27 Real Primary Research Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

Primary research is a type of academic research that involves collecting new and original data to conduct a study.

Examples of primary research include studies that collect data through interviews, questionnaires, original text analysis, observation, surveys, focus groups, case studies, and ethnography.

It is the opposite of secondary research which involves looking at existing data to identify trends or new insights. Both secondary and primary research are legitimate forms of academic research.

Primary Research Examples

1. interviews.

Interviews involve approaching relevant people and asking them questions to gather their thoughts and opinions on a topic. This can take the form of structured, semi-strutured, and unstructured interviews.

Structured interviews generally do not involve back-and-forth discussion between the researcher and the research participant, while semi-structured and unstructured interviews involve the interviewer asking follow-up questions to dig deeper and elicit more insights.

| Nurses’ experiences of deaths in hospital (Costello, 2006) | Interviews of nurses about the circumstances of patients’ deaths revealed nurses felt patients’ deaths were more satisfactorily managed when they had greater organizational control, but nurses tended to worry more about the workplace organization than the patients’ experiences as they died. |

| General practitioners’ engagement in end-of-life care (Deckx, 2016) | The study conducted semi-structured interviews with 15 Australian GPs to examine their approach to end-of-life care. GPs were found to be cognizant of their patients approaching end-of-life care, and adjusted care plans accordingly. However, in certain cases, this was not made explicit through discussion. |

| Older Persons’ Views on Important Values in Swedish Home Care Service (Olsen et al., 2022) | Semi-structured interviews of 16 people aged 74–90 who received home care service explored which values they would like to see fro home care services. They found that elders primarily wanted two things: to be supported as autonomous people, and as relational beings. |

2. Questionnaires and Surveys

Questionnaires are text-based interviews where a set of questions are written down by the researchers and sent to the research participants. The participants fill out the questionnaires and return them to the researcher.

The researcher then anonymizes the data and analyzes it by looking for trends and patterns across the dataset. They may do this manually or use research tools to find similarities and differences in the responses of the research participants.

A simple questionnaire can take the form of a Likert scale which involves asking a research participant to circle their opinion on a set of pre-determined responses (e.g. ‘Very Likely, Likely, Unlikely, Very Unlikely’). Other questionnaires require participants to write detailed paragraphs responding to questions which can then be analyzed.

One benefit of surveys over interviews is that it’s easier to gather large datasets.

| Nurses’ Experiences with Web-Based Learning (Atack & Rankin, 2022) | Questionnaires were given to nurses following an online education module to gather feedback on their experiences of online learning. Results showed both successes and challenges from learning online. |

| Teacher perceptions of using mobile phones in the classroom: Age matters! (O’Bannon & Thomas, 2014) | A 50-item survey of 1095 teachers was used to examine teachers’ perceptions of the use of phones in the classroom. The survey results showed that teachers over 50 tended to have significantly less support for phones in the classroom than teachers under 50. |

| Parents’ Perceptions of Their Involvement in Schooling (Erdener & Knoeppel, 2018) | 742 parents took questionnaire surveys to assess their levels of involvement in their children’s education. Parents’ education, income and age were gathered in the survey. The study found that family income is the most influential factor affecting parental involvement in education. |

3. Control Group Analysis

Control group analyses involve separating research participants into two groups: the control group and the experimental group.

An intervention is applied to the experimental group. Researchers then observe the results and compare them to the control group to find out the effects of the intervention.

This sort of research is very common in medical research. For example, a new pill on the market might be used on two groups of sick patients to see whether the pill was effective in improving one group’s condition. If so, it may receive approval to go into the market.

| Comparison of Weight-Loss Diets with Different Compositions of Fat, Protein, and Carbohydrates (Sacks et al., 2009) | In this study, 811 overweight adults were assigned to one of four diets that varied in the percentages of fat, protein, and carbohydrates they contained. By the end of the two-year study, the participants assigned to the different diets had similar weight loss, with an average of 4 kg lost. |

| Effect of Low-Fat vs Low-Carbohydrate Diet on 12-Month Weight Loss in Overweight Adults (Gardner et al., 2018) | In this study, researchers randomized 609 overweight adults into two groups and assigned them to either a high-fat, low-carbohydrate (HLF) diet or a high-carbohydrate, low-fat (HLC) diet. The researchers found that the participants in both groups had similar weight loss after 12 months, with no significant difference between the two groups. This suggests that the HLF and HLC diets had similar effects on weight loss. |

| Calorie Restriction with or without Time-Restricted Eating in Weight Loss (Liu et al., 2022) | The researchers randomly assigned 139 patients with obesity to time-restricted eating or daily calorie restriction alone. At 12 months, the time-restriction group had a mean weight loss of 8kg and the daily-calorie-restriction group had a mean weight loss of −6.3 kg. However, the researchers found that this was not a significant enough difference to find value in one method over the other. |

4. Observation Studies

Observational studies involve the researchers entering a research setting and recording their naturalistic observations of what they see. These observations can then form the basis of a thesis.

Longer-term observation studies where the researcher is embedded in a community are called ethnographic studies.

Tools for observation studies include simple pen-and-paper written vignettes about a topic, recording with the consent of research participants, or using field measuring devices.

Observational studies in fields like anthropology can lead to rich and detailed explanations of complex phenomena through a process called thick description . However, they’re inherently qualitative, subjective , and small-case studies that often make it difficult to make future predictions or hard scientific findings.

Another research limitation is that the presence of the researcher can sometimes affect the behavior of the people or animals being observed.

| Putting “structure within the space”: Spatially un/responsive pedagogic practices (Saltmarsh et al., 2014) | The researchers observed interactions between students, teachers, and resources in an open learning classroom. Findings indicated that the layout of the classroom had a genuine impact on pedagogical practices, but factors such as teaching philosophies and student learning preferences also played a role in the spaces. |

| Musical expression: an observational study of instrumental teaching (Karlsson & Juslin, 2008) | Music lessons among a cohort of five teachers were filmed, transcribed, and thematized. Results demonstrated that the music lessons tended to be teacher-centered and lacked clear goals. This small-scale study may have been beneficial in a qualitative and contextualized way, but not useful in providing generalized knowledge for furthering research into musical pedagogy. |

| Writing instruction in first grade: an observational study (Coker et al., 2016) | Daylong observations in 50 first-grade classrooms found that explicit writing classes were taught for less than an average of 30 minutes per day. However, a high degree of variability in instructional methods and time demonstrated that first-grade writing instruction is inconsistently applied across schools which may cause high variations in the quality of writing instruction in US schools. |

Go Deeper: 15 Ethnography Examples

5. Focus Groups

Focus groups are similar to interviews, but involve small groups of research participants interacting with the interviewer and, sometimes, one another.

Focus group research is common, for example, in political research, where political parties commission independent research organizations to collect data about the electorate’s perceptions of the candidates. This can help inform them of how to more effectively position the candidate in advertising and press stops.

The biggest benefit of focus group studies is that they can gather qualitative information from a wider range of research participants than one-to-one interviews. However, the downside is that research participants tend to influence each others’ responses.

| Understanding Weight Stigmatization: A Focus Group Study (Cossrow, Jeffery & McGuire, 2001) | In a series of focus groups, research participants discussed their experiences with weight stigmatization and shared personal stories of being treated poorly because of their weight. The women in the focus groups reported a greater number and variety of negative experiences than the men. |

| Maternal Feeding Practices and Childhood Obesity (Baughcum et al, 1998) | This study was designed to identify maternal beliefs about child feeding that are associated with childhood obesity. The focus groups with mothers found that the mothers considered weight to be a direct measure of child health and parent confidence, which according to the resesarchers is too simplistic a perception, meaning physicians should be more careful in their language when working with mothers. |

| Exploring university students’ perceptions of plagiarism: a focus group study (Gullifer & Tyson, 2010) | Focus groups with university students about their knowledge and understanding of plagiarism found six themes: confusion, fear, , perceived seriousness, academic consequences and resentment. |

See More: Examples of Focus Groups

6. Online Surveys

Online surveys are similar in purpose to offline questionnaires and surveys, but have unique benefits and limitations.

Like offline surveys and questionnaires, they can be in the form of written responses, multiple choice, and Likert scales.

However, they have some key benefits including: capacity to cast a wide net, ease of snowball sampling, and ease of finding participants.

These strengths also present some potential weaknesses: poorly designed online surveys may be corrupted if the sample is not sufficiently vetted and only distributed to non-representative sample sets (of course, this can be offset, depending on the study design).

| EU Kids Online 2020 (Smahel et al, 2020) | A survey of children’s internet use (aged 9–16) across 19 European nations. 25,101 children conducted online surveys. Findings showed girls accessed the internet using smartphones more than boys. |

| Use of Smartphone Apps, Social Media, and Web-Based Resources to Support Mental Health and Well-Being (Stawarz, Preist & Coyle, 2019) | A survey of 81 people who use technology to support their mental health, finding that participants found mental health apps to be useful but not sufficient to replace face-to-face therapy. |

| Student Perceptions on the Importance of Engagement Strategies in the Online Learning Environment (Martin & Bollinger, 2018) | 155 students conducted an online survey with 38 items on it that assessed perceptions of engagement starategies used in online classes. It found that email reminders and regular announcements were the most effective engagement strategies. |

7. Action Research

Action research involves practitioners conducting just-in-time research in an authentic setting to improve their own practice. The researcher is an active participant who studies the effects of interventions.

It sits in contrast to other forms of primary research in this list, which are mostly conducted by researchers who attempt to detach themselves from the subject of study. Action research, on the other hand, involves a researcher who is also a participant.

Action research is most commonly used in classrooms, where teachers take the role of researchers to improve their own teaching and learning practices. However, action research can be used in other fields as well, particularly healthcare and social work.

| Instructional technology adoption in higher education (Groves & Zemel, 2000) | The practitioner-researschers looked at how they and their teaching assistants used technology in their teaching. The results showed that in order to incorporate technology in their teaching, they needed more accessible hardware, training, and discipline-specific media that was easy to use. |

| An action research project: Student perspectives on small-group learning in chemistry (Towns, Kreke & Fields 2000) | The authors used action research cycles – where they taught lessons, gathered evidence, reflected, created new and improved lessons based on their findings, and repeated the process. Their focus was on improving small-group learning. |

| Task-based language learning and teaching: An action-research study (Calvert & Sheen, 2014) | This action research study involved a teacher who developed and implemented a language learning task for adult refugees in an English program. The teacher critically reflected on and modified the task to better suit the needs of her students. |

Go Deeper: 21 Action Research Examples

8. Discourse and Textual Analysis

Discourse and textual analyses are studies of language and text. They could involve, for example, the collection of a selection of newspaper articles published within a defined timeframe to identify the ideological leanings of the newspapers.

This sort of analysis can also explore the language use of media to study how media constructs stereotypes. The quintessential example is the study of gender identities is Disney texts, which has historically shown how Disney texts promote and normalize gender roles that children could internalize.

Textual analysis is often confused as a type of secondary research. However, as long as the texts are primary sources examined from scratch, it should be considered primary research and not the analysis of an existing dataset.

| The Chronic Responsibility: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Danish Chronic Care Policies (Ravn, Frederiksen & Beedholm, 2015) | The authors examined Danish chronic care policy documents with a focus on how they categorize and pathologize vulnerable patients. |

| House price inflation in the news: a critical discourse analysis of newspaper coverage in the UK (Munro, 2018) | The study looks at how newspapers report on housing price rises in the UK. It shows how language like “natural” and “healthy” normalizes ever-rising housing prices and aims to dispel alternative discourses around ensuring access to the housing market for the working class. |

| Critical discourse analysis in political communication research: a case study of rightwing populist discourse in Australia (Sengul, 2019) | This author highlights the role of political speech in constructing a singular national identity that attempts to delineate in-groups and out-groups that marginalize people within a multicultural nation. |

Go Deeper: 21 Discourse Analysis Examples

9. Multimodal, Visual, and Semiotic Analysis

Discourse and textual analyses traditionally focused on words and written text. But with the increasing presence of visual texts in our lives, scholars had to come up with primary research studies that involved the analysis of multimodal texts .

This led to studies such as semiotics and multimodal discourse analysis. This is still considered primary research because it involves the direct analysis of primary data (such as pictures, posters, and movies).

While these studies tend to borrow significantly from written text analysis, they include methods such as social semiotic to explore how signs and symbols garner meaning in social contexts. This enables scholars to examine, for example, children’s drawings through to famous artworks.

| Exploring children’s perceptions of scientists through drawings and interviews (Samaras, Bonoti & Christidou, 2012) | These researchers analyzed children’s drawings of scientists and examined the presence of ‘indicators’ of stereotypes such as lab coats, eyeglasses, facial hair, research symbols, and so on. The study found the drawings were somewhat traditionally gendered. Follow-up interviews showed the children had less gender normative views of scientists, showing how mixed-methods research can be valuable for elucidating deeper insights. |

| Elitism for sale: Promoting the elite school online in the competitive educational marketplace (Drew, 2013) | A multimodal analysis of elite school websites, demonstrating how they use visual and audible markers of elitism, wealth, tradition, and exclusivity to market their products. Examples include anachronistic uniforms and low-angle shots of sandstone buildings that signify opulence and social status that can be bought through attendance in the institutions. |

| A social semiotic analysis of gender power in Nigeria’s newspaper political cartoons (Felicia, 2021) | A study of political cartoons in Norwegian newspapers that requires visual and semiotic analysis to gather meaning from the original text. The study collects a corpus of cartoons then contextualizes the cultural symbology to find that framing, salience in images, and visual metaphors create and reproduce Nigerian metanarratives of gender. |

Often, primary research is a more highly-regarded type of research than secondary research because it involves gathering new data.

However, secondary research should not be discounted: the synthesis, categorization, and critique of an existing corpus of research can reveal excellent new insights and help to consolidate academic knowledge and even challenge longstanding assumptions .

References for the mentioned studies (APA Style)

Atack, L., & Rankin, J. (2002). A descriptive study of registered nurses’ experiences with web‐based learning. Journal of Advanced Nursing , 40 (4), 457-465.

Baughcum, A. E., Burklow, K. A., Deeks, C. M., Powers, S. W., & Whitaker, R. C. (1998). Maternal feeding practices and childhood obesity: a focus group study of low-income mothers. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine , 152 (10), 1010-1014.

Calvert, M., & Sheen, Y. (2015). Task-based language learning and teaching: An action-research study. Language Teaching Research , 19 (2), 226-244.

Coker, D. L., Farley-Ripple, E., Jackson, A. F., Wen, H., MacArthur, C. A., & Jennings, A. S. (2016). Writing instruction in first grade: An observational study. Reading and Writing , 29 (5), 793-832.

Cossrow, N. H., Jeffery, R. W., & McGuire, M. T. (2001). Understanding weight stigmatization: A focus group study. Journal of nutrition education , 33 (4), 208-214.

Costello, J. (2006). Dying well: nurses’ experiences of ‘good and bad’deaths in hospital. Journal of advanced nursing , 54 (5), 594-601.

Deckx, L., Mitchell, G., Rosenberg, J., Kelly, M., Carmont, S. A., & Yates, P. (2019). General practitioners’ engagement in end-of-life care: a semi-structured interview study. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care .

Drew, C. (2013). Elitism for sale: Promoting the elite school online in the competitive educational marketplace. Australian Journal of Education , 57 (2), 174-184.

Erdener, M. A., & Knoeppel, R. C. (2018). Parents’ Perceptions of Their Involvement in Schooling. International Journal of Research in Education and Science , 4 (1), 1-13.

Felicia, O. (2021). A social semiotic analysis of gender power in Nigeria’s newspaper political cartoons. Social Semiotics , 31 (2), 266-281.

Gardner, C. D., Trepanowski, J. F., Del Gobbo, L. C., Hauser, M. E., Rigdon, J., Ioannidis, J. P., … & King, A. C. (2018). Effect of low-fat vs low-carbohydrate diet on 12-month weight loss in overweight adults and the association with genotype pattern or insulin secretion: the DIETFITS randomized clinical trial. Jama , 319 (7), 667-679.

Groves, M. M., & Zemel, P. C. (2000). Instructional technology adoption in higher education: An action research case study. International Journal of Instructional Media , 27 (1), 57.

Gullifer, J., & Tyson, G. A. (2010). Exploring university students’ perceptions of plagiarism: A focus group study. Studies in Higher Education , 35 (4), 463-481.

Karlsson, J., & Juslin, P. N. (2008). Musical expression: An observational study of instrumental teaching. Psychology of music , 36 (3), 309-334.

Liu, D., Huang, Y., Huang, C., Yang, S., Wei, X., Zhang, P., … & Zhang, H. (2022). Calorie restriction with or without time-restricted eating in weight loss. New England Journal of Medicine , 386 (16), 1495-1504.

Martin, F., & Bolliger, D. U. (2018). Engagement matters: Student perceptions on the importance of engagement strategies in the online learning environment. Online Learning , 22 (1), 205-222.

Munro, M. (2018). House price inflation in the news: a critical discourse analysis of newspaper coverage in the UK. Housing Studies , 33 (7), 1085-1105.

O’bannon, B. W., & Thomas, K. (2014). Teacher perceptions of using mobile phones in the classroom: Age matters!. Computers & Education , 74 , 15-25.

Olsen, M., Udo, C., Dahlberg, L., & Boström, A. M. (2022). Older Persons’ Views on Important Values in Swedish Home Care Service: A Semi-Structured Interview Study. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare , 15 , 967.

Ravn, I. M., Frederiksen, K., & Beedholm, K. (2016). The chronic responsibility: a critical discourse analysis of Danish chronic care policies. Qualitative Health Research , 26 (4), 545-554.

Sacks, F. M., Bray, G. A., Carey, V. J., Smith, S. R., Ryan, D. H., Anton, S. D., … & Williamson, D. A. (2009). Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. New England Journal of Medicine , 360 (9), 859-873.

Saltmarsh, S., Chapman, A., Campbell, M., & Drew, C. (2015). Putting “structure within the space”: Spatially un/responsive pedagogic practices in open-plan learning environments. Educational Review , 67 (3), 315-327.

Samaras, G., Bonoti, F., & Christidou, V. (2012). Exploring children’s perceptions of scientists through drawings and interviews. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences , 46 , 1541-1546.

Sengul, K. (2019). Critical discourse analysis in political communication research: a case study of right-wing populist discourse in Australia. Communication Research and Practice , 5 (4), 376-392.

Smahel, D., Machackova, H., Mascheroni, G., Dedkova, L., Staksrud, E., Ólafsson, K., … & Hasebrink, U. (2020). EU Kids Online 2020: Survey results from 19 countries.

Stawarz, K., Preist, C., & Coyle, D. (2019). Use of smartphone apps, social media, and web-based resources to support mental health and well-being: online survey. JMIR mental health , 6 (7), e12546.Towns, M. H., Kreke, K., & Fields, A. (2000). An action research project: Student perspectives on small-group learning in chemistry. Journal of Chemical Education , 77 (1), 111.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Writing Center

- Current Students

- Online Only Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Parents & Family

- Alumni & Friends

- Community & Business

- Student Life

- Video Introduction

- Become a Writing Assistant

- All Writers

- Graduate Students

- ELL Students

- Campus and Community

- Testimonials

- Encouraging Writing Center Use

- Incentives and Requirements

- Open Educational Resources

- How We Help

- Get to Know Us

- Conversation Partners Program

- Weekly Updates

- Workshop Series

- Professors Talk Writing

- Computer Lab

- Starting a Writing Center

- A Note to Instructors

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review

- Research Proposal

- Argument Essay

- Rhetorical Analysis

Introduction to Primary Research: Observations, Surveys, and Interviews

Primary Research: Definitions and Overview

How research is defined varies widely from field to field, and as you progress through your college career, your coursework will teach you much more about what it means to be a researcher within your field.* For example, engineers, who focus on applying scientific knowledge to develop designs, processes, and objects, conduct research using simulations, mathematical models, and a variety of tests to see how well their designs work. Sociologists conduct research using surveys, interviews, observations, and statistical analysis to better understand people, societies, and cultures. Graphic designers conduct research through locating images for reference for their artwork and engaging in background research on clients and companies to best serve their needs. Historians conduct research by examining archival materials—newspapers, journals, letters, and other surviving texts—and through conducting oral history interviews. Research is not limited to what has already been written or found at the library, also known as secondary research. Rather, individuals conducting research are producing the articles and reports found in a library database or in a book. Primary research, the focus of this essay, is research that is collected firsthand rather than found in a book, database, or journal.

Primary research is often based on principles of the scientific method, a theory of investigation first developed by John Stuart Mill in the nineteenth century in his book Philosophy of the Scientific Method . Although the application of the scientific method varies from field to field, the general principles of the scientific method allow researchers to learn more about the world and observable phenomena. Using the scientific method, researchers develop research questions or hypotheses and collect data on events, objects, or people that is measurable, observable, and replicable. The ultimate goal in conducting primary research is to learn about something new that can be confirmed by others and to eliminate our own biases in the process.

Essay Overview and Student Examples

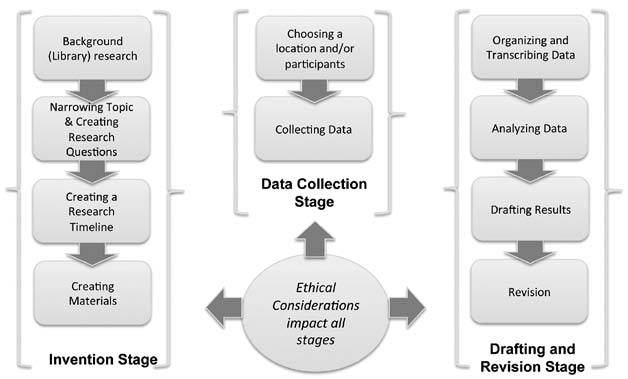

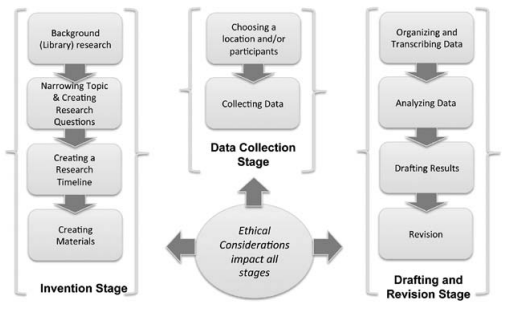

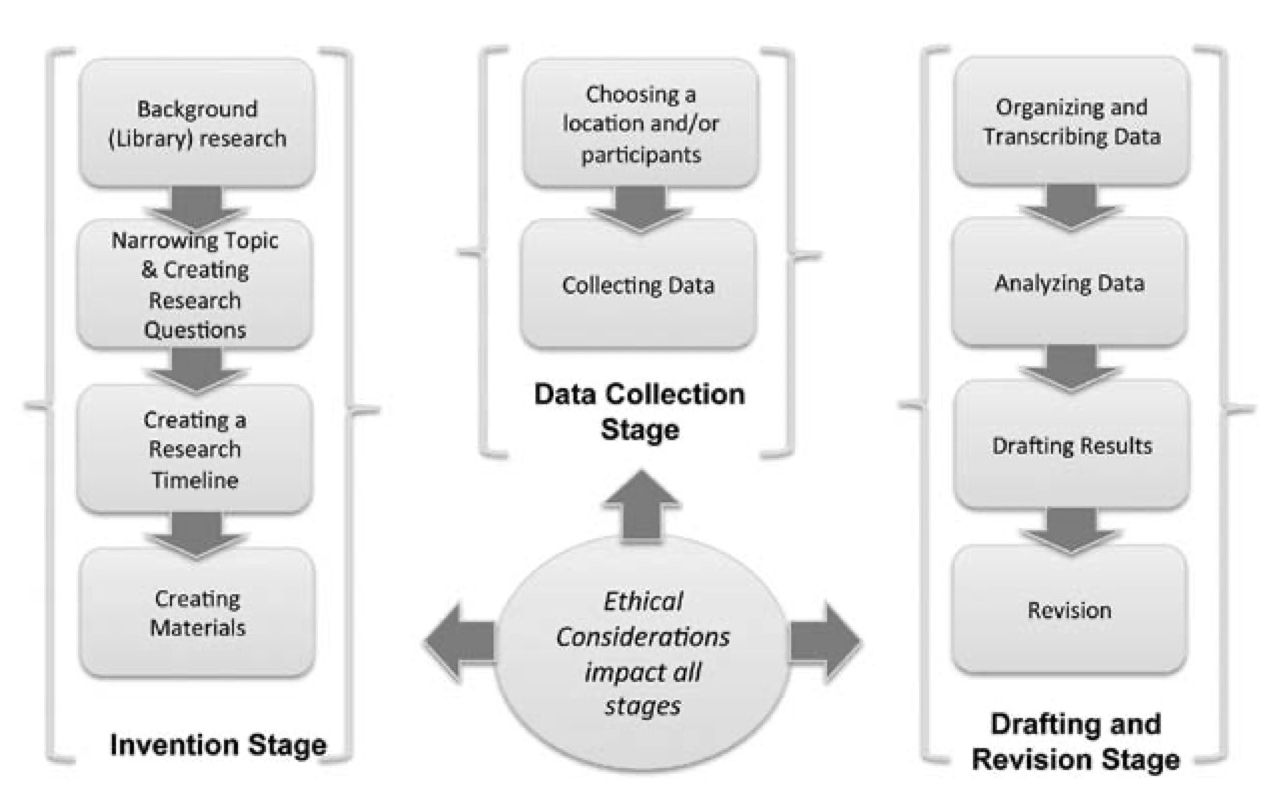

The essay begins by providing an overview of ethical considerations when conducting primary research, and then covers the stages that you will go through in your primary research: planning, collecting, analyzing, and writing. After the four stages comes an introduction to three common ways of conducting primary research in first year writing classes:

Observations . Observing and measuring the world around you, including observations of people and other measurable events.

Interviews . Asking participants questions in a one-on-one or small group setting.

Surveys . Asking participants about their opinions and behaviors through a short questionnaire.

In addition, we will be examining two student projects that used substantial portions of primary research:

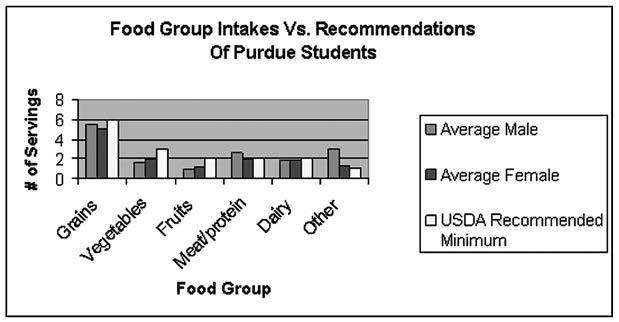

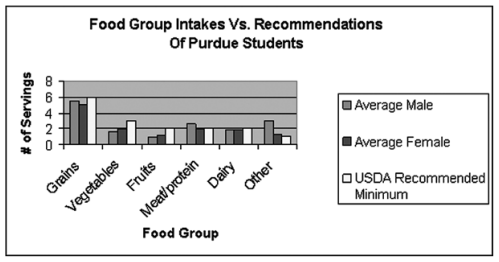

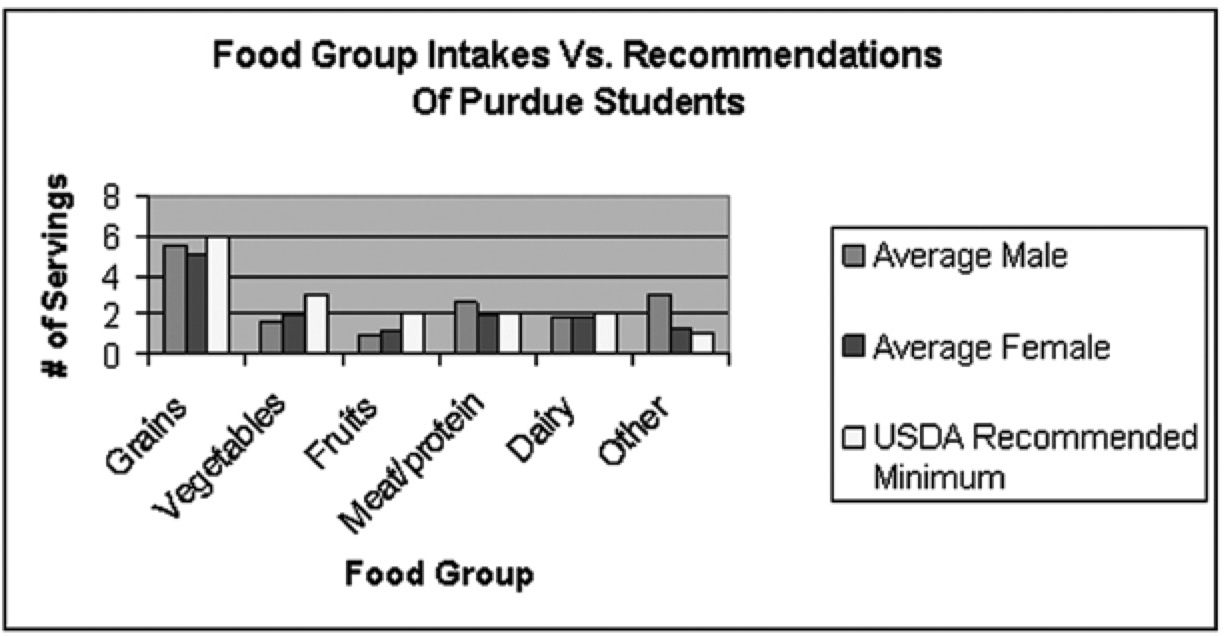

Derek Laan, a nutrition major at Purdue University, wanted to learn more about student eating habits on campus. His primary re-search included observations of the campus food courts, student behavior while in the food courts, and a survey of students’ daily food intake. His secondary research included looking at national student eating trends on college campuses, information from the United States Food and Drug Administration, and books on healthy eating.

Jared Schwab, an agricultural and biological engineering major at Purdue, was interested in learning more about how writing and communication took place in his field. His primary research included interviewing a professional engineer and a student who was a senior majoring in engineering. His secondary research included examining journals, books, professional organizations, and writing guides within the field of engineering.

Ethics of Primary Research

Both projects listed above included primary research on human participants; therefore, Derek and Jared both had to consider research ethics throughout their primary research process. As Earl Babbie writes in The Practice of Social Research , throughout the early and middle parts of the twentieth century researchers took advantage of participants and treated them unethically. During World War II, Nazi doctors performed heinous experiments on prisoners without their consent, while in the U.S., a number of medical and psychological experiments on caused patients undue mental and physical trauma and, in some cases, death. Because of these and other similar events, many nations have established ethical laws and guidelines for researchers who work with human participants. In the United States, the guidelines for the ethical treatment of human research participants are described in The Belmont Report , released in 1979. Today, universities have Institutional Review Boards (or IRBs) that oversee research. Students conducting research as part of a class may not need permission from the university’s IRB, although they still need to ensure that they follow ethical guidelines in research. The following provides a brief overview of ethical considerations:

- Voluntary participation . The Belmont Report suggests that, in most cases, you need to get permission from people before you involve them in any primary research you are conducting. If you are doing a survey or interview, your participants must first agree to fill out your survey or to be interviewed. Consent for observations can be more complicated, and is dis-cussed later in the essay.

Confidentiality and anonymity . Your participants may reveal embarrassing or potentially damaging information such as racist comments or unconventional behavior. In these cases, you should keep your participants’ identities anonymous when writing your results. An easy way to do this is to create a “pseudonym” (or false name) for them so that their identity is protected.

Researcher bias . There is little point in collecting data and learning about something if you already think you know the answer! Bias might be present in the way you ask questions, the way you take notes, or the conclusions you draw from the data you collect.

The above are only three of many considerations when involving human participants in your primary research. For a complete under-standing of ethical considerations please refer to The Belmont Report .

Now that we have considered the ethical implications of research, we will examine how to formulate research questions and plan your primary research project.

Planning Your Primary Research Project

The primary research process is quite similar to the writing process, and you can draw upon your knowledge of the writing process to understand the steps involved in a primary research project. Just like in the writing process, a successful primary research project begins with careful planning and background research. This section first describes how to create a research timeline to help plan your research. It then walks you through the planning stages by examining when primary research is useful or appropriate for your first year composition course, narrowing down a topic, and developing research questions.

The Research Timeline

When you begin to conduct any kind of primary research, creating a timeline will help keep you on task. Because students conducting primary research usually focus on the collection of data itself, they often overlook the equally important areas of planning (invention), analyzing data, and writing. To help manage your time, you should create a research timeline, such as the sample timeline presented here.

When Primary Research Is Useful or Appropriate

In Evaluating Scientific Research: Separating Fact from Fiction , Fred Leavitt explains that primary research is useful for questions that can be answered through asking others and direct observation. For first year writing courses, primary research is particularly useful when you want to learn about a problem that does not have a wealth of published information. This may be because the problem is a recent event or it is something not commonly studied. For example, if you are writing a paper on a new political issue, such as changes in tax laws or healthcare, you might not be able to find a wealth of peer-reviewed research because the issue is only several weeks old. You may find it necessary to collect some of your own data on the issue to supplement what you found at the library. Primary research is also useful when you are studying a local problem or learning how a larger issue plays out at the local level. Although you might be able to find information on national statistics for healthy eating, whether or not those statistics are representative of your college campus is something that you can learn through primary research.

However, not all research questions and topics are appropriate for primary research. As Fred Leavitt writes, questions of an ethical, philosophical, or metaphysical nature are not appropriate because these questions are not testable or observable. For example, the question “Does an afterlife exist?” is not a question that can be answered with primary research. However, the question “How many people in my community believe in an afterlife?” is something that primary research can answer.

Narrowing Your Topic

Just like the writing process, you should start your primary research process with secondary (library) research to learn more about what is already known and what gaps you need to fill with your own data. As you learn more about the topic, you can narrow down your interest area and eventually develop a research question or hypothesis, just as you would with a secondary research paper.

Developing Research Questions or Hypotheses

As John Stuart Mill describes, primary research can use both inductive and deductive approaches, and the type approach is usually based on the field of inquiry. Some fields use deductive reasoning , where researchers start with a hypothesis or general conclusion and then collect specific data to support or refute their hypothesis. Other fields use inductive reasoning , where researchers start with a question and collect information that eventually leads to a conclusion.

Once you have spent some time reviewing the secondary research on your topic, you are ready to write a primary research question or hypothesis. A research question or hypothesis should be something that is specific, narrow, and discoverable through primary research methods. Just like a thesis statement for a paper, if your research question or hypothesis is too broad, your research will be unfocused and your data will be difficult to analyze and write about. Here is a set of sample research questions:

Poor Research Question : What do college students think of politics and the economy?

Revised Research Question : What do students at Purdue University believe about the current economic crisis in terms of economic recoverability?

The poor research question is unspecific as to what group of students the researcher is interested in—i.e. students in the U.S.? In a particular state? At their university? The poor research question was also too broad; terms like “politics” and the “economy” cover too much ground for a single project. The revised question narrows down the topic to students at a particular university and focuses on a specific issue related to the economy: economic recoverability. The research question could also be rephrased as a testable hypothesis using deductive reasoning: “Purdue University college students are well informed about economic recoverability plans.” Because they were approaching their projects in an exploratory, inductive manner, both Derek and Jared chose to ask research questions:

Derek: Are students’ eating habits at Purdue University healthy or unhealthy? What are the causes of students’ eating behavior?

Jared: What are the major features of writing and communication in agricultural and biological engineering? What are the major controversies?

A final step in working with a research question or hypothesis is determining what key terms you are using and how you will define them. Before conducting his research, Derek had to define the terms “healthy” and “unhealthy”; for this, he used the USDA’s Food Pyramid as a guide. Similarly, part of what Jared focused on in his interviews was learning more about how agricultural and biological engineers defined terms like “writing” and “communication.” Derek and Jared thought carefully about the terms within their research questions and how these terms might be measured.

Choosing a Data Collection Method

Once you have formulated a research question or hypothesis, you will need to make decisions about what kind of data you can collect that will best address your research topic. Derek chose to examine eating habits by observing both what students ate at lunch and surveying students about eating behavior. Jared decided that in-depth interviews with experienced individuals in his field would provide him with the best information.

To choose a data collection method for your research question, read through the next sections on observations, interviews, and surveys.

Observations

Observations have lead to some of the most important scientific discoveries in human history. Charles Darwin used observations of the animal and marine life at the Galapagos Islands to help him formulate his theory of evolution that he describes in On the Origin of Species . Today, social scientists, natural scientists, engineers, computer scientists, educational researchers, and many others use observations as a primary research method.

Observations can be conducted on nearly any subject matter, and the kinds of observations you will do depend on your research question. You might observe traffic or parking patterns on campus to get a sense of what improvements could be made. You might observe clouds, plants, or other natural phenomena. If you choose to observe people, you will have several additional considerations including the manner in which you will observe them and gain their consent.

If you are observing people, you can choose between two common ways to observe: participant observation and unobtrusive observation. Participant observation is a common method within ethnographic research in sociology and anthropology. In this kind of observation, a researcher may interact with participants and become part of their community. Margaret Mead, a famous anthropologist, spent extended periods of time living in, and interacting with, communities that she studied. Conversely, in unobtrusive observation, you do not interact with participants but rather simply record their behavior. Although in most circumstances people must volunteer to be participants in research, in some cases it is acceptable to not let participants know you are observing them. In places that people perceive as public, such as a campus food court or a shopping mall, people do not expect privacy, and so it is generally acceptable to observe without participant consent. In places that people perceive as private, which can include a church, home, classroom, or even an intimate conversation at a restaurant, participant consent should be sought.

The second issue about participant consent in terms of unobtrusive observation is whether or not getting consent is feasible for the study. If you are observing people in a busy airport, bus station, or campus food court, getting participant consent may be next to impossible. In Derek’s study of student eating habits on campus, he went to the campus food courts during meal times and observed students purchasing food. Obtaining participant consent for his observations would have been next to impossible because hundreds of students were coming through the food court during meal times. Since Derek’s research was in a place that participants would perceive as public, it was not practical to get their consent, and since his data was anonymous, he did not violate their privacy.

Eliminating Bias in Your Observation Notes

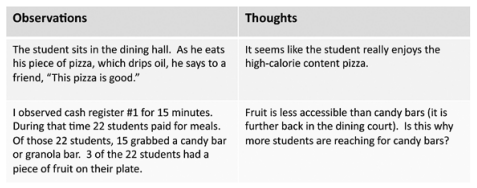

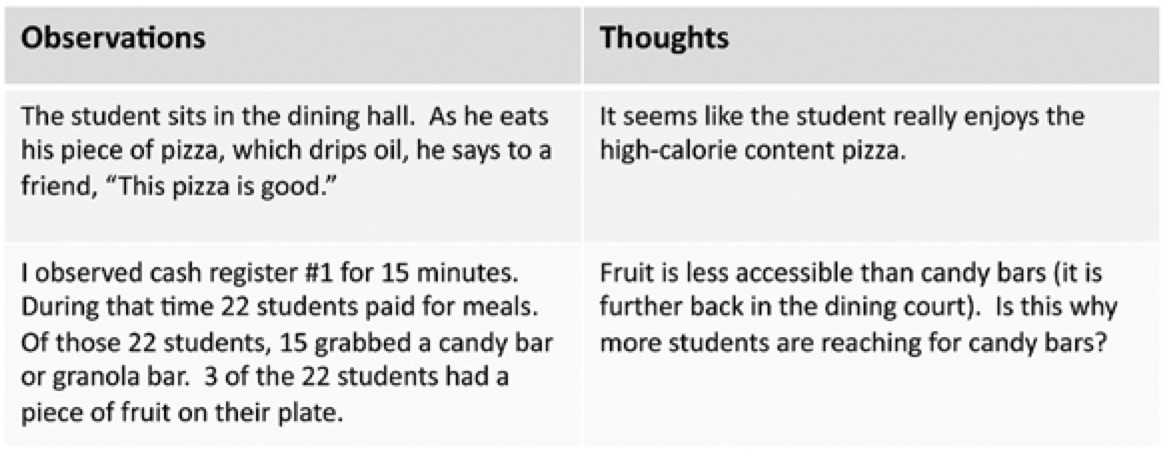

The ethical concern of being unbiased is important in recording your observations. You need to be aware of the difference between an observation (recording exactly what you see) and an interpretation (making assumptions and judgments about what you see). When you observe, you should focus first on only the events that are directly observable. Consider the following two example entries in an observation log:

- The student sitting in the dining hall enjoys his greasy, oil-soaked pizza. He is clearly oblivious of the calorie content and damage it may do to his body.

- The student sits in the dining hall. As he eats his piece of pizza, which drips oil, he says to a friend, “This pizza is good.”

The first entry is biased and demonstrates judgment about the event. First, the observer makes assumptions about the internal state of the student when she writes “enjoys” and “clearly oblivious to the calorie content.” From an observer’s standpoint, there is no way of ascertaining what the student may or may not know about pizza’s nutritional value nor how much the student enjoys the pizza. The second entry provides only the details and facts that are observable.

To avoid bias in your observations, you can use something called a “double-entry notebook.” This is a type of observation log that encourages you to separate your observations (the facts) from your feelings and judgments about the facts.

- Observations Thoughts

- The student sits in the dining hall. As he eats his piece of pizza, which drips oil, he says to a friend, "this pizza is good." It seems like the student really enjoys the high-calorie-content pizza.

- I observed cash register #1 for 15 minutes. During that time, 22 students paid for meals. Of those 22 students, 15 grabbed a candy bar or granola bar. 3 of the 22 students had a piece of fruit on their plate Fruit is less accessible than candy bars (it is further back in the dining court). Is this why more students are reaching for candy bars?

Figure 3: Two sample entries from a double-entry notebook.

Observations are only one strategy in collecting primary research. You may also want to ask people directly about their behaviors, beliefs, or attitudes—and for this you will need to use surveys or interviews.

Surveys and Interviews: Question Creation

Sometimes it is very difficult for a researcher to gain all of the necessary information through observations alone. Along with his observations of the dining halls, Derek wanted to know what students ate in a typical day, and so he used a survey to have them keep track of their eating habits. Likewise, Jared wanted to learn about writing and communication in engineering and decided to draw upon expert knowledge by asking experienced individuals within the field.

Interviews and surveys are two ways that you can gather information about people’s beliefs or behaviors. With these methods, the information you collect is not first-hand (like an observation) but rather “self-reported” data, or data collected in an indirect manner. William Shadish, Thomas Cook, and Donald Campbell argued that people are inherently biased about how they see the world and may report their own actions in a more favorable way than they may actually behave. Despite the issues in self-reported data, surveys and interviews are an excellent way to gather data for your primary research project.

Survey or Interview?

How do you choose between conducting a survey or an interview? It depends on what kind of information you are looking for. You should use surveys if you want to learn about a general trend in people’s opinions, experiences, and behavior. Surveys are particularly useful to find small amounts of information from a wider selection of people in the hopes of making a general claim. Interviews are best used when you want to learn detailed information from a few specific people. Interviews are also particularly useful if you want to interview experts about their opinions, as Jared did. In sum, use interviews to gain de-tails from a few people, and surveys to learn general patterns from many people.

Writing Good Questions

One of the greatest challenges in conducting surveys and interviews is writing good questions. As a researcher, you are always trying to eliminate bias, and the questions you ask need to be unbiased and clear. Here are some suggestions on writing good questions:

Ask about One Thing at a Time

A poorly written question can contain multiple questions, which can confuse participants or lead them to answer only part of the question you are asking. This is called a “double-barreled question” in journalism. The following questions are taken from Jared’s research:

Poor question: What kinds of problems are being faced in the field today and where do you see the search for solutions to these problems going?

Revised question #1: What kinds of problems are being faced in the field today?

Revised question #2: Where do you see the search for solutions to these problems going?

Avoid Leading Questions

A leading question is one where you prompt the participant to respond in a particular way, which can create bias in the answers given:

Leading question: The economy is clearly in a crisis, wouldn’t you agree?

Revised question: Do you believe the economy is currently in a crisis? Why or why not?

Understand When to Use Open and Closed Questions

Closed questions, or questions that have yes/no or other limited responses, should be used in surveys. However, avoid these kinds of questions in interviews because they discourage the interviewee from going into depth. The question sample above, “Do you believe the economy currently is in a crisis?” could be answered with a simple yes or no, which could keep a participant from talking more about the issue. The “why or why not?” portion of the question asks the participant to elaborate. On a survey, the question “Do you believe the economy currently is in a crisis?” is a useful question because you can easily count the number of yes and no answers and make a general claim about participant responses.

Write Clear Questions

When you write questions, make sure they are clear, concise, and to the point. Questions that are too long, use unfamiliar vocabulary, or are unclear may confuse participants and you will not get quality responses.

Now that question creation has been addressed, we will next examine specific considerations for interviews and surveys.

Interviews, or question and answer sessions with one or more people, are an excellent way to learn in-depth information from a person for your primary research project. This section presents information on how to conduct a successful interview, including choosing the right person, ways of interviewing, recording your interview, interview locations, and transcribing your interview.

Choosing the Right Person

One of the keys to a successful interview is choosing the right person to interview. Think about whom you would like to interview and whom you might know. Do not be afraid to ask people you do not know for interviews. When asking, simply tell them what the interview will be about, what the interview is for, and how much time it will take. Jared used his Purdue University connection to locate both of the individuals that he ended up interviewing—an advanced Purdue student and a Purdue alum working in an Engineering firm.

Face-to-Face and Virtual Interviews

When interviewing, you have a choice of conducting a traditional, face-to-face interview or an interview using technology over the Internet. Face-to-face interviews have the strength that you can ask follow-up questions and use non-verbal communication to your advantage. Individuals are able to say much more in a face-to-face interview than in an email, so you will get more information from a face-to-face interview. However, the Internet provides a host of new possibilities when it comes to interviewing people at a distance. You may choose to do an email interview, where you send questions and ask the person to respond. You may also choose to use a video or audio conferencing program to talk with the person virtually. If you are choosing any Internet-based option, make sure you have a way of recording the interview. You may also use a chat or instant messaging program to interview your participant—the benefit of this is that you can ask follow-up questions during the interview and the interview is already transcribed for you. Because one of his interviewees lived several hours away, Jared chose to interview the Purdue student face-to-face and the Purdue alum via email.

Finding a Suitable Location

If you are conducting an in-person interview, it is essential that you find a quiet place for your interview. Many universities have quiet study rooms that can be reserved (often found in the university library). Do not try to interview someone in a coffee shop, dining hall, or other loud area, as it is difficult to focus and get a clear recording.

Recording Interviews

One way of eliminating bias in your research is to record your interviews rather than rely on your memory. Recording interviews allows you to directly quote the individual and re-read the interview when you are writing. It is recommended that you have two recording devices for the interview in case one recording device fails. Most computers, MP3 players, and even cell phones come with recording equipment built in. Many universities also offer equipment that students can check out and use, including computers and recorders. Before you record any interview, be sure that you have permission from your participant.

Transcribing Your Interview

Once your interview is over, you will need to transcribe your interview to prepare it for analysis. The term transcribing means creating a written record that is exactly what was said—i.e. typing up your interviews. If you have conducted an email or chat interview, you already have a transcription and can move on to your analysis stage.

Other than the fact that they both involve asking people questions, interviews and surveys are quite different data collection methods. Creating a survey may seem easy at first, but developing a quality survey can be quite challenging. When conducting a survey, you need to focus on the following areas: survey creation, survey testing, survey sampling, and distributing your survey.

Survey Creation: Length and Types of Questions

One of the keys to creating a successful survey is to keep your survey short and focused. Participants are unlikely to fill out a survey that is lengthy, and you’ll have a more difficult time during your analysis if your survey contains too many questions. In most cases, you want your survey to be something that can be filled out within a few minutes. The target length of the survey also depends on how you will distribute the survey. If you are giving your survey to other students in your dorm or classes, they will have more time to complete the survey. Therefore, five to ten minutes to complete the survey is reasonable. If you are asking students as they are walking to class to fill out your survey, keep it limited to several questions that can be answered in thirty seconds or less. Derek’s survey took about ten minutes and asked students to describe what they ate for a day, along with some demographic information like class level and gender.

Use closed questions to your advantage when creating your survey. A closed question is any set of questions that gives a limited amount of choices (yes/no, a 1–5 scale, choose the statement that best describes you). When creating closed questions, be sure that you are accounting for all reasonable answers in your question creation. For example, asking someone “Do you believe you eat healthy?” and providing them only “yes” and “no” options means that a “neutral” or “undecided” option does not exist, even though the survey respondent may not feel strongly either way. Therefore, on closed questions you may find it helpful to include an “other” category where participants can fill in an answer. It is also a good idea to have a few open-ended questions where participants can elaborate on certain points or earlier responses. How-ever, open-ended questions take much longer to fill out than closed questions.

Survey Creation: Testing Your Survey

To make sure your survey is an appropriate length and that your questions are clear, you can “pilot test” your survey. Prior to administering your survey on a larger scale, ask several classmates or friends to fill it out and give you feedback on the survey. Keep track of how long the survey takes to complete. Ask them if the questions are clear and make sense. Look at their answers to see if the answers match what you wanted to learn. You can revise your survey questions and the length of your survey as necessary.

Sampling and Access to Survey Populations

“Sampling” is a term used within survey research to describe the subset of people that are included in your study. Derek’s first research question was: “Are students’ eating habits at Purdue University healthy or unhealthy?” Because it was impossible for Derek to survey all 38,000 students on Purdue’s campus, he had to choose a representative sample of students. Derek chose to survey students who lived in the dorms because of the wide variety of student class levels and majors in the dorms and his easy access to this group. By making this choice, however, he did not account for commuter students, graduate students, or those who live off campus. As Derek’s case demonstrates, it is very challenging to get a truly representative sample.

Part of the reason that sampling is a challenge is that you may find difficulty in finding enough people to take your survey. In thinking about how get people to take your survey, consider both your everyday surroundings and also technological solutions. Derek had access to many students in the dorms, but he also considered surveying students in his classes in order to reach as many people as possible. Another possibility is to conduct an online survey. Online surveys greatly increase your access to different kinds of people from across the globe, but may decrease your chances of having a high survey response rate. An email or private message survey request is more likely to be ignored due to the impersonal quality and high volume of emails most people receive.

Analyzing and Writing About Primary Research

Once you collect primary research data, you will need to analyze what you have found so that you can write about it. The purpose of analyzing your data is to look at what you collected (survey responses, interview answers to questions, observations) and to create a cohesive, systematic interpretation to help answer your research question or examine the validity of your hypothesis.

When you are analyzing and presenting your findings, remember to work to eliminate bias by being truthful and as accurate as possible about what you found, even if it differs from what you expected to find. You should see your data as sources of information, just like sources you find in the library, and you should work to represent them accurately.

The following are suggestions for analyzing different types of data.

If you’ve counted anything you were observing, you can simply add up what you counted and report the results. If you’ve collected descriptions using a double-entry notebook, you might work to write thick descriptions of what you observed into your writing. This could include descriptions of the scene, behaviors you observed, and your overall conclusions about events. Be sure that your readers are clear on what were your actual observations versus your thoughts or interpretations of those observations.

If you’ve interviewed one or two people, then you can use your summary, paraphrasing, and quotation skills to help you accurately describe what was said in the interview. Just like in secondary research when working with sources, you should introduce your interviewees and choose clear and relevant quotes from the interviews to use in your writing. An easy way to find the important information in an interview is to print out your transcription and take a highlighter and mark the important parts that you might use in your paper. If you have conducted a large number of interviews, it will be helpful for you to create a spreadsheet of responses to each question and compare the responses, choosing representative answers for each area you want to describe.

Surveys can contain quantitative (numerical) and qualitative (written answers/descriptions) data. Quantitative data can be analyzed using a spreadsheet program like Microsoft Excel to calculate the mean (average) answer or to calculate the percentage of people who responded in a certain way. You can display this information in a chart or a graph and also describe it in writing in your paper. If you have qualitative responses, you might choose to group them into categories and/or you may choose to quote several representative responses.

Writing about Primary Research

In formal research writing in a variety of fields, it is common for research to be presented in the following format: introduction/background; methods; results; discussions; conclusion. Not all first year writing classes will require such an organizational structure, although it is likely that you will be required to present many of these elements in your paper. Because of this, the next section examines each of these in depth.

Introduction (Review of Literature)

The purpose of an introduction and review of literature in a research paper is to provide readers with information that helps them under-stand the context, purpose, and relevancy of your research. The introduction is where you provide most of your background (library) research that you did earlier in the process. You can include articles, statistics, research studies, and quotes that are pertinent to the issues at hand. A second purpose in an introduction is to establish your own credibility (ethos) as a writer by showing that you have researched your topic thoroughly. This kind of background discussion is required in nearly every field of inquiry when presenting research in oral or written formats.

Derek provided information from the Food and Drug Administration on healthy eating and national statistics about eating habits as part of his background information. He also made the case for healthy eating on campus to show relevancy:

Currently Americans are more overweight than ever. This is coming at a huge cost to the economy and government. If current trends in increasing rates of overweight and obesity continue it is likely that this generation will be the first one to live shorter lives than their parents did. Looking at the habits of university students is a good way to see how a new generation behaves when they are living out on their own for the first time.

Describing What You Did (Methods)

When writing, you need to provide enough information to your readers about your primary research process for them to understand what you collected and how you collected it. In formal research papers, this is often called a methods section. Providing information on your study methods also adds to your credibility as a writer. For surveys, your methods would include describing who you surveyed, how many surveys you collected, decisions you made about your survey sample, and relevant demographic information about your participants (age, class level, major). For interviews, introduce whom you interviewed and any other relevant information about interviewees such as their career or expertise area. For observations, list the locations and times you observed and how you recorded your observations (i.e. double-entry notebook). For all data types, you should describe how you analyzed your data.

The following is a sample from Jared about his participants:

In order to gain a better understanding of the discourse community in environmental and resource engineering, I interviewed Anne Dare, a senior in environmental and natural resource engineering, and Alyson Keaton an alumnus of Purdue University. Alyson is a current employee of the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS), which is a division of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Here is a sample from Derek’s methods section:

I conducted a survey so that I could find out what students at Purdue actually eat on a typical day. I handed out surveys asking students to record what they ate for a day . . . I received 29 back and averaged the results based on average number of servings from each food group on the old food guide pyramid. The group included students from the freshman to the graduate level and had 8 women and 21 men respond.

Describing Your Study Findings (Results)

In a formal research paper, the results section is where you describe what you found. The results section can include charts, graphs, lists, direct quotes, and overviews of findings. Readers find it helpful if you are able to provide the information in different formats. For example, if you have any kind of numbers or percentages, you can talk about them in your written description and then present a graph or chart showing them visually. You should provide specific details as supporting evidence to back up your findings. These details can be in the form of direct quotations, numbers, or observations.

Jared describes some of his interview results:

Alyson also mentioned the need for phone conversation. She stated, “The phone is a large part of my job. I am communicating with other NRCS offices daily to find out the status of our jobs.” She needs to be in constant contact in order to insure that everything is running smoothly. This is common with those overseeing projects. In these cases, the wait for a response to an email or a memo can be too long to be effective.

Interpreting What You Learned (Discussion)

In formal research papers, the discussion section presents your own interpretation of your results. This may include what you think the results mean or how they are useful to your larger argument. If you are making a proposal for change or a call to action, this is where you make it. For example, in Derek’s project about healthy eating on campus, Derek used his primary research on students’ unhealthy eating and observations of the food courts to argue that the campus food courts needed serious changes. Derek writes, “Make healthy food options the most accessible in every dining hall while making unhealthy foods the least. Put nutrition facts for everything that is served in the dining halls near the food so that students can make more informed decisions on what to eat.”

Jared used the individuals he interviewed as informants that helped him learn more about writing in agricultural and biological engineering. He integrated the interviews he conducted with secondary research to form a complete picture of writing and communication in agricultural and biological engineering. He concludes:

Writing takes so many forms, and it is important to know about all these forms in one way or another. The more forms of writing you can achieve, the more flexible you can be. This ability to be flexible can make all the difference in writing when you are dealing with a field as complex as engineering.

Primary Research and Works Cited or References Pages

The last part of presenting your primary research project is a works cited or references page. In general, since you are working with data you collected yourself, there is no source to cite an external source. Your methods section should describe in detail to the readers how and where the data presented was obtained. However, if you are working with interviews, you can cite these as “personal communication.” The MLA and APA handbooks both provide clear listings of how to cite personal communication in a works cited/references page.

This essay has presented an overview to three commonly used methods of primary research in first year writing courses: observations, interviews, and surveys. By using these methods, you can learn more about the world around you and craft meaningful written discussions of your findings.

- Primary research techniques show up in more places than just first year writing courses. Where else might interviews, surveys, or observations be used? Where have you seen them used?

- The chapter provides a brief discussion of the ethical considerations of research. Can you think of any additional ethical considerations when conducting primary research? Can you think of ethical considerations unique to your own research project?

- Primary research is most useful for first year writing students if it is based in your local community or campus. What are some current issues on your campus or in your community that could be investigated using primary research methods?

- In groups or as a class, make a list of potential primary research topics. After each topic on the list, consider what method of inquiry (observation, interview, or survey) you would use to study the topic and answer why that method is a good choice.

Suggested Resources

For more information on the primary methods of inquiry described here, please see the following sources:

Works Cited

This essay was written by Dana Lynn Driscoll and was published as a chapter in Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing , Volume 2, a peer-reviewed open textbook series for the writing classroom. This work is licensed under the Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) . Please keep this information on this material if you use, adapt, and/or share it.

Contact Info

Kennesaw Campus 1000 Chastain Road Kennesaw, GA 30144

Marietta Campus 1100 South Marietta Pkwy Marietta, GA 30060

Campus Maps

Phone 470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

kennesaw.edu/info

Media Resources

Resources For

Related Links

- Financial Aid

- Degrees, Majors & Programs

- Job Opportunities

- Campus Security

- Global Education

- Sustainability

- Accessibility

470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

© 2024 Kennesaw State University. All Rights Reserved.

- Privacy Statement

- Accreditation

- Emergency Information

- Report a Concern

- Open Records

- Human Trafficking Notice

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Primary Research: What It Is, Purpose & Methods + Examples

As we continue exploring the exciting research world, we’ll come across two primary and secondary data approaches. This article will focus on primary research – what it is, how it’s done, and why it’s essential.

We’ll discuss the methods used to gather first-hand data and examples of how it’s applied in various fields. Get ready to discover how this research can be used to solve research problems , answer questions, and drive innovation.

What is Primary Research: Definition

Primary research is a methodology researchers use to collect data directly rather than depending on data collected from previously done research. Technically, they “own” the data. Primary research is solely carried out to address a certain problem, which requires in-depth analysis .

There are two forms of research:

- Primary Research

- Secondary Research

Businesses or organizations can conduct primary research or employ a third party to conduct research. One major advantage of primary research is this type of research is “pinpointed.” Research only focuses on a specific issue or problem and on obtaining related solutions.

For example, a brand is about to launch a new mobile phone model and wants to research the looks and features they will soon introduce.

Organizations can select a qualified sample of respondents closely resembling the population and conduct primary research with them to know their opinions. Based on this research, the brand can now think of probable solutions to make necessary changes in the looks and features of the mobile phone.

Primary Research Methods with Examples

In this technology-driven world, meaningful data is more valuable than gold. Organizations or businesses need highly validated data to make informed decisions. This is the very reason why many companies are proactive in gathering their own data so that the authenticity of data is maintained and they get first-hand data without any alterations.

Here are some of the primary research methods organizations or businesses use to collect data:

1. Interviews (telephonic or face-to-face)

Conducting interviews is a qualitative research method to collect data and has been a popular method for ages. These interviews can be conducted in person (face-to-face) or over the telephone. Interviews are an open-ended method that involves dialogues or interaction between the interviewer (researcher) and the interviewee (respondent).

Conducting a face-to-face interview method is said to generate a better response from respondents as it is a more personal approach. However, the success of face-to-face interviews depends heavily on the researcher’s ability to ask questions and his/her experience related to conducting such interviews in the past. The types of questions that are used in this type of research are mostly open-ended questions . These questions help to gain in-depth insights into the opinions and perceptions of respondents.

Personal interviews usually last up to 30 minutes or even longer, depending on the subject of research. If a researcher is running short of time conducting telephonic interviews can also be helpful to collect data.

2. Online surveys

Once conducted with pen and paper, surveys have come a long way since then. Today, most researchers use online surveys to send to respondents to gather information from them. Online surveys are convenient and can be sent by email or can be filled out online. These can be accessed on handheld devices like smartphones, tablets, iPads, and similar devices.

Once a survey is deployed, a certain amount of stipulated time is given to respondents to answer survey questions and send them back to the researcher. In order to get maximum information from respondents, surveys should have a good mix of open-ended questions and close-ended questions . The survey should not be lengthy. Respondents lose interest and tend to leave it half-done.

It is a good practice to reward respondents for successfully filling out surveys for their time and efforts and valuable information. Most organizations or businesses usually give away gift cards from reputed brands that respondents can redeem later.

3. Focus groups

This popular research technique is used to collect data from a small group of people, usually restricted to 6-10. Focus group brings together people who are experts in the subject matter for which research is being conducted.

Focus group has a moderator who stimulates discussions among the members to get greater insights. Organizations and businesses can make use of this method, especially to identify niche markets to learn about a specific group of consumers.

4. Observations

In this primary research method, there is no direct interaction between the researcher and the person/consumer being observed. The researcher observes the reactions of a subject and makes notes.

Trained observers or cameras are used to record reactions. Observations are noted in a predetermined situation. For example, a bakery brand wants to know how people react to its new biscuits, observes notes on consumers’ first reactions, and evaluates collective data to draw inferences .

Primary Research vs Secondary Research – The Differences

Primary and secondary research are two distinct approaches to gathering information, each with its own characteristics and advantages.

While primary research involves conducting surveys to gather firsthand data from potential customers, secondary market research is utilized to analyze existing industry reports and competitor data, providing valuable context and benchmarks for the survey findings.

Find out more details about the differences:

1. Definition

- Primary Research: Involves the direct collection of original data specifically for the research project at hand. Examples include surveys, interviews, observations, and experiments.

- Secondary Research: Involves analyzing and interpreting existing data, literature, or information. This can include sources like books, articles, databases, and reports.

2. Data Source

- Primary Research: Data is collected directly from individuals, experiments, or observations.

- Secondary Research: Data is gathered from already existing sources.

3. Time and Cost

- Primary Research: Often time-consuming and can be costly due to the need for designing and implementing research instruments and collecting new data.

- Secondary Research: Generally more time and cost-effective, as it relies on readily available data.

4. Customization

- Primary Research: Provides tailored and specific information, allowing researchers to address unique research questions.

- Secondary Research: Offers information that is pre-existing and may not be as customized to the specific needs of the researcher.

- Primary Research: Researchers have control over the research process, including study design, data collection methods , and participant selection.

- Secondary Research: Limited control, as researchers rely on data collected by others.

6. Originality

- Primary Research: Generates original data that hasn’t been analyzed before.

- Secondary Research: Involves the analysis of data that has been previously collected and analyzed.

7. Relevance and Timeliness

- Primary Research: Often provides more up-to-date and relevant data or information.

- Secondary Research: This may involve data that is outdated, but it can still be valuable for historical context or broad trends.

Advantages of Primary Research

Primary research has several advantages over other research methods, making it an indispensable tool for anyone seeking to understand their target market, improve their products or services, and stay ahead of the competition. So let’s dive in and explore the many benefits of primary research.

- One of the most important advantages is data collected is first-hand and accurate. In other words, there is no dilution of data. Also, this research method can be customized to suit organizations’ or businesses’ personal requirements and needs .

- I t focuses mainly on the problem at hand, which means entire attention is directed to finding probable solutions to a pinpointed subject matter. Primary research allows researchers to go in-depth about a matter and study all foreseeable options.

- Data collected can be controlled. I T gives a means to control how data is collected and used. It’s up to the discretion of businesses or organizations who are collecting data how to best make use of data to get meaningful research insights.

- I t is a time-tested method, therefore, one can rely on the results that are obtained from conducting this type of research.

Disadvantages of Primary Research

While primary research is a powerful tool for gathering unique and firsthand data, it also has its limitations. As we explore the drawbacks, we’ll gain a deeper understanding of when primary research may not be the best option and how to work around its challenges.

- One of the major disadvantages of primary research is it can be quite expensive to conduct. One may be required to spend a huge sum of money depending on the setup or primary research method used. Not all businesses or organizations may be able to spend a considerable amount of money.

- This type of research can be time-consuming. Conducting interviews and sending and receiving online surveys can be quite an exhaustive process and require investing time and patience for the process to work. Moreover, evaluating results and applying the findings to improve a product or service will need additional time.

- Sometimes, just using one primary research method may not be enough. In such cases, the use of more than one method is required, and this might increase both the time required to conduct research and the cost associated with it.