.

In Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union of India 21 public interest litigation was filed by Bandhua Mukti Morcha through a letter to Justice Bhagwati contending the situation of huge numbers of labourers working in inhumane circumstances as bonded labourers in the stone quarries of Haryana. It was further contended that it was in gross violation of the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976.The Court assumed the letter as a writ petition. The court also appointed a commission comprising of two lawyers to to check out the situation of stone quarries. The commission bring into that the workers were working in inhumane conditions where they were not having clean water to drink, living in appropriate places without basic amenities.

The Haryana Government, with a view to avoid the rehabilitation requirements for bonded labourers obligatory through the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, the State turned with a new argument that they may fall under forced labour but not bonded labour. The Court initially highlighted that the Act was made with the objective to give effect to Article 23 of the Constitution which forbid traffic in human beings and begar and other similar forms of forced labour. The Court observed that it is patently obvious that the “bonded labour is a form of forced labour”. The Court further highlighted the situation that the worker is an illiterate person who will not have documentary proof to prove the advance taken. The Apex Court observed it is an unkind to give benefit of the above referred social welfare legislation through the cumbersome process of litigation involving process of trial and procedure of recording evidence. Such kind of application process will practically result into non implementation of this Act. Therefore, in such circumstances whenever the labourer is made to provide forced labour, the court will presume that it is the result of consideration of an advance or other economic consideration received by him.This is a rebuttal presumption but with cogent evidence.

In Neeraja Choudhary v. State of M.P 22 the court reasserted its stand in the following word same view that isunkind to give benefit of the social welfare legislation through the cumbersome process of litigation involving process of trial and procedure of recording evidence. Justice Bhagwati further observed that whenever it is revealed that a labourer is providing forced labour, there will be presumption in the Court that he is required to do so in consideration of an advance received by him and is, therefore, fall with in the purview bonded labourer. Unless the employer or the government rebuts this presumption, the court shall presume that the labourer is a bonded labourer entitled to the benefit of a provision of the Act. The court has, issued direction to the State government to include in the vigilance committee representatives of Social Action for identification, release and rehabilitation of bonded labourer. It also made a number of suggestions and recommendations for improving the existing state of affairs. One such suggestion related to their re-organization and activation of vigilance committees.

In the case Government Engineering College v. Sreenivasan 23, the Court has observed that ‘Minimum Wages Act is a pre-constitution enactment and the provisions contained therein have to be read subject to the provisions of the Constitution where a person is compelled by force of circumstances like hunger or poverty to provide labour or service to another for wages which is less than the minimum charges, the labour or service provided by him clearly falls within the scope and ambit of the words ‘forced labour’ under Article23 of the Constitution of India. In such a situation unless the infraction of the Constitutional rights is writ large, this court has the obligation to enforce the Constitutional guarantee contained in Article23 of the Constitution of India.’

In another landmark case the President Cinema Workers Union Affiliated to BharatiyaMazdoorSangh v. The Secretary Social Welfare and Labour Department and Ors24 the Notification was issued in the month of July 1992 fixing the minimum wages and thereafter, no fresh Notification is issued by the State Government fixing the minimum wages for the Cinema workers till this day. Looking to the said intention of the Legislature, while enacting the Minimum Wages Act, 1948, the Government should not have failed to review the minimum rates of wages fixed by it as back as in the year 1992. It is unfortunate that there is no revision of minimum wages for the last 13 years. The Government cannot take shelter under proviso to Section 3(1) (b) of the Act for postponing to issue the revised notification after five years. The Government cannot indefinitely postpone the issuance of revised notification fixing minimum wages, particularly in view of the intention of the Legislature. The Government shall as far as possible review the minimum rates of wages at such intervals not exceeding five years. Wherever, for any reason, the wages are not reviewed within the period of five years the same have to be reviewed within the reasonable period thereafter. In this case, as aforesaid, there is no revision of minimum wages for 13 long years. Definitely, the period of 13 years cannot be said to be reasonable period. In view of the above, it is clear that the Government’s inaction in this case is violative of Article23 of Constitution of India.

Remuneration, which is not less than the minimum wages, has to be paid to anyone who has been asked to provide labour or service by the state. The payment has to be equivalent to the service rendered; otherwise it would be „forced labour‟ within the meaning of Article 23 of the Constitution. Whenever during the imprisonment, the prisoners are made to work in the prison; they must be paid wages at the reasonable rate. The wages should not be below minimum wages. In Constituent Assembly debates this issue was specifically pointed out but later on dropped during further discussion.

In the case of Re Prison Reforms Enhancement of Wages of Prisoners etc 25 this Court has been receiving petitions from prisoners in the various jails of the State either directly or through the grievance deposit boxes maintained in the jails on the issue whether prisoners were entitled to reasonable wages for the amount of labour extracted from them while serving the sentence. The approach to the question of payment of wages in the different, countries of the world differs widely. From 1877 to 1913 some local English prisons used to pay wages or gratuity, however small, to the inmates. This practice was totally abolished in 1913 but re-introduced later in response to a fairly large body of public opinion. The wages paid in the United States of America is said to be meagre. Wages are paid in the shape of compensation in Belgium and Japan, premium’ in Sweden, gratuity in China, bonus in Thailand and reserve in Portugal. But the wages supplied in all these countries are meagre or inadequate and are not in recognition of the right of the prisoner to claim such wages. Hence to sustain a claim of the prisoner for reasonable wages, wages which a man outside the prison would obtain by negotiation supplemented by the labour and welfare laws of the country there is no precedent brought to our notice, perhaps the question is raised by the prisoners in this form for the first time. The court referred to the case of D. B. M. Patnaik v. State of A. P. 26 that a inmate does not surrender his citizenship nor does he lose his civil rights, except such rights as freedom of movement, which are necessarily lost because of the very fact of imprisonment. The consequence is that to deny a prisoner reasonable wages in return for his work will be to violate the mandate in Article 23(1) of the Constitution. Consequently the State could be directed not to deny such reasonable wages to the prisoners from whom the State takes work in its prisons.

In another important case of Gurdev Singh v. State Himachal Pradesh 28, the court said that Article 23 of the Constitution forbids „forced Labour‟ and mandated that any breach of such prevention shall be an offence liable to be punished in accordance with law. The Court observed that all the inmates of different class in all the jails in the State are entitled to be paid reasonable wages for the work they are called upon to do in the jails and outside the jails. These wages are left to be decided by the State Government within a reasonable period i.e. one year from the date of decision of these cases. However, the prisoners will be paid the minimum wages as notified by the State Government from time to time under the Minimum Wages Act, 1948 from the date of filing of these petitions in this Court. These wages will be worked out within a period of three months from today and deposited in the account of each prisoner.

In the case of State of Gujarat v. Hon’ble High Court of Gujarat 29, a sensitive question which required very circumspective approach mooted before the court. Whether the prisoners, who are under obligation to do labour as part of their punishment, should essentially be paid remuneration for such work at the rates prescribed under Minimum Wages legislation. All the judgments were considered in appeal in this case it was held that it is lawful to employ the prisoners sentenced to rigorous imprisonment to do hard labour whether he consents to do it or not. It is essential that the detainees should be remunerated reasonable wages for the work done by them. In order to decide the quantum of reasonable wages payable to the prisoners the State Government shall comprise wage fixation body. Until the state Government takes any decision on such suggestions every inmate must be paid for the work done by him at such rate or revised rates as the Government fixes in the light of the observation made by the Supreme Court in the Judgment .

Clause (2) of Article 23, an exception to clause (1), enables the State to impose compulsory service for public purpose. However, while imposing such compulsory service, the State is prohibited from making any discrimination on the ground only of religion, race, caste, class or any of them. In Acharaj Singh v. State of Bihar 30 , it has been held that to compel a cultivator to bring food grains to the Government godown without remuneration for such labour, in a scheme for procurement of food grains as an essential commodity for the community, there shall be no contravention of Article 23 of the Constitution because the compulsory service is for “public purpose”. The Calcutta High Court in DulaiShamanta v. District Magistrate, Howrah 31 held that the state is not prevented from imposing compulsory service for public purpose such as conscription for police or military services as this services is neither begar nor trafficking human beings and not hit by Article 23 of the constitution.

In DevendraNath Gupta v. State of M.P 32 the Madhya Pradesh High Court held that the service required to be rendered by the teachers towards educational survey, family planning, preparation of voters list, general elections, etc. were for „public purpose‟ and therefore even if no compensation was paid, that did not contravene Article 23.

The United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, which supplemented the 2000 UN Convention against Transnational Organised Crime was ratified by India in 2011. The party countries to the Protocol are required to penalise all forms of trafficking defined in terms of recruitment, harbouring, or transportation by means of force, fraud, coercion, or abuse of position of vulnerability for purposes of exploitation. Though exploitation was not defined under the Protocol but it includes a minimum forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude, or the removal of organs. In other words, the Protocol is intended to aim trafficking in labour sectors as well.

Bonded labour contacts are not purely economic contracts, which were voluntarily entered by the employees due to economic necessity. Once employees enter into these relationships, they are characterized by multiple asymmetries and high exit costs, which were not a part of the contract, as understood by the employee, at the outset.34 Article 23 of the Constitution is though an economic right applicable against the whole world but its interpretation has been widened by the Supreme Court with the changing time and need. But still even after giving the status of fundamental right from the inception only we are unable to curb the whole problem.

4. Prohibition of Employment of Children in Factories etc (Article 24) 4.1 Article 24 and Constituent Assembly

Prohibition of child labour and provision for compulsory universal, primary education for all children up to the age of fourteen have been advocated long before Independence. In 1906, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, the then President of the Indian National Congress, unsuccessfully urged the British Government to establish free and compulsory elementary education. The movement continued. With the setting up of the Constituent Assembly in 1949, it was resolved that the future Constitution of India would provide for abolishing child labour and ensure compulsory education to children. The reference was made to Article 23 para 2 of the Yugoslavian Constitution in this regard which prohibits the employment of children in mines, factories or other hazardous jobs. 35 The matter was discussed in the Constituent Assembly with all concern. Significantly, the draft constitution prepared by the Drafting Committee contained provisions for prohibition of child labour and for free and compulsory education for children.

Article 1836 of the Draft Constitution provided ban on the employment of children below 14 years of age in any factory or mine or engaged in any other hazardous employment. It reads as:37

No child below the age of 14 years shall be employed in any factory or mine or engaged in other hazardous activities.

Sh. DamodarSwarup Seth while expressing his views with regard to affording protection to children of minor age also suggested an addition to the said article for prohibiting employment of women workers at night in order to protect their health.38

Prof. Shibban Lal Saksena also advocated the amendment proposed by Sh. Damodar Swarup Seth. He said that he was very glad that this article has been placed among fundamental rights. In fact, one of the complaints against this charter of liberty is that it does not provide for sufficient economic rights. If we examine the fundamental rights in the Constitutions of other countries, we will find that many of them are concerned with economic rights. In Russia, particularly, the right to work along with, the right to rest and leisure, the right to maintenance in old age and sickness etc., are guaranteed. We have provided these rights in our Directive Principles, although it was thought, that they should be incorporated in this chapter. Even then, this article 18 is an economic right that no child below the age of fourteen shall be employed in any factory. He further suggested that the age should be raised to sixteen. In other countries, also the age is higher, and they also want that in our country this age should be increased particularly on account of our climate, children are weak at this age and the age should be raised.39

The Constitution as was finally adopted on 29th November, 1949 contained provisions for the protection of children. The Constitution guarantees special protection to children. The relevant provisions in this regard are discussed below:

Article 24 provides that “No child below the age of fourteen years shall be employed to work in any factory or mine or engaged in any other hazardous employment”. It must be noted that this Article does not create an absolute ban to the employment of child labour. In the first place, this Article applies only to children below the age of 14 years. Secondly even in case of the children below 14 years, this Article only prohibits the employment of children in a factory or mine or in any other hazardous employment.

4.2 Judicial Intervention:

In the well known Asiad Project 40 the Apex Court held that Article 24 of the Constitution, which even if not followed up by appropriate legislation, must operate proprio vigore and construction work is included in the hazardous occupations. Therefore, there can be no doubt that even if the construction industry in not mentioned as hazardous activity in the schedule to the Employment of Children Act, 1938, no child below fourteen years can be employed in the construction work. Further, in another case the Hon‟ble Supreme Court observed that it not enough merely to identify and release bonded labourers but it is equally perhaps more, important that after identification and release, they must be rehabilitated, because without rehabilitation, they would be driven by poverty, helplessness and despair into serfdom once again.41

In labourers working on Salal Hydro Project v. State of Jammu and Kashmir and others 42the Hon‟ble Apex Court directed that whenever the Central Government commences a construction project which is likely to last for a substantial phase of time, it should ensure that children of construction workers who are living at or near the project site are given amenities for schooling. The Court further lays down that this may be done either by the Central Government itself, or if the Central Government entrusts the project work or any part thereof to a contractor, necessary provision to this effect may be made in the contract with the contractor. In Rajangam, Secretary, District Beedi Workers Union v. State of Tamil Nadu and others. 43 The Supreme Court observed that tobacco manufacturing was certainly an unsafe occupation to the health of children. As far as possible the children in this avocation should be banned. The employment of child labour in this industry should be closed without delay or it can be dealt in a phased manner which is to be decided by the State Government but the period should not be exceeding three years.

In M.C. Mehta v. State of Tamil Nadu& others 44 case M.C. Mehta, a public spirited lawyer, filed public interest litigation in 1986 against the harrowing practices of employing children in the match, fireworks and explosive factories of Sivakasi in Kamrajar district of Tamil Nadu. The Supreme Court delivered land mark judgement giving the following directions:

- In fulfillment of the legislative intention behind the enactment of the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986, every offending employer must be asked to pay compensation amounting to Rs.20,000/- for every child employed in contravention of the provisions of the Act.45

- As a large number of working children are engaged in such occupations, asking the respective State government to assure alternative employment to an adult would strain the resources of the states. As such, where it is not possible to provide a job to an adult member of the family, the government concerned should, as its contribution/grant of Rs.5000/- per child in the child labour Rehabilitation-cum-Welfare Fund.46

- A survey should be conducted of the type of child labour under issue which should be completed within six months.47

- In case where alternative employment cannot be made available the parent/guardian of the concerned child should be paid the income earned as interest on the corpus of Rs.25,000/- for each child every month. The employment given or payment made would cease to be operative if the child is not sent to school by the parent/guardian.48

- On discontinuation of the employment of the child, free education should be assured in a suitable institution with a view to making him a better citizen.49

In another significant judgment given by the Apex Court on the basis of PIL Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union of India and others 50 , a number of guidelines on the recognition release and rehabilitation of child labour has also been given. The Court, inter-alia , directed the Government of India to organize a meeting with the State Government to come up with the principles/policies for progressive elimination of employment of children below 14 years in all employments consistent with the design laid down in Civil Writ Petition No.465/86. These guidelines were given by the Court in the background of employment of children in the Carpet Industries in the State of Uttar Pradesh. In this case the Court issued the following directions to the Government of Uttar Pradesh:

- Examine the situation of child emoployment.

- Welfare directions to be issued which results into the total exclusion of child below 14 years of age from any kind of employment.

- Provides facilities for education, health, hygiene, healthy food etc.

In Bachpan Bachao Andolan vs. Union of India 51 the Supreme Court observed directed that in the light of infrastructural constraint, the labour Department, Delhi has to commence implementing the Delhi Action Plan by accommodating for the time being about 500 children every month. The Court observed that the Delhi Action Plan lays down a detailed procedure for interim care and protection of the rescued children to be followed by Labour Department as prepared by the National Commission with the modifications mentioned in the judgment and we further direct all the authorities concerned to immediately implement the same.

In another important case Bachpan Bachao Andolan v. Union of India ,52 in this case the Supreme Court of India has taken up the issues of children working in the circus and instructed the government to prohibit the employment of children in the circus business. Until recently, the form of entertainment was exempt from the laws which state that no child under the age of 14 can be placed into labor. However, an amendment passed to bring circuses in line with other industries has been ignored by employers and now the government has been encouraged to impose a complete ban. We plan to deal with the problem of children’s exploitation systematically. In this order we are limiting our directions regarding children working in the Indian Circuses:

- Put into practice the fundamental right of the children under Article 21A is very important and the Central Government must issue suitable notifications prohibiting the employment of children in circuses within two months from today.

- The respondents are aimed to conduct synchronized raids in all the circuses to release the children and verify the contravention of fundamental rights of the children. The salvaged children are to be kept in the Care and Protective Homes till they achieve the age of 18 years.

- The respondents are also directed to speak to the parents of the children and in case they are ready to take their children back to their homes, they may be directed to do so after appropriate authentication.

- The respondents are directed to frame suitable design of rehabilitation of salvaged children from circuses.

To conclude, I would like to quote Dr. Dorothy, a social activist, has said we have got to work to save our children and do it with full respect for the fact that if we do not, no one else is going to do it. 53 The State is not exonerated from its duty by enacting legislation which is not sufficient to achieve the desired goal. To tackle this kind of social problems involvement of society at large is needed. All sections of society, government, elected representatives, trade unions, employers, legal and judicial fraternity, NGOs, academician can play a positive role in sensitizing the society towards hazards of child labour and encourage the reporting of these violations

Home / clat pg / Notes on Right against Exploitation: Article 23 and Article 24 of the Indian Constitution

Notes on right against exploitation: article 23 and article 24 of the indian constitution, introduction.

Right against exploitation is a fundamental right available to citizens of the country. Articles 23 and 24 of the Indian Constitution deal with this right. In this article, we’ll take a look at the provisions under Article 23 and 24 along with a few landmark cases.

Article 23 of the Indian Constitution

Article 23 of the Indian Constitution prohibits trafficking in human beings and forced labor.

Article 23 of the Indian Constitution states:

(1) Traffic in human beings and begar and other similar forms of forced labour are prohibited and any contravention of this provision shall be an offence punishable in accordance with law

The main purpose of this Article is to prevent the exploitation of individuals through forced labor, slavery, and human trafficking. The Government has taken several measures to enforce this provision and provide protection to the victims of such crimes.

The Supreme Court has interpreted Article 23 broadly to include bonded labor and trafficking in human beings. One of the landmark cases related to Article 23 is People’s Union for Democratic Rights v. Union of India in which the Supreme Court held that forced labor was a violation of fundamental rights guaranteed by the Indian Constitution. The case was related to the working conditions of contract laborers who were employed by the Government. The court held that the Government could not exploit the workers and that they were entitled to fair wages and working conditions.

Another significant case is Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union of India , in which the Supreme Court held that bonded labor was a form of forced labor and was therefore prohibited under Article 23. The case was related to the exploitation of workers in stone quarries in the Faridabad district of Haryana. The Court directed the Government to take measures to eliminate bonded labor and provide rehabilitation to the victims.

The Supreme Court has also held that trafficking in human beings violates Article 23. In the case of State of Tamil Nadu v. Nalini , the Court held that trafficking in women for the purpose of prostitution was a violation of their fundamental rights. The case was related to the abduction and trafficking of a young woman who was forced into prostitution.

To further the agenda of prohibiting human trafficking and bonded labour the Government of India has enacted several laws to prevent trafficking in human beings and forced labor.

- The Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956 prohibits prostitution and related activities.

- The Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976 prohibits bonded labor and provides for the rehabilitation of bonded laborers.

- The Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986 prohibits the employment of children in certain occupations and regulates the conditions of work of children in other occupations.

Article 24 of the Indian Constitution

Article 24 of the Indian Constitution prohibits the employment of children below the age of 14 years in factories, mines, or other hazardous employment. The article recognizes the right of children to have a childhood free from exploitation and to receive education and training for a better future.

Article 24 states that:

No child below the age of fourteen years shall be employed to work in any factory or mine or engaged in any other hazardous employment.

The article states that no child below the age of 14 years shall be employed to work in any factory or mine or engaged in any hazardous employment. The provision also applies to the employment of children in any other form of work that is likely to interfere with their education or be harmful to their health or mental or physical development.

The Constitution recognizes that children are vulnerable and require protection from exploitation and abuse. The prohibition of child labour is essential for the development and well-being of children and is in line with the international standards set by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.

In the case of MC Mehta vs State of Tamil Nadu , the Supreme Court held that the employment of children in hazardous industries violated Article 24 of the Constitution. The Court observed that the children employed in hazardous industries were being subjected to inhuman and degrading treatment, which violated their fundamental rights.

In People’s Union for Democratic Rights vs Union of India , the Supreme Court held that the right to education and the right to life with dignity were fundamental rights under the Constitution. The Court held that the employment of children in any work that interferes with their education or mental and physical development violated their fundamental rights.

The Indian government has also enacted laws like the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986, to prevent the employment of children below the age of 14 years in hazardous industries. The Act provides for the regulation of the employment of children in non-hazardous industries and imposes penalties for violations.

The Government also introduced the Child Labour (Prohibition & Regulation) Amendment Act, 2016 and the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Amendment Rules, 2017 to further protect children against exploitation.

In recent years, there has been an increase in the awareness of child labour in India. The Government, along with civil society organizations, has taken several initiatives to eliminate child labour and provide education and training to children. The Government has also launched programs like the National Child Labour Project to rehabilitate child labourers and prevent the exploitation of children.

Click here to find more notes on Constitutional Law

Subscribe to our newsletter and get daily news & updates directly to your inbox!

Please provide a valid email address.

Join our WhatsApp Channel

Join our Telegram Group

Right Against Exploitation

India is currently the world’s largest democracy in terms of population. However, in the past, the country and its people have faced a long history of slavery. The Indian Penal Code, 1860 was a significant legislation that helped to abolish the slavery system in India. Additionally, the framers of the Indian Constitution included the Right against Exploitation under Articles 23 and 24, in order to prohibit any activities that exploit individuals or groups.

The Indian Constitution guarantees dignity and liberty for every citizen, which serves as a barrier against exploitation. This means that every individual is entitled to respect and autonomy, and any actions that infringe upon these rights are prohibited. The Constitution ensures that the exploitation of one’s labor, resources, or person is unacceptable and that the government should provide protection and support to the victims.

- What is meant by "Exploitation"?

Right Against Exploitation – Provisions

Right against exploitation under article 23, traffic in human beings, forced labour, bonded labour system, article 23(2) – exceptions , case studies, people’s union for democratic rights v. union of india (1983), bandhua mukti morcha v. union of india (1984), sanjit roy vs state of rajasthan (1983), deena v. union of india (1983), neerja choudhary v. state of madhya pradesh (1984), right against exploitation under article 24, peoples union for democratic rights v. union of india (1982), mc mehta vs. state of tamil nadu, child labour (prohibition and regulation) act, 1986, amendments in 2016, amendments in 2017, faqs related to right against exploitation, what are articles 23 and 24 of the indian constitution, what does the right against exploitation under articles 23 and 24 of the indian constitution protect against, are there specific laws in place to protect the rights of laborers and children in india, what are some common forms of exploitation witnessed in india, how can we combat exploitation in india, what are the penal actions taken against the violators of articles 23 and 24 of the indian constitution, who can file a complaint against the exploitation under articles 23 and 24 of the indian constitution, what are the remedies available for the victim of exploitation under articles 23 and 24 of the indian constitution, what is meant by “exploitation”.

The term “exploitation” is borrowed from the French language and refers to the act of depriving a person of their rightful share, reward, or remuneration through force or deception. Exploitation occurs when an individual is not compensated for the labor and services they have contributed to the production of wealth. This can include situations where a person is not receiving a fair pay for their work or is being forced to work against their will. Exploitation is the act of depriving a person of their rightful share, reward, or remuneration through force or deception.

The constitution has measures in place to protect vulnerable groups from being taken advantage of and to promote individual freedom.

This can be found in Article 23, which prohibits forms of human trafficking such as forced labor and beggar labor and carries legal consequences for violators.

Article 24 also contains a provision to prevent the exploitation of children by prohibiting the employment of children under the age of 14 in hazardous work environments such as mines or factories.

Prohibition of traffic in human beings and forced labour (1) Traffic in human beings and begar and other similar forms of forced labour are prohibited and any contravention of this provision shall be an offence punishable in accordance with law. (2) Nothing in this article shall prevent the State from imposing compulsory service for public purposes, and in imposing such service the State shall not make any discrimination on grounds only of religion, race, caste or class or any of them.

Article 23 of the Indian Constitution , in its first clause prohibits three forms of exploitation: trafficking, begar, and forced labor. It also states that any violation of this prohibition will be considered an offense. The parliament has the authority under Article 35 to create laws that prescribe punishment for any actions prohibited under Part III of the constitution.

In exercising this power, the parliament has passed several laws that prohibit forced labor, begar, and trafficking. These laws include the Suppression of Immoral Traffic in Women and Girls Act, 1956 and the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976. These laws were passed in accordance with Article 23 to provide legal consequences for those who violate the prohibition on exploitation.

Traffic in human beings refers to the illegal and immoral practice of buying and selling people as if they were merchandise, for use in criminal or unethical activities or other purposes. This includes the trafficking of women for the purpose of sexual exploitation. To address this problem, the Indian Parliament has passed the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956, which aims to combat the trafficking of women and children for immoral purposes.

This Act is a legislation aimed at preventing the exploitation of women and children in the sex trade. It is designed to suppress the organized criminal activity of prostitution and to protect women and children from being exploited in this manner. The Act provides for the punishment of those involved in the trafficking, procurement and management of women and children for prostitution. It also provides for preventive measures and for the rescue and rehabilitation of the victims of such trafficking. It is a criminal offense under Indian law and any person found guilty of the offense is liable to be punished with imprisonment and/or fine.

Begar refers to work that is performed without payment and without the free and informed consent of the person doing the work. It is a form of forced labor where a person is made to work without receiving any compensation for their labor. This practice was common in the former princely states of India. However, it has been abolished by Article 23(1) of the Indian Constitution.

Article 23(1) prohibits forced labor, including begar, and makes it a fundamental right that no person shall be forced to do any labor without fair compensation. The provision aims to protect the rights of workers and to ensure that they are not subjected to exploitative labor practices. The practice of begar is considered as a violation of human rights and it is considered as an infringement of the dignity and freedom of a person.

The government is also responsible for the implementation of the provision to take necessary steps to prevent such practices and to punish those who violate the provision. The provision is also supported by other laws such as the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act,1976 to prevent the exploitation of workers and to ensure fair compensation for their labor.

The phrase “other forms of forced labor” used in Article 23(1) of the Indian Constitution is to be understood as being similar in nature to the terms “begar” and “traffic in human beings.” This means that the type of forced labor prohibited by this Article must be of a similar nature to the forms of begar and human trafficking. The Supreme Court of India has given a broad interpretation to the term “forced labor” in order to encompass a wide range of exploitative practices.

This means that the provisions of Article 23(1) of the Indian Constitution are not limited to the specific forms of forced labor mentioned in the article, but also include other forms of forced labor that are similar in nature. The court has interpreted the term in a manner that encompasses various forms of exploitation, including forced labor and all other forms of forced labor that violate human rights and dignity. This interpretation ensures that the provisions of Article 23(1) are able to effectively protect the rights of workers and to ensure that they are not subjected to exploitative labor practices.

Bandhua Majdoor is another form of forced labor, where a person is obligated to work for another person for an extended period of time, often until a debt is repaid. This system is often used to exploit vulnerable individuals by those who are socially and economically more powerful. To address this problem, the Indian Parliament has passed the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976, which aims to combat the practice of bonded labor.

The Act makes the practice of bonded labor illegal and provides for the release of bonded laborers and their rehabilitation. It also provides for the recovery of wages and other dues of the bonded labourer. This Act also provides for the punishment of those who violate the provision and for the protection of bonded labourers. The Act also provides for the constitution of a Bonded Labour Rehabilitation Fund and the constitution of an Advisory Board to advise the Central Government on the implementation of the Act. The Act is aimed at protecting the rights of workers and to ensure that they are not subjected to exploitative labor practices.

For certain public goods such as national security, eradicating illiteracy, or ensuring the efficient functioning of public utilities like water, electricity, postage, train, and air services, the state may require mandatory services. However, the state is not allowed to discriminate based on religion, caste, race, or class (in a financial context) while imposing such requirements for public reasons.

It is worth noting that sex is not considered a prohibited basis for discrimination, thus women may be excluded from being required to serve in the public sector. To date, India has not passed a similar law at the national level. The only exception to this was a brief period in Nagaland, where a legislation existed that allowed for able-bodied individuals to be called upon to help with blood impediments.

The Supreme Court of India interpreted the scope of Article 23 by examining the working conditions of various individuals employed by Asiad projects. The petitioner in this case found that the workers were highly exploited, receiving wages below the minimum rate and enduring poor working conditions. The case was filed as a Public Interest Litigation (PIL).

Justice PN Bhagwati noted that Article 23 has a broad and unrestricted scope, it not only prohibits “begar” but also any forms of forced labor, regardless of its existence. According to the court, forced labor of any kind is not allowed.

The court emphasized that no one should be made to do labor or services against their will, even if it is specified in a service agreement. Under Article 23, the term “force” has a broad definition which includes situations where a person is forced to work against their will for less than minimum wage due to economic pressure or physical or legal pressure.

An organization called Bandhua Mukti Morcha fights against India’s widespread system of bonded labor. This case was unique because it was the first time that the court accepted a letter from J. Bhagwati as a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) petition. The letter outlined the suffering of numerous laborers who were subjected to unbearable and inhumane working conditions in the Faridabad region of Uttar Pradesh.

The court established guidelines for identifying bonded workers and made it clear that it was the responsibility of the state government to locate, free, and rehabilitate the bonded workers. This case highlights the efforts of the Bandhua Mukti Morcha organization to raise awareness and combat the problem of bonded labor in India, as well as the court’s recognition of the issue and its role in addressing it through the establishment of guidelines and allocation of responsibility to the state government.

In this case, the state had employed individuals for the construction of roads under the authority of the Famine Relief Act. However, it was argued that the workers were paid significantly less than the minimum wages, in violation of Article 23.

The court ruled that the state is not permitted to exploit the vulnerability of individuals under the guise of providing assistance during a famine or drought. The court recognized that these workers should be fairly compensated for their labor and the benefits it provides to the state.

The court noted that paying less than minimum wages to workers who are providing labor in times of famine or drought is not acceptable and that the state must ensure that the workers are paid fairly for the work they put in. This is a clear indication that the court believes in protecting the rights of the workers and ensuring that they are not exploited during vulnerable times.

The court ruled that if prisoners are made to perform labor without being paid fair wages, it constitutes a violation of Article 23 of the Constitution. This is because it impacts the dignity and freedom of individuals.

Furthermore, forcing prisoners to work without fair compensation is a form of exploitation, which is prohibited under Article 23. The court’s decision highlights the importance of ensuring that the rights of prisoners are protected and that they are not subjected to exploitative labor practices. Additionally, this decision is a reminder that everyone has the right to fair compensation for their labor, regardless of their circumstances.

In the case of Neerja Choudhary v. State of Madhya Pradesh, 1984, the Supreme Court of India established that when a worker is compelled to perform labor without fair compensation, it is presumed to be a case of bonded labor, unless the employer can prove otherwise. The Court also emphasized that the failure of the government to enforce the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976 would be a clear violation of Articles 21 and 23 of the Constitution which protect the right to life and personal liberty and the prohibition of traffic in human beings and forced labour respectively.

The court’s decision in this case emphasizes the importance of protecting the rights of workers and ensuring that they are not subjected to exploitative labor practices. The decision also highlights the government’s responsibility to enforce laws that protect workers and to hold employers accountable for any violations of these laws. Furthermore, the court’s decision emphasizes the importance of protecting the rights of workers and ensuring that they are not subjected to exploitative labor practices and the failure of government to enforce laws that protect workers is considered as violation of the rights of citizens.

Prohibition of employment of children in factories, etc. No child below the age of fourteen years shall be employed to work in any factory or mine or engaged in any other hazardous employment.

Article 24 of the Indian Constitution states that no child under the age of 14 years old shall be employed to work in any factory, mine, or engaged in any other type of hazardous employment. The article is aimed at protecting the rights of children and ensuring that they are not subjected to dangerous working conditions at a young age. The prohibition of child labor in hazardous environments is an important measure to safeguard the well-being and development of children and to prevent them from being exploited. The language of the article is clear, that is no child below the age of 14 should be employed in any factory or mine or in any other hazardous occupation.

The Supreme Court of India determined that construction work is a particularly dangerous job that should not be performed by anyone under the age of 14.

In addition, the court also highlighted the horizontal aspect of Article 24, which means that it applies to both the state and private individuals. This means that the prohibition against employing children under the age of 14 in hazardous occupations, as outlined in Article 24, applies not only to government entities but also to private individuals or organizations.

The court emphasized that the protection of children’s rights and safety is not limited to the actions of the state, but extends to the actions of private individuals and organizations as well.

The Supreme Court of India, in the case of M.C. Mehta v. State of Tamil Nadu in 1997, determined that it is illegal for children under the age of 14 to be employed in any industry or work environment deemed hazardous, including mines. The court established guidelines to safeguard the rights of children, including their economic, social, and humanitarian rights.

Furthermore, the court emphasized the importance of employers adhering to the regulations outlined in the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act of 1986, which prohibits the employment of children in certain hazardous occupations and regulates the working conditions of children in non-hazardous occupations.

The Supreme Court commanded the creation of a fund for the rehabilitation and welfare of child labourers, and required the employer to give each child a compensation of Rs. 20,000.

The Child Labor (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986 is a law in India that aims to combat child labor by prohibiting and regulating the employment of children. This law defines a child as a person under the age of 14. The act specifies which occupations and procedures children are prohibited from working in and where and how they may be employed. The law prohibits children from working in 13 specific occupations and 57 specific procedures, which are considered hazardous to their health and development.

This act is considered a significant step in protecting the rights and welfare of children in India.

The Child Labor (Prohibition and Regulation) Amendment Act of 2016 is a law in India that prohibits and regulates child labor.

The law specifically prohibits the employment of children under the age of 14 and prohibits individuals between the ages of 14 and 18 from working in hazardous activities or processes. This amendment has strengthened the penalties for breaking this law. Additionally, the Act allows for young people to work in a variety of household jobs and as artists.

This law was passed to further protect the rights and welfare of children in India, by prohibiting the employment of children in hazardous work and by empowering young people to work in safe and appropriate jobs.

In 2017, the government of India issued rules to establish a comprehensive and specific framework for preventing, prohibiting, rescuing and rehabilitating child and adolescent workers. These rules were designed to clarify concerns related to the employment of children in family businesses and to provide protection for child artists by defining their working hours and conditions.

The objective of these rules is to ensure that children are protected from exploitation and abuse in the workplace and to ensure that their rights are upheld. These rules provide a detailed guideline for the implementation of the Child Labor (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986, and the Child Labor (Prohibition and Regulation) Amendment Act, 2016, and are aimed at ensuring the welfare and protection of children in the country.

A civilized society should not allow or condone the exploitation of children through practices such as child labor. Despite laws being put in place to prevent it, such as those outlined in articles 23 and 24, the issue remains prevalent in countries like India where there are over 42.7 million uneducated children and 10 million child laborers.