An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Preserving professional identities, behaviors, and values in digital professionalism using social networking sites; a systematic review

Shaista salman guraya, salman yousuf guraya, muhamad saiful bahri yusoff.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Received 2020 Jul 20; Accepted 2021 Jun 24; Collection date 2021.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Despite a rapid rise of use of social media in medical disciplines, uncertainty prevails among healthcare professionals for providing medical content on social media. There are also growing concerns about unprofessional behaviors and blurring of professional identities that are undermining digital professionalism. This review tapped the literature to determine the impact of social media on medical professionalism and how can professional identities and values be maintained in digital era.

We searched the databases of PubMed, ProQuest, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, and EBSCO host using (professionalism AND (professionalism OR (professional identity) OR (professional behaviors) OR (professional values) OR (professional ethics))) AND ((social media) AND ((social media) OR (social networking sites) OR Twitter OR Facebook)) AND (health professionals). The research questions were based on sample (health professionals), phenomenon of interest (digital professionalism), design, evaluation and research type. We screened initial yield of titles using pre-determined inclusion and exclusion criteria and selected a group of articles for qualitative analysis. We used the Biblioshiny® software package for the generation of popular concepts as clustered keywords.

Our search yielded 44 articles with four leading themes; marked rise in the use of social media by healthcare professionals and students, negative impact of social media on digital professionalism, blurring of medical professional values, behaviors, and identity in the digital era, and limited evidence for teaching and assessing digital professionalism. A high occurrence of violation of patient privacy, professional integrity and cyberbullying were identified. Our search revealed a paucity of existing guidelines and policies for digital professionalism that can safeguard healthcare professionals, students and patients.

Conclusions

Our systematic review reports a significant rise of unprofessional behaviors in social media among healthcare professionals. We could not identify the desired professional behaviors and values essential for digital identity formation. The boundaries between personal and professional practices are mystified in digital professionalism. These findings call for potential educational ramifications to resurrect professional virtues, behaviors and identities of healthcare professionals and students.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-021-02802-9.

Keywords: Professionalism, Digital professionalism, Professional identity, Professional behaviors, Professional values, Professional ethics, Social media, Social networking sites, Health professionals

Social media is based on a collection of digital platforms whose content is created, edited and shared by its clients themselves [ 1 ]. The expeditious development of social media has transformed the way healthcare professionals and students interact with each other [ 2 ]. Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, YouTube, Instagram, Wikis, Blogs, Podcasts and WeChat are the most popular social media worldwide [ 3 ]. Medical professionalism is a multi-dimensional construct that refers to a set of skills and competencies that the professionals are expected to practice [ 4 ] The crossroads of medical professionalism and the use of social media has created a new facet of digital professionalism, interchangeable with e-professionalism, that reflects the manifestation of traditional professional attitudes and behaviors through social media [ 5 ]. Digital professionalism refers to the professionals’ use of digital media and the mechanisms in which the profession is evolved by this use [ 6 ].

The concept of digital professionalism in e-health embraces the core values that can steer teaching, learning and practice domains in medical disciplines through online platforms. A safe application of digital professionalism includes professional competence, reputation, and responsibility [ 7 ]. Digital media provides enormous interconnectivity that has expanded our range of opportunities for sharing information. However, this unprecedented opportunity has created interdependency on social media, devices, and users with loss of natural pauses for self-reflection in our livelihood. The ubiquity and easy access of digital media permits free communications that has the potential to thrust its contents into the medical practice.

The fluid and complex nature of medical professional virtues, behaviours and identities are more vulnerable in the current era of digital professionalism [ 8 ]. Professional virtues and behaviours illustrate the processes of how the professionals enact their role, while professional identity involves an oath for adhering to the values and ethics of medical profession associated with the profession such as being trustworthy, competent, and safe medical practitioner. Medical professional identity requires the practicing physician to act as a professional at individual, interpersonal and societal levels [ 9 ]. On the hand, digital professional identity pertains to a wide range of distinct personal and professional acts that are manifested in the digital space [ 10 ]. Unfortunately, literature has reported erosions of professional identities and behaviours in the current era of digital professionalism [ 11 ]. Inappropriate social media behavior has also shown detrimental effects on medical and health sciences students’ approach towards humanism, empathy and altruism [ 5 ]. Unauthorized postings of patient health information, pictures, patient-doctor communication blogs, and images with clear patient identification are commonly witnessed unprofessional behaviors. This practice has blurred personal and professional boundaries in the medical sphere. In digital professionalism, medical educators and policymakers are skeptical about preserving patient confidentiality and privacy on social media [ 12 ].

There are growing concerns about the absence of a structured program for digital professionalism in the medical and health sciences [ 13 , 14 ]. In addition, there is a paucity of literature that can help understand the mechanisms for safe-guarding medical professionals’ identities and values in the digital world [ 15 ]. This systematic review aimed to review the available body of knowledge that can help identify key concepts and threats to professional identity in the era of digital professionalism.

Research questions

Our research questions were based on Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation and Research type (SPIDER) [ 16 ] as shown in Table 1 .

Selection criteria for the studies in this systematic review using SPIDER ( n = 44)

S Sample; PI Phenomenon of Interest; D Design; E Evaluation; R Research type

We framed the following specific questions for our systematic review;

What are the desired values and behaviors of digital professionalism that are needed for maintaining digital professional identity?

What is the impact of social media on medical professionalism?

How can values and behaviors of digital professionalism be made measurable and reproducible in teaching and assessment?

Search strategy

In May 2020, we searched the databases of PubMed, ProQuest, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, and EBSCO host using keywords (professionalism AND (professionalism OR (professional identity) OR (professional behaviors) OR (professional values) OR (professional ethics))) AND ((social media) AND ((social media) OR (social networking sites) OR Twitter OR Facebook)) AND (health professionals) terms and text words for the English language articles published during 1st January 2015 till 30th April, 2020. The search focused on titles about definitions, analyses and relationships of health professionals about professional identity, virtues, behaviors, medical professionalism and digital professionalism.

PubMed was the mainstay to systematically develop a search string, which was later extrapolated to other databases. All selected keywords were searched in the fields “Abstract” and “Article Title” (alternatively “Topic”) and in MeSH/Subject Headings/Thesaurus where available. Language, document type, and publication year restrictions were instead included in the exclusion criteria for the screening process. We defined healthcare professionals in undergraduate, graduate, and continuing education, postgraduates and practicing physicians/nurses, deans, directors, and faculty. For this study we defined healthcare professionals as individuals who may be involved in healthcare delivery (for example: physicians, nurses, dentists, physiotherapists, and pharmacists). A full search log, including detailed search strings for all included information sources, results and notes is available in Appendix I .

Data collection, eligibility criteria and the selection of articles

We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines was used for data mining and selection of the studies for this systematic review [ 17 ].

The original research articles that conducted qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies about definitions of digital professionalism, e-professionalism in the digital age, guidelines for the usage of social media, and the degree and extent of usage of social media by health professionals for educational, professional and personal purposes were included. The participants of the selected studies were medical and allied health sciences students, physicians, faculty and program directors. We excluded systematic reviews, meta-analysis, editorials, and commentaries from our search. The studies about professionalism in non-medical fields were also excluded.

SS reviewed the titles and abstracts of the studies retrieved during initial search and grouped relevant articles for possible inclusion. Then we reviewed full text of the selected articles for their further matching with the inclusion criteria. To mitigate research bias, the entire search process was reviewed by SS, SYG and MSBY. We resolved research disagreements and disputes through discussions until we reached a consensus.

Data extraction and synthesis

This step included review of information from the articles, publication year, author, country of study, single center/multicenter, study level, health professionals’ discipline, ethical approval, methodology, study purpose, results and Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI) [ 18 ] score (Appendix II ) . The data was organized in charts for the descriptive analysis of the quantity and quality of the selected studies.

We performed thematic analysis using emerging concepts and theories from the selected studies, which generated different concepts. The leading themes and concepts were further analyzed in discussion to reach consensus for future implementations. We coded the findings of the selected articles and constructed a coding tree. Later, all researchers critically analyzed preliminary themes, which refined the coding process and helped in adding more strings such as assessment and policy about digital professionalism. We also used biblioshiny® from R Statistical Package to carry out bibliometric analysis [ 19 ]. Using the hierarchical clustering strategy, we labelled each keyword as a cluster item, and then merged clusters with maximum similarity into a large new cluster. Finally, the multiple cluster analysis was graphically generated for review.

Quality assessment

We used the MERSQI tool for the evaluation of studies of quantitative educational research. The MERSQI checklist has 10 items in six domains: study design, sampling, type of data, validity evidence, data analysis, and type of outcomes with a maximum score of three in each domain. A study can have a maximum MERSQI score of 18 (highest quality). SS individually scored each study and in case of score discrepancies, SYG re-assessed the scoring and the results were cross verified among researchers.

Quality assurance

All researchers (SS, SYG and MSBY) objectively reviewed the workflow for the selection of studies. In case of discrepancies, the researchers reached consensus by comparing the studies with inclusion criteria and key words. The discrepancies, inconsistencies and controversies were resolved with consensus until all the concerns were resolved.

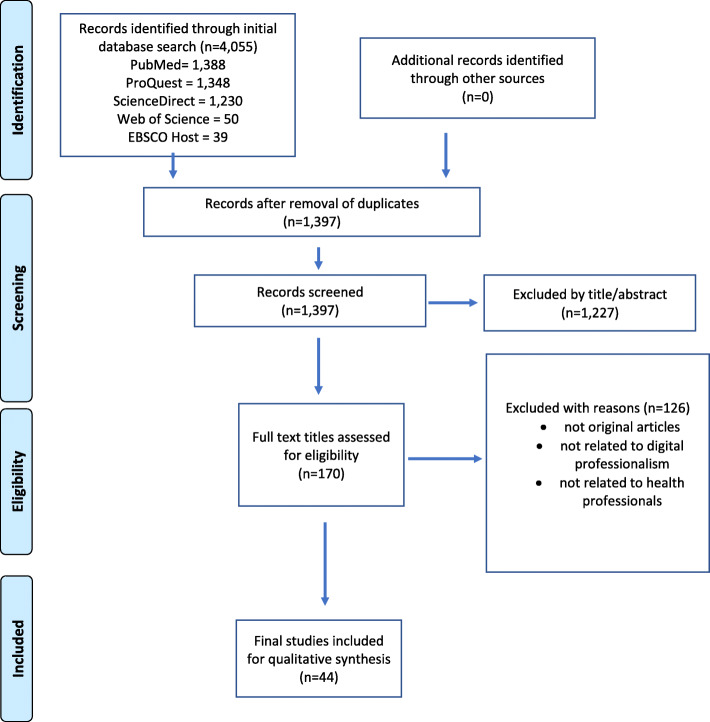

Initial search retrieved 4,055 titles, and after eliminating duplicates and retaining only English language publications, we included 1,319 for further abstract analysis. During the exclusion phase, 1,277 titles were excluded as they could not meet the inclusion criteria. Lastly, 126 full text articles were excluded from the remaining 170 publications. After full paper review, we included 44 articles in our systematic review for deeper analysis. The entire process using PRISMA guidelines is illustrated in Fig. 1 .

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram for the selection of studies in this systematic review

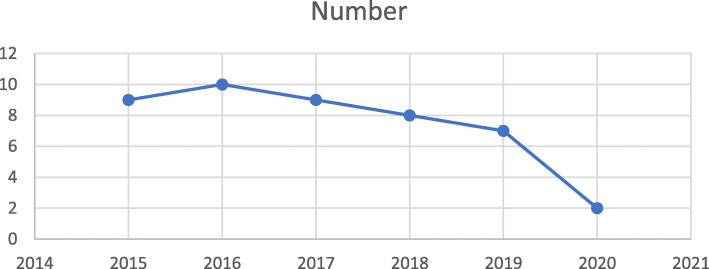

The yearly publication pattern of the selected 44 articles about professional identity, behaviors and virtues in the digital world is shown in Fig. 2 . A maximum number of 10 articles were published in 2016.

The yearly publication pattern of articles about professional identity, behaviors and virtues in the digital world during 2015–2020 ( n = 44). This search was conducted in May 2020, which explains lower number of articles in 2020

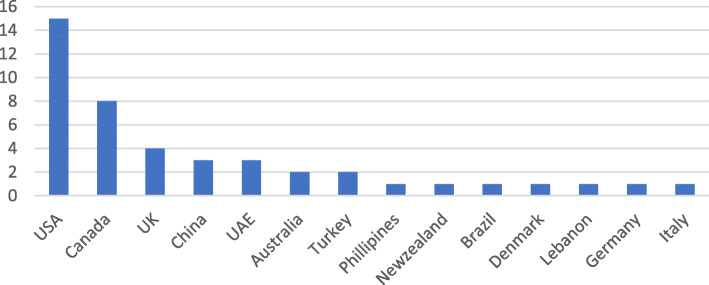

From a different perspective, the graphical representation of countries of origin of the selected 44 studies is displayed in Fig. 3 .

The country-wise pattern of articles published about professional identity, behaviors and virtues in the digital world during 2015–2020 ( n = 44)

Most studies were based in the USA (15/34 %), while other studies were based in Canada (8/18 %), UK (4/9 %), China (3/7 %), UAE (3/7 %), and New Zealand (1/3 %). Most commonly used methodologies were cross-sectional surveys (27/61 %) and analysis of the publicly available Internet content such as Facebook profiles, Twitter streams, or blogs (8/18 %). Other methods used in the selected studies included focus group discussions, mixed-methods by semi-structured interviews and survey. Of note, of all the survey-based studies, about half of these studies had response rates of 50 % or greater, while three studies either did not explicitly report a response rate. For the 11 studies that analyzed the publicly available Internet content, four (36 %) did not mention any methods to increase study rigor of data extraction and analysis expected of content analyses.

Interestingly, 32 (73 %) studies had clear ethical statements either with institutional board approval, exemption, or undertaking that ethical approval was not necessary. Table 2 shows descriptive analysis of the data about medical disciplines and study levels from the selected 44 studies in this systematic review. In terms of study populations, 23 (52 %) involved postgraduates and/or residents, physicians and fellows, and practising nurses, 18 (41 %) included undergraduate students (medical, dental or nursing) while 7 (6 %) conducted studies involved dean, directors, and faculty. Approximately 50 % of survey-based studies had response rates of 50 % or more, and postgraduates & practicing physicians/nurses were the most common group of studied participants.

Descriptive analysis of the data about medical disciplines and study levels from the selected studies in this systematic review (n-44)

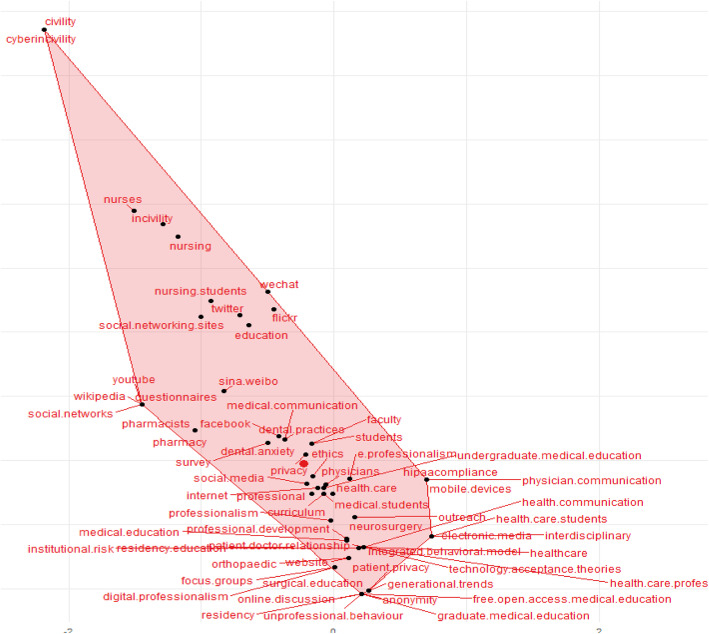

A graphical relationship among the selected keywords for our systematic review using the bibliometric analysis is illustrated in Fig. 4 . The plane distance between keywords reflects the degree of similarity and commonalities among them. The keywords approaching centre of the figure indicate that they have received high attention in the recent years. Probity received maximum attention, while cybercivilty received least attention and similarity with other keywords.

Bibliometric analysis illustrating the cluster and multiple interconnections of frequently used keywords

The analysis of MERSQI showed that 32 quantitative studies had average score of 12, while other 12 qualitative studies did not qualify for quality check. A maximum number of 14 studies had a primary research objective of exploring the beliefs and attitudes of the participants towards usage of social media use and professional behaviours. Other leading research objectives of the selected studies in our systematic review are outlined in Table 3 .

Leading research purposes of the selected studies in this systematic review ( n -44)

Our systematic review generated four main themes;

Usage of social media by healthcare professionals and students [ 1 , 3 , 11 , 20 – 42 ].

The impact of social media on medical professionalism [ 20 , 25 – 29 , 31 , 33 – 35 , 37 , 40 , 41 , 43 – 50 ].

Blurring of professional values, behaviors, and identity in the digital era [ 5 , 11 , 20 , 22 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 31 , 32 , 35 , 37 , 42 , 43 , 46 , 48 , 50 – 56 ].

Limited evidence for teaching and assessing professionalism in the digital era [ 5 , 11 , 20 , 27 , 29 , 31 , 32 , 34 , 42 , 48 , 49 , 54 , 55 ].

By and large, the usage of social media by health professionals has escalated during the last decade [ 1 , 3 , 11 , 20 – 42 , 45 – 49 ], there is a negative impact of social media usage on medical professionalism as reflected by erosion of professional integrity [ 20 , 25 , 29 , 33 – 35 ], an upsurge of awareness about professional identity but rise in unprofessional behaviors in the digital era [ 11 , 20 , 22 , 29 , 32 , 35 , 47 , 48 , 51 , 52 , 57 ] and some evidence of enhanced acquisition of knowledge about digital professionalism by incorporating structured modules in curricula [ 5 , 20 , 27 , 29 , 32 , 34 , 42 , 48 , 49 , 54 , 55 ].

This systematic review reports a rapid rise in the usage of social media by healthcare professionals and students with a negative impact of social media as reflected by substantial unprofessional behaviors leading to blurred professional identities. There is a compelling evidence that the awareness of social media by healthcare professionals and students is getting better, nevertheless, there is a reciprocal increase in the prevalence of unprofessional behaviors in the digital era. We could find limited and unsatisfactory data about the appropriate acquisition of knowledge and structured curriculum for teaching and assessment of digital professionalism. Unfortunately, this review could not identify the desired values and behaviors of digital professionalism that are needed for maintaining digital professional identity. Of all traits of medical professionalism, probity found highest attention in the studies selected in our systematic review. Probity in medical disciplines is an ever needed professional characteristic that enriches the faculty-student and physician-patient relationships with elements of honesty and trust [ 58 ].

The four leading themes of this systematic review are elaborated in the following parts of discussion.

Theme I: Usage of social media by health professionals and students

The use of social media is among the most innovative but, unfortunately, the most destructive necessary evil of the current era. Currently, more than 40 % of the health care consumers use social media for their healthcare needs worldwide [ 59 ]. In medical education, social media is being increasingly used for learning and teaching, research, hospital care quality, and for assessment of online behaviour of healthcare professionals [ 60 ]. Only in the USA, nearly 65 % of the adult population use social media for different reasons and this usage has sharply risen in the last decade [ 61 ]. Understandably this usage is ubiquitous among young adults (90 %) and notable among older adults (77 %), this difference being reflected by being digital native and digital immigrants, respectively.

In medical education, 94 % of medical students, 79 % of medical residents, and 42 % of practicing physicians use social media [ 62 ]. This exponential growth in social media usage provides health information, facilitate live chat platforms for patient-to-patient and patient-to-health professional, data collection on patient perspectives, health promotion and education, and offer telemedicine for online consultations and treatments [ 43 , 63 ]. Use of physician-bloggers has also risen that foster sharing of health information and marketing campaigns. Cognizant with this rise in usage of social media, medical educators, physicians, and students are utilizing contents of social media regardless of its accuracy and authenticity.

Theme II: The impact of social media on medical professionalism

Research has provided compelling evidence that social media has bipolar effect on professionalism [ 3 ] and this has led to erosion of professionalism integrity [ 56 , 64 , 65 ]. In a multi-site survey-based study by Garg et al., most of the identified unprofessional behaviors grouped as high-risk-to-professionalism events (HRTPE) were reported by residents [ 50 ]. The investigators have detailed that HRTPE included posting identifiable patients’ demographics, a clinical or radiological image, and inappropriate pictures of intoxicated colleagues or unprofessional remarks. The study has eluded that such events pose substantial threats to the healthcare professionals and their associated institution. Laliberté at al., have cautioned that due to blurred boundaries between professional and unprofessional territories, the Facebook friendship can potentially lead to mixing of professional and personal lives [ 28 ]. The occurrence of such phenomena is more vulnerable in hospital departments that provide intense and lengthy sessions such as rehabilitation centers.

There is an apparent dissonance between the medical students’ understanding of e-professionalism while using social media and being aware of its impact of losing professional identity [ 31 ]. Social media is considered Powerful, Public and Permanent and the impact of these three Ps potentially carries risk of disseminating misleading and inaccurate information particularly if influenced by confliction and biased interests [ 35 ]. Research has diligently proven that habitual use of social networking sites adversely affects behavioural relations [ 66 ]. In addition, there are growing concerns about negative impact of social media such as extroversion, loneliness, eccentric personality characteristics and social dissonance.

Conversely, literature has reported some benefits of use of social media by health professionals; self-directed learning by staying current, listening to patients’ opinions and needs, and patient education can potentially lead to better patient care [ 27 , 33 , 37 , 41 , 43 , 44 ]. The use of social media offers valid opportunities to enhance engagement, effective feedback, professional collaboration and competence [ 40 ]. Chretien et al., have reported that, using social media, the medical students seemingly benefit from listening to patient perspectives and tend to embrace deeper cultural knowledge [ 26 ]. At the same time, using virtual patient communities on various interfaces of social media can enrich the students’ understanding of the patient perspectives [ 27 ]. Interestingly, non-hand held devices (desktop, laptop) have been shown to have a better impact on development of professional values and behaviors than hand-held devices (mobile phone, iPad, tablets) [ 56 ].

Theme III: Blurring of professional values, behaviors, and identity in the digital era

Our review has identified a wealth of unprofessional behaviors that the researchers have welded with social media in the digital world. These include, but not limited to, indecorous description roles of pharmacists, breaches in the code of patient privacy, and offensive promotion of pharmaceutical products [ 20 ]. Profanity, sexually explicit conducts, derogatory remarks, patient demeaning, references of racism and ethnics, are some other unprofessional behaviors that have been reported in social media [ 51 ]. Physicians mostly publish pictures or other information about their patients on social media and approximately only 5 % of them obtain formal permission from their patients prior to posting [ 22 ]. Interestingly, a study has reported that 89 % physicians believed better quality of care for their patients who are connected to them through Facebook versus other patients [ 47 ]. In a survey-based investigation Marnocha et al., the authors have described that out of 293 nursing students, 77 % had encountered at least one event of unprofessional content posted by fellow students [ 48 ]. Besides, the most recurring types of unprofessional remarks were posted about patients, peers, their work environment (58 %), profanity (37 %), patient privacy (31 %), prejudicial language (29 %) and cyberbullying (11 %). This study has signaled a rising prevalence of unprofessional online behaviours by nursing students and have emphasized the crucial role of policies and formal training of digital professionalism among nursing professionals and educators.

In a report by Lefebvre et al., as many as 80 % of digitally natives were not concerned about patients’ online privacy or data protection [ 29 ]. The same report has revealed that a highest number of nurses in 36–45 years age group believed that making a patient friend or from patient’s family on social media is acceptable. Expression of humor online is considered to be more perilous than face-to-face conversations with patients. Fraping, deliberate posting of inappropriate material on Facebook, after hacking into someone else’s account is a new emerging cyber-crime [ 11 ]. This bring up another aspect of security of cyber networking that can safe-guard public’s privacy and self-esteem [ 32 ]. A study has shown extremely poor awareness about privacy regulations of social media among surgical trainees and established surgeons [ 35 ]. Furthermore, Facebook owners can access all data of their clients that they have uploaded for personal or corporate use. Lastly, a past history of posting unprofessional content on Facebook strongly predicts the occurrence of same event in future as well [ 52 ]. In other words, future professional behavior is predicted by past behaviors.

Social media notifications are a constant source for distraction and stress. Even on silent mode, haptic alerts can still arrive and cause distraction [ 29 ]. All types of notifications such as visual, auditory, or haptic lead to leads to poor work efficiency and memory. Additionally, media updates dismantle emotional states and amplifies stress levels [ 28 ]. Currently, this negative impact of social media on healthcare professionals’ health and well-being is essentially ignored.

The advantages of using social media with positive professional behaviors include sharing patient empathy, effective patient management, online publication of recommended dosage and side-effects of drugs, and rebuttal of misleading health information [ 20 , 26 ]. A study has shown a gradual increase in medical students’ understanding towards considering a change in their online professional behavior [ 5 ]. This change can be attributed to increasing awareness about the deleterious effects of social media. The growing knowledge about ethical and moral use of social media can enhance its positive impact in the medical profession [ 50 , 54 ].

Maintaining professional identity on social media is a daunting task as the boundary between professionalism and unprofessional conduct is delicate and invisible. Educators find it hard to define the extent to which the online identity should be allowed to reflect the concerned professional [ 49 ]. An interesting term of a “dual-citizen model” has been coined that can be applied by creating different online profiles. In a study, the participants were able to generate three leading themes that the authors argued to incorporate into existing curricula; “negotiating identities”, “maintaining distance” and “recognizing and minimizing risks” [ 55 ]. Negotiating identities as students were placed in learning climate without any role in patient care; maintaining distance by separating two crucial but unique roles; and recognizing and minimizing risks by being vigilant to new roles where professionalism might be compromised by social media. This approach can make students aware of their transitional status during their studies that will potentially mitigate risks from consequences of possible transgressions.

Theme IV: Teaching and assessing professionalism in the digital era

Educators have advocated the incorporation of student-centered domains for social media in teaching and assessment [ 20 ]. Since the landscape of social media climate is continuously changing, there is a need for reciprocal curricular interventions to harmonize educational impact in academic institutions. The ensuing adult and active learning would aim at developing professional identities of healthcare professionals and students [ 5 ]. A great majority of medical educators and health policymakers have argued that the use of social media in medical disciplines should be taught early in medical education, and this module should include; professional standards for the use of social media, integration of social media into clinical practice, professional networking [ 49 ], and research [ 27 ]. Furthermore, essential remedial measures should be inculcated into this module that can explain concerns about social media and professionalism [ 29 , 48 ]. These interventional processes would require multidisciplinary and cross-sectoral input from patients, academic and physician leaders, social media experts, and interprofessional stakeholders [ 34 ]. Finally, institutional policies about online privacy, maintaining digital professionalism, protecting medical information of patients, and the sanctions for breaching the policies should be developed and implemented. Research has shown that prior familiarity with social media policies was positively correlated with improved academic performance during online professionalism [ 55 ]. This sheds light on the educational awareness of healthcare professionals and students about online professionalism.

Social media guidance, particularly about the elements of patient confidentiality and privacy is crucial for its appropriate implementation. This may highlight the need to educate all stakeholders for essential self-disclosure for using social media [ 31 ]. Taking an oath or signing a declaration by healthcare professionals and students for adhering to the policies and regulations guidance about social media is a valid but difficult-to-implement option [ 11 ].

In summary, few institutions have incorporated a structured module of e-professionalism in their curricula despite a staggering rise in the use of social media for networking and education. Currently, academic institutional responses to cyber irregularities have typically taken the form of disciplinary actions with punitive intent. This has unintentionally created a hidden curriculum of digital unprofessionalism. This study calls for assistance and guidance in training the digitally enhanced learning in preparation for their future digitally driven clinical practice. Due to the multi-dimensional construct of professionalism, it is hard to assess all domains in the medical field. To add to its complexity, the assessment of digital professionalism is still in its infancy. This review could not identify a reliable and standard assessment tool. However, few studies have indicated initial success by comparing the posts, tweets, content, privacy settings, and personal disclosures using pre-post-intervention [ 34 ] and a longitudinal follow-up [ 52 ] with time and seniority.

Study limitations

The term “digital professionalism” is a relatively recent term, and researchers have been writing about medical students’ and professionals’ behaviour in social media for more than 15 years. Despite these efforts, the quality of research has been found to be of low quality. Secondly, the study was not limited to one study level and has included all healthcare practitioners across the continuum. Furthermore, the studies included in this review were heterogeneous and hence we were not able to investigate the structural differences of the 44 studies due to variations in the type of information provided.

Our systematic review reports an escalating rise of use of social media among health care professionals and students. This study signals unprofessional behaviors on social media among healthcare professionals. Current body of literature reports a high prevalence of breach of patient confidentiality due to an absence of existing social media policies. Nevertheless, there is a corresponding but less strong surge of awareness about the adverse effects of social media. The dignified and noble medical professionals’ identity is blurred and hazy in this digital era. Since the climate of social media is rapidly transforming, there is a need for corresponding curricular modifications that can balance legal and effective use of social media in medical education. This intervention can potentially resurrect professional virtues, behaviors and identities of healthcare professionals and students. This study highlights the need to adapt a unified policy for usage of social media among health professionals and students that can mitigate the risk of cyberbullying, patient confidentiality and professional integrity.

Acknowledgements

SS thanks Dr Bindhu Nair, AHIP Deputy and Research Support Librarian at RCSI-MUB for her expertise and assistance in reviewing the search strategy and study protocol.

Declaration of interest

This systematic review is performed as part of a PhD program in Health Professions Education at Universiti Sains Malaysia. All authors report no declarations of interest.

Abbreviations

Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation and Research type

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument

High-risk-to-professionalism events

Authors' contributions

SS made a substantial contribution to the conception of the work, created the search strategy, conducted the literature search, hand searched and screened the titles and abstract, extracted the data collected, analysed and interpreted the data, drafted the initial manuscript. Other team members SYG and MSBY critically evaluated the search strategy and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All members (SS, SYG and MSBY) approved the final version, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The publication cost of this article will be funded by the RCSI-MUB if accepted by the journal.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this submitted article as Appendix I and II.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Shaista Salman Guraya, Email: [email protected].

Salman Yousuf Guraya, Email: [email protected].

Muhamad Saiful Bahri Yusoff, Email: [email protected].

- 1. Collins K, Shiffman D, Rock J. How Are Scientists Using Social Media in the Workplace? PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0162680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162680. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Smailhodzic E, Hooijsma W, Boonstra A, Langley DJ. Social media use in healthcare: A systematic review of effects on patients and on their relationship with healthcare professionals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1691-0. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Guraya SY, Almaramhy H, Al-Qahtani MF, Guraya SS, Bouhaimed M, Bilal B. Measuring the extent and nature of use of Social Networking Sites in Medical Education (SNSME) by university students: results of a multi-center study. Medical education online. 2018;23(1):1505400. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2018.1505400. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Guraya SY, Sulaiman N, Guraya SS, Yusoff MSB, Roslan NS, Al Fahim M, et al. Understanding the climate of medical professionalism among university students; A multi-center study. Innovations in Education and Teaching International. 2020:1–10.

- 5. Gomes AW, Butera G, Chretien KC, Kind T. The development and impact of a social media and professionalism course for medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2017;29(3):296–303. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2016.1275971. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Gabbard GO. Digital professionalism. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(3):259–63. doi: 10.1007/s40596-018-0994-3. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Ellaway RH, Coral J, Topps D, Topps M. Exploring digital professionalism. Med Teach. 2015;37(9):844–9. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1044956. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Chretien KC, Tuck MG. Online professionalism: A synthetic review. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2015;27(2):106–17. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1004305. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Amending Miller’s pyramid to include professional identity formation. Acad Med. 2016;91(2):180–5. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000913. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Ruan B, Yilmaz Y, Lu D, Lee M, Chan TM. Defining the Digital Self: A Qualitative Study to Explore the Digital Component of Professional Identity in the Health Professions. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(9):e21416. doi: 10.2196/21416. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Curtis F, Gillen J. “I don’t see myself as a 40-year-old on Facebook”: medical students’ dilemmas in developing professionalism with social media. Journal of Further Higher Education. 2019;43(2):251–62. [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Panahi S, Watson J, Partridge H. Social media and physicians: exploring the benefits and challenges. Health informatics journal. 2016;22(2):99–112. doi: 10.1177/1460458214540907. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Ricciardi W. Assessing the impact of digital transformation of health services: Opinion by the Expert Panel on Effective Ways of Investing in Health (EXPH). Eur J Pub Health. 2019;29(Supplement_4):ckz185. 769.

- 14. Regmi K, Jones L. A systematic review of the factors–enablers and barriers–affecting e-learning in health sciences education. BMC medical education. 2020;20:1–18. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02007-6. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Filkins BL, Kim JY, Roberts B, Armstrong W, Miller MA, Hultner ML, et al. Privacy and security in the era of digital health: what should translational researchers know and do about it? American journal of translational research. 2016;8(3):1560. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A, Beyond PICO. the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(10):1435–43. doi: 10.1177/1049732312452938. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Guraya S. Prognostic significance of circulating microRNA-21 expression in esophageal, pancreatic and colorectal cancers; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2018;60:41–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.030. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Reed DA, Cook DA, Beckman TJ, Levine RB, Kern DE, Wright SM. Association between funding and quality of published medical education research. Jama. 2007;298(9):1002–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.9.1002. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Patil S. Global Library & Information Science Research seen through Prism of Biblioshiny. Studies in Indian Place Names. 2020;40(49):157–70. [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Benetoli A, Chen TF, Schaefer M, Chaar B, Aslani P. Pharmacists’ perceptions of professionalism on social networking sites. Research in Social Administrative Pharmacy. 2017;13(3):575–88. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.05.044. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Benetoli A, Chen TF, Schaefer M, Chaar BB, Aslani P. Professional use of social media by pharmacists: a qualitative study. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(9):e258. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5702. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. De Gagne JC, Hall K, Conklin JL, Yamane SS, Roth NW, Chang J, et al. Uncovering cyberincivility among nurses and nursing students on Twitter: A data mining study. International journal of nursing studies. 2019;89:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.09.009. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Dobson E, Patel P, Neville P. Perceptions of e-professionalism among dental students: a UK dental school study. British dental journal. 2019;226(1):73–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2019.11. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Guraya SY, Al-Qahtani MF, Bilal B, Guraya SS, Almaramhy H. Comparing the extent and pattern of use of social networking sites by medical and non medical university students: a multi-center study. Psychology research behavior management. 2019;12:575. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S204389. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Call T, Hillock R. Professionalism, social media, and the Orthopaedic Surgeon: What do you have on the Internet? Technol Health Care. 2017;25(3):531–9. doi: 10.3233/THC-171296. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Chretien KC, Tuck MG, Simon M, Singh LO, Kind T. A digital ethnography of medical students who use Twitter for professional development. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(11):1673–80. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3345-z. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Klee D, Covey C, Zhong L. Social media beliefs and usage among family medicine residents and practicing family physicians. Fam Med. 2015;47(3):222–6. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Laliberté M, Beaulieu-Poulin C, Campeau Larrivée A, Charbonneau M, Samson É. Ehrmann Feldman D. Current uses (and potential misuses) of Facebook: an online survey in physiotherapy. Physiotherapy Canada. 2016;68(1):5–12. doi: 10.3138/ptc.2014-41. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Lefebvre C, McKinney K, Glass C, Cline D, Franasiak R, Husain I, et al. Social media usage among nurses: perceptions and practices. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2020;50(3):135–41. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000857. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Avcı K, Çelikden SG, Eren S, Aydenizöz D. Assessment of medical students’ attitudes on social media use in medicine: a cross-sectional study. BMC medical education. 2015;15(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0300-y. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Duke VJ, Anstey A, Carter S, Gosse N, Hutchens KM, Marsh JA. Social media in nurse education: Utilization and E-professionalism. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;57:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.009. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Kenny P, Johnson IG. Social media use, attitudes, behaviours and perceptions of online professionalism amongst dental students. British dental journal. 2016;221(10):651–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.864. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Pereira I, Cunningham AM, Moreau K, Sherbino J, Jalali A. Thou shalt not tweet unprofessionally: an appreciative inquiry into the professional use of social media. Postgraduate medical journal. 2015;91(1080):561–4. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133353. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Walton JM, White J, Ross S. What’s on YOUR Facebook profile? Evaluation of an educational intervention to promote appropriate use of privacy settings by medical students on social networking sites. Medical education online. 2015;20(1):28708. doi: 10.3402/meo.v20.28708. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Silva DAF, Colleoni R. Patient’s Privacy Violation on Social Media in the Surgical Area. The American Surgeon. 2018;84(12):1900–5. doi: 10.1177/000313481808401235. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Jensen KK, Gögenur I. Nationwide cross-sectional study of Danish surgeons’ professional use of social media. Danish medical journal. 2018;65(9):A5495. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Long X, Qi L, Ou Z, Zu X, Cao Z, Zeng X, et al. Evolving use of social media among Chinese urologists: Opportunity or challenge? PloS one. 2017;12(7):e0181895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181895. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. McKnight R, Franko O. HIPAA compliance with mobile devices among ACGME programs. Journal of medical systems. 2016;40(5):129. doi: 10.1007/s10916-016-0489-2. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Salem J, Borgmann H, Baunacke M, Boehm K, Hanske J, MacNeily A, et al. Widespread use of internet, applications, and social media in the professional life of urology residents. Canadian Urological Association Journal. 2017;11(9):E355. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.4267. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Wagner JP, Cochran AL, Jones C, Gusani NJ, Varghese TK, Jr, Attai DJ. Professional use of social media among surgeons: results of a multi-institutional study. Journal of surgical education. 2018;75(3):804–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.09.008. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Wang Z, Wang S, Zhang Y, Jiang X. Social media usage and online professionalism among registered nurses: A cross-sectional survey. International journal of nursing studies. 2019;98:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.06.001. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Barnable A, Cunning G, Parcon M. Nursing students’ perceptions of confidentiality, accountability, and e-professionalism in relation to facebook. Nurse Educator. 2018;43(1):28–31. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000441. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Campbell L, Evans Y, Pumper M, Moreno MA. Social media use by physicians: a qualitative study of the new frontier of medicine. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2016;16(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12911-016-0327-y. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Phillips HW, Chen J-S, Wilson B, Udawatta M, Prashant G, Nagasawa D, et al. Social media use for professional purposes in the neurosurgical community: a multi-institutional study. World neurosurgery. 2019;129:e367-e74. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.05.154. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Neville P. Social media and professionalism: a retrospective content analysis of Fitness to Practise cases heard by the GDC concerning social media complaints. British dental journal. 2017;223(5):353. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.765. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Bacaksiz FE, Eskici GT, Seren AKH. “From my Facebook profile”: What do nursing students share on Timeline, Photos, Friends, and About sections? Nurse education today. 2020;86:104326. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ]

- 47. Desai DG, Ndukwu JO, Mitchell JP. Social Media in Health Care: How Close Is Too Close? The health care manager. 2015;34(3):225 – 33. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ]

- 48. Marnocha S, Marnocha MR, Pilliow T. Unprofessional content posted online among nursing students. Nurse Educ. 2015;40(3):119–23. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000123. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Henning MA, Hawken S, MacDonald J, McKimm J, Brown M, Moriarty H, et al. Exploring educational interventions to facilitate health professional students’ professionally safe online presence. Med Teach. 2017;39(9):959–66. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1332363. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Garg M, Pearson DA, Bond MC, Runyon M, Pillow MT, Hopson L, et al. Survey of individual and institutional risk associated with the use of social media. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2016;17(3):344. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2016.2.28451. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. Parmar N, Dong L, Eisingerich AB. Connecting with your dentist on facebook: patients’ and dentists’ attitudes towards social media usage in dentistry. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(6):e10109. doi: 10.2196/10109. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 52. Koo K, Bowman MS, Ficko Z, Gormley EA. Older and wiser? Changes in unprofessional content on urologists’ social media after transition from residency to practice. BJU Int. 2018;122(2):337–43. doi: 10.1111/bju.14363. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 53. Dimitri D, Gubert A, Miller AB, Thoma B, Chan T. A quantitative study on anonymity and professionalism within an online free open access medical education community. Cureus. 2016;8(9). [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- 54. Lefebvre C, Mesner J, Stopyra J, O’Neill J, Husain I, Geer C, et al. Social media in professional medicine: new resident perceptions and practices. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(6):e119. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5612. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 55. Khandelwal A, Nugus P, Elkoushy MA, Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Smilovitch M, et al. How we made professionalism relevant to twenty-first century residents. Med Teach. 2015;37(6):538–42. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.990878. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 56. Mariano MCO, Maniego JCM, Manila HLMD, Mapanoo RCC, Maquiran KMA, Macindo JRB, et al. Social media use profile, social skills, and nurse-patient interaction among registered nurses in tertiary hospitals: a structural equation model analysis. International journal of nursing studies. 2018;80:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.12.014. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 57. Chretien K, Tuck M, Simon M, Singh L, Kind T, Chretien KC, et al. A Digital Ethnography of Medical Students who Use Twitter for Professional Development. JGIM: Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2015;30(11):1673-80. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- 58. Guraya SY. Comparing recommended sanctions for lapses of academic integrity as measured by Dundee Polyprofessionalism Inventory I: Academic integrity from a Saudi and a UK medical school. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association. 2018;81(9):787–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2018.04.001. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 59. Surani Z, Hirani R, Elias A, Quisenberry L, Varon J, Surani S, et al. Social media usage among health care providers. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):654. doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2993-y. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 60. Riddell J, Brown A, Kovic I, Jauregui J. Who Are the Most Influential Emergency Physicians on Twitter? West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(2):281–7. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2016.11.31299. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 61. Perrin A. Social media usage. Pew research center. 2015:52–68.

- 62. Shah V, Kotsenas AL. Social media tips to enhance medical education. Academic Radiology. 2017;24(6):747–52. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2016.12.023. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 63. Masters KLT, Johannink J, Al-Abri R, Herrmann-Werner A. Surgeons’ Interactions With and Attitudes Toward E-Patients: Questionnaire Study in Germany and Oman. Journal of medical Internet research 2020;22 ((3)). [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- 64. Guraya SY, Norman RI, Roff S. Exploring the climates of undergraduate professionalism in a Saudi and a UK medical school. Med Teach. 2016;38(6):630–2. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2016.1150987. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 65. Guraya SY, Norman RI, Khoshhal KI, Guraya SS, Forgione A. Publish or Perish mantra in the medical field: A systematic review of the reasons, consequences and remedies. Pakistan journal of medical sciences. 2016;32(6):1562. doi: 10.12669/pjms.326.10490. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 66. Akram W, Kumar R. A study on positive and negative effects of social media on society. International Journal of Computer Sciences Engineering. 2017;5(1):351–4. doi: 10.26438/ijcse/v5i10.351354. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data availability statement.

- View on publisher site

- PDF (1.2 MB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Professional identity in nursing: A mixed method research study

Affiliations.

- 1 Nursing Science Program, Adelaide Nursing School, Faculty of Health and Medical Science, University of Adelaide, Level 4, Adelaide Health and Medical Science Building, Corner North Terrace and George Street, Adelaide, South Australia 5005, Australia. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Adelaide Nursing School, Faculty of Health and Medical Science, University of Adelaide, Level 4, Adelaide Health and Medical Science Building, Corner North Terrace and George Street, Adelaide, South Australia 5005, Australia.

- 3 Department/Reader Glasgow Caledonian University, Room A401, Govan Mbeki Building Cowcaddens Road, Glasgow G4 0BA, Scotland, UK.

- 4 Glasgow Caledonian University, Cowcaddens Road, Glasgow G4 0BA, Scotland, UK.

- PMID: 33823376

- DOI: 10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103039

Professional identity is developed through a self-understanding as a nurse along with experience in clinical practice and understanding of their role. Personal and professional factors can influence its development. A recent integrative literature review synthesised factors that influenced registered nurse's perceptions of their professional identity into three categories of the self, the role and the context of nursing practice. This review recommended that further research was needed into professional identity and how factors and perceptions changed over time. The aims of this study were to explore registered nurses' understanding of professional identity and establish if it changed over time. A mixed-methods study using a two-stage design with an on-line survey and focus groups was implemented with registered nurses who were studying nursing at a postgraduate level in Australia or Scotland. The reported influences on professional identity related to the nurse, the nursing role, patient care, the environment, the health care team and the perceptions of nursing. Professional development and time working in the profession were drivers of changes in thinking about nursing, their role and working context and their professional identity. Additionally, participants sought validation of their professional identity from others external to the profession.

Keywords: Education; Mixed methods research; Nursing; Professional identity; Registered nurses.

Copyright © 2021 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Nurse's Role*

- Qualitative Research

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 05 July 2019

The importance of professional values from nursing students’ perspective

- Batool Poorchangizi 1 ,

- Fariba Borhani 2 ,

- Abbas Abbaszadeh 3 ,

- Moghaddameh Mirzaee 4 &

- Jamileh Farokhzadian 5

BMC Nursing volume 18 , Article number: 26 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

358k Accesses

98 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

Professional values of nursing students may be changed considerably by curricula. This highlights the importance of the integration of professional values into nursing students’ curricula. The present study aimed to investigate the importance of professional values from nursing students’ perspective.

This cross-sectional study was conducted at the Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Iran. Data were gathered by using a two-section questionnaire consisting of demographic data and Nursing Professional Values Scale-Revised (NPVS-R). By using the stratified random sampling method, 100 nursing students were included in the study.

Results showed that the mean score of the students’ professional values was at high level of importance (101.79 ± 12.42). The most important values identified by the students were “maintaining confidentiality of patients” and “safeguarding patients’ right to privacy”. The values with less importance to the students were “participating in public policy decisions affecting distribution of resources” and “participating in peer review”. The professional value score had a statistically significant relationship with the students’ grade point average ( P < 0.05).

Conclusions

In light of the low importance of some values for nursing students, additional strategies may be necessary to comprehensively institutionalize professional values in nursing students.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Values are goals and beliefs that establish a behavior and provide a basis for decision making [ 1 ]. In a profession, values are standards for action that are preferred by experts and professional groups and establish frameworks for evaluating behavior [ 2 ]. Nursing is a profession rooted in professional ethics and ethical values, and nursing performance is based on such values. Core values of nursing include altruism, autonomy, human dignity, integrity, honesty and social justice [ 3 ]. The core ethical values are generally shared within the global community, and they are a reflection of the human and spiritual approach to the nursing profession. However, the values in the care of patients are affected by cultural, social, economic, and religious conditions dominating the community, making it essential to identify such values in each country [ 4 ].

Professional values are demonstrated in ethical codes [ 5 ]. In fact, ethical codes clarify nursing profession practices, the quality of professional care, and professional norms [ 2 ]. Advances in technology and expansion of nursing roles have provoked complex ethical dilemmas for nurses. Such dilemmas, if not dealt with properly, negatively affect the ability of novice nurses to make clinical decisions [ 6 ]. With the ever-increasing number and complexity of ethical dilemmas in care settings, promotion of professional values has become more crucial in nursing education. The acquisition and internalization of values are at the center of promoting the nursing profession [ 2 ]. When values are internalized, they will become the standards in practice and guide behavior [ 7 ]. Values can be taught, modified and promoted directly or indirectly through education [ 8 ]. Each student enters the nursing school with a set of values that might be changed during the socialization process [ 9 ]. Purposeful integration of professional values in nursing education is essential to guaranteeing the future of nursing [ 10 , 11 ].

One of the significant consequences of teaching ethics and professional values to students is increasing their capacity for autonomous ethical decision-making [ 12 ]. Nursing students acquire professional values initially through the teaching of their school educators and the socialization process. Professional socialization is the method of developing the values, beliefs, and behaviors of a profession [ 13 ]. In their study, Seda and Sleem reported a significant relationship between professional socialization of students and improvement of professional values [ 9 ]. Through professional socialization, which results in the complete acquisition and internalization of values, nursing students should acquire necessary skills and knowledge in cognitive, emotional, and practical dimensions. Presently, however, less attention is paid to the emotional dimension in the formation of values compared to the other two [ 14 ]. In order to develop a value system, individuals should reach the fourth or fifth level of learning of Bloom’s affective domain, i.e. organization and internalization of values. At this level, stabilization of values requires passage of time [ 15 ].

Studies have shown that education causes differences in the formation of professional values, and that nursing educators have significant influence on the stimulation of professional values [ 8 , 14 , 16 , 17 ]. Wehrwein reported that education related to ethics was effective when students’ awareness of ethical issues increased along with the application of values in the workplace. In addition, the ability to make ethical decisions was reported to be stronger in students who had passed an ethics course compared to those who had not [ 18 ]. Therefore, nursing educators play a key role in determining the future way in which nurses grow professionally and are prepared to confront new, unavoidable challenges [ 9 ].

Professors and educators, both in clinical settings and at each stage of education, have the role of facilitator in developing students’ perception of the nursing profession and the nurse’s role. Students may increase their commitment to professional values directly through role playing and indirectly through observing behaviors related to professional values [ 14 ]. Nursing educators are effective role models because of their clinical skills, sense of responsibility, professional commitment, and personal characteristics such as kindness, flexibility, and honesty. Nursing educators enhance creative learning by encouraging critical thinking and decision-making, establishing a supportive learning environment, having technical and ethical knowledge, and providing opportunities for fair evaluation and feedback. Nursing educators should teach nursing students effective strategies to confront ethical dilemmas [ 12 ].

Students’ perspectives on professional values influence their approach to applying professional values in their future profession [ 14 , 15 , 19 , 20 ]. Nursing educators need additional awareness of nursing students’ perspectives on importance of professional values as a basis to use more effective methods for applying professional values. Therefore, nursing educators are able to educate graduates who are ready for decision-making and can effectively deal with daily ethical challenges. Nursing educators’ and students’ awareness of professional nursing values is important for preparing nurses to provide care of patients in an ethical and professional manner [ 6 ]. Researchers have found insufficient information about nursing students’ professional values in Iran. Because of the potential impact of cultures and clinical environments on professional values, the present study aimed to examine the importance of professional values from nursing students’ perspective.

Study design and setting

This cross-sectional study was performed from February to May 2016 at the Razi Nursing and Midwifery School affiliated with the Kerman University of Medical Sciences (KUMS), in Kerman, Iran. This study is a part of a larger study. The results of the first part was published in previous study [ 21 ].

The participants included all undergraduate nursing students who were studying at the time of data collection ( n = 177). The sample size ( n = 106) was determined based on the Cochran formula ( d = 0.06, p = 0.05). Inclusion criteria were undergraduate nursing students in the fourth, sixth, and eighth semesters without official work experience in hospitals. Submitting an incomplete questionnaire was considered an exclusion criterion. The participants were selected using a stratified random sampling based on the proportion of students in each semester. Therefore, among the total of 50, 62, and 65 students in the three semesters, 30, 37, and 39 students were enrolled, respectively. Finally, of the remaining 106 students, 100 students completed the questionnaires, but six students did not return the questionnaires. Thus, the final sample consisted of 100 students (with the response rate of 94.34%).

A two-section questionnaire was used for data collection. The students’ demographic data including age, grade point average (GPA: 17–20 (level A), 13–16 (level B) and ≤ 12 (level C)), ethnicity, gender, marital status, economic status of family, educational semester, and participation in professional ethical training courses was collected by the first section. The second section was Weis and Schank’s Nursing Professional Values Scale-Revised (NPVS-R). The NPVS-R is a potentially useful instrument for measuring professional nursing values. In developing the professional values scale, Weis and Schank used the ANA Code of Ethics as well as the studies on nursing values and their promotion among nurses [ 2 ].

We used the Persian version of the NPVS-R in this study. The validity of the translated questionnaire was confirmed using face and content validity as well as expert opinion. Reliability of the NPVS-R was reported to be 0.91 using Cronbach’s alpha [ 22 ]. To establish reliability of the NPVS-R in Persian, a pilot study was conducted with 20 nursing students, which resulted in a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.90.

The NPVS-R includes 26 items with a Likert-scale format in five dimensions: 1) trust: 5 items, 2) justice: 3 items, 3) professionalism: 4 items, 4) activism: 5 items, and 5) caring: 9 items. The trust dimension reflects the nurse’s duty (the value of veracity) to patients. The justice dimension deals with patients as noted in statements reflecting equality and diversity issues. The professionalism dimension reflects the promotion of nursing competence, self-evaluation and reflection, and seeking professional growth. The activism dimension reflects participation in professional activities and solutions to professional problems. The caring dimension reflects respect for patients and protection of patient rights.

The participants specified the importance of each item on a Likert 5-point scale ranging from 1 to 5 with 1 = not important, 2 = somewhat important, 3 = important, 4 = very important, and 5 = the most important. The possible range of scores is 26 to 130 [ 2 ]. In this study, the scores below 43, scores between 43 and 86, and those above 86 were considered low importance, moderate, and high importance, respectively. A higher score indicates that professional values are very important, and that nurses are more oriented toward stronger professional values.

Data collection

The first researcher distributed the questionnaires among the participants and explained the study objectives. The researcher also explained to the participants how to fill out the questionnaires and asked them to specify the importance of professional values. In order to eliminate any ambiguity regarding questionnaire items, necessary explanations were provided. The researcher collected the questionnaires while maintaining anonymity and confidentiality of the data.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage, mean and standard deviation) and inferential statistics (independent samples, t- test, analysis of variance (ANOVA), Mann-Whitney, and Pearson’s correlation coefficient) were used. SPSS software version 19 was used for data analysis and level of significance was considered p ≤ 0.05.

Ethical considerations

First, the study was approved by the ethics committee affiliated to the Kerman University of Medical Sciences (No code: 1394.238). Then, official permission for collecting data was obtained from the Razi Nursing and Midwifery School. Prior to distributing the questionnaire, the researcher guaranteed the confidentiality and anonymity of the questionnaires. The students’ informed consent was implied from returning completed questionnaires.

The results showed that the students’ mean age was) 21.9 ± 1.26 (and GPA was at B level (16.20 ± 1.20). Most of the students were female (75%), single (67%), and Iranian (97%). Around 37% of the students were in the eighth semester, and around 37.6% of the students had participated in professional ethical training courses (Table 1 ).

The high mean score of the professional values of the nursing students indicated high awareness and perception of the importance of professional values from the students’ perspective. The most important values as identified by higher mean scores were respectively as follows: “maintaining confidentiality of patients”, “safeguarding patients’ right to privacy”, “assuming responsibility for meeting health needs of the culturally diverse population”, and “maintaining competency in area of practice”. The values with lower mean scores were “participating in public policy decisions affecting distribution of resources”, “participating in peer review”, “recognizing role of professional nursing associations in shaping healthcare policy” and “participating in nursing research and/or implementing research findings appropriate to practice”, respectively (Table 2 ).

The results of the Pearson’s correlation coefficient test indicated that there was no significant relationship between professional values and age ( r = 0.03, p = 0.47), while there was a significant relationship between professional values and the GPA ( r = 0.29, p = 0.003). This revealed that the students with higher GPA had higher scores in professional values. There was no significant difference in the students’ professional values based on different educational semesters ( F = 0.29, p = 0.74). In addition, there were no significant differences in professional values based on the other demographic variables such as gender, marital status, ethnicity, and participation in professional ethical training courses (p > 0.05) (Table 1 ).

The present study was conducted to examine the importance of professional values from nursing students’ perspectives. The results showed a high total score with regard to the importance of professional values. These findings are in agreement with the findings of the studies conducted in the United States [ 15 , 23 ], Taiwan [ 24 ], Korea [ 25 ], and Iran [ 21 ]. Results of these studies highlighted that instructors and nursing trainers were seen as role models by students.

In this study, the most important nursing professional values were “maintaining confidentiality of patients”, “safeguarding patients’ right to privacy”, “responsibility for meeting health needs of the culturally diverse population”, and “maintaining competency in area of practice”. The results of this study are in agreement with the results of the studies conducted by Lin et al. [ 19 ], Clark [ 15 ], Fisher [ 23 ], and Leners et al. [ 8 ], who identified these values as the most important values. One possible reason for the consistency between the results of this study and those of the other studies may be that these values are among the main values in the nursing profession and are closely associated with it. Leners et al. reported that maintaining competency in area of practice, accepting responsibility and accountability for own practice, and safeguarding patients’ right to privacy were values prioritized by students. Since these values are associated with the direct care of patients and given that students complete their clinical practices under supervision of nurses, students may learn the importance of these values through role modeling and application in clinical settings [ 8 ].

In this study, the least important values from the students’ perspective were “participating in public policy decisions affecting distribution of resources”, “participating in peer review”, “recognizing role of professional nursing associations in shaping healthcare policy”, and “participating in nursing research and/or implementing research findings appropriate to practice” . The results of this research are also in agreement with the results of the studies conducted by Lin et al. [ 19 ], Clark [ 15 ], Fisher [ 23 ], and Leners et al. [ 8 ]. A multitude of factors may have contributed to the lower importance placed on these values; some causes might be less information about the importance of these values in the development of the profession, low motivation, insufficient affirmation, and low encouragement by nursing educators.

The reason for the low importance placed on the values such as “participating in nursing research and/or implementing research findings appropriate to practice” might be the fact that nursing students do not acquire necessary skills (such as information literacy skills) to apply in evidence-based practices during their academic days [ 26 , 27 ]. Another reason for the low importance of the above-mentioned values might be graduate education programs; undergraduate students focus on the rules of clinical practice because they are novices. As they become more competent and eventually experts, the ranking of the values is likely to change.

Concerning the lower importance of the “recognizing role of professional nursing associations in shaping healthcare policy” value, Esmaeili et al. reported the following items as causes for reduction of participation in such associations: long working hours, lack of awareness about the associations’ objectives and activities, insufficiency of time, and lack of support from hospitals to play active roles in associations. Moreover, the inactivity of members in such associations and the weak relationship among these associations were other barriers confronted by such associations in Iran [ 28 ]. In addition, one other reason might be that nursing educators themselves do not participate in professional nursing associations because of high workloads and limited time. Professional nursing associations play major roles in promoting nursing authority and professional identity. Consequently, understanding and valuing the importance of participation in professional associations may require emphasis as an important professional value.

Regarding the low importance of values such as “participating in peer review” and “participating in public policy decisions affecting distribution of resources”, it can be mentioned that these activities are part of the manager’s duties, and that the nurses are not involved in peer evaluation and policy decisions.

In this study, a significant relationship was found between the GPA and scores of professional values. Students with high GPA Probably have the necessary scientific competency in their professional performance, which may result in giving higher importance to professional values as a significant index of professional competence. Lechner et al. emphasized that academic environments appear to elicit and reinforce values such as developing one’s capacities and pursuing one’s interests [ 29 ].

In this study, although no significant difference was found between educational semester and the students’ scores of professional values, the highest score was related to the sixth semester whereas the lowest score was related to the fourth semester. The studies conducted by Rassin [ 16 ] and Clark [ 15 ] had results similar to those of this study, with no difference found between total scores of professional values of students in different semesters of their nursing education. However, several studies [ 8 , 14 , 25 ] found significant differences between total scores of professional values of students in different semesters. It is difficult to compare these differences due to the use of different instruments to measure professional values, differences in nursing education curricula and environments, and differences in study designs. In line with the results found on the association between academic year and education with professional values, researchers reported in several studies that education had a positive effect on professional values, and nursing students’ education experience increased total scores of professional values in a positive direction from entry into school until graduation [ 8 , 14 , 19 ]. In their study, Weis and Shank concluded that higher focus on curricula of junior and senior students could change some professional values, indicating that time spent in school was associated with change in values [ 30 ].