5 Exact Examples: How to Write a Strong Self-Evaluation

By Status.net Editorial Team on December 18, 2023 — 15 minutes to read

Self-evaluation, also known as self-assessment, is a process where you critically examine your own actions, behaviors, values, and achievements to determine your strengths, weaknesses and areas for development. This type of evaluation is commonly a part of performance reviews at companies, but you can also practice it independently to positively impact your career and personal growth. Writing an effective self-evaluation requires honesty, introspection, and clear communication.

Getting Started

Reflect on your achievements.

Before diving into a self-evaluation, take some time to reflect on your successes throughout the review period. Jot down a list of milestones, completed projects, and goals you’ve met. This exercise allows you to not only celebrate your accomplishments but also gives you a starting point for the evaluation. For example, “Launched a successful marketing campaign, resulting in an 8% increase in leads.”

Identify Areas for Growth

After reflecting on your achievements, Shift your focus to the areas where you can improve. This requires being honest with yourself about your weaknesses and challenges you’ve faced during the review period. Write down examples where you struggled and think about what could have been done differently. Here’s an example: “I struggled to meet deadlines on two major projects because I underestimated the time needed for completion.”

Gather Feedback

A self-evaluation is an opportunity to hear and incorporate feedback from your colleagues. Ask for constructive feedback from trusted coworkers and jot down their suggestions. Be sure to consider their perspectives when writing your self-evaluation. For example, a coworker might say, “You were a great team player during the project, but your communication could be more timely.”

Review Your Job Description

Finally, review your job description to ensure you have a clear understanding of your role and responsibilities. Use this as a reference point to measure your performance and ensure your evaluation covers all aspects of your job. This will help you to focus on key goals and responsibilities you should address in your self-evaluation. For instance, if your job description states, “Collaborate effectively with the sales team to generate new leads,” think about how you’ve fulfilled this responsibility and include specific examples in your evaluation.

Self-Evaluation Template

Introduction: – Begin by summarizing your role and the primary responsibilities you hold within the organization. – Highlight any overarching goals or objectives that were set for the evaluation period.

Key Accomplishments: – List your significant achievements since the last evaluation, providing specific examples. – Detail how these accomplishments have positively impacted the team or organization. – Use metrics and data where possible to quantify your success.

Strengths and Skills: – Identify the skills and strengths that have contributed to your achievements. – Provide examples of how you have demonstrated these strengths in your work.

Areas for Improvement: – Reflect on any challenges you faced and areas where you see opportunities for personal growth. – Outline your plan for addressing these areas and how you intend to implement changes.

Professional Development: – Discuss any new skills or knowledge you have acquired. – Explain how you have applied or plan to apply this new expertise to your current role.

Goals for the Next Period: – Set clear, achievable goals for the next evaluation period. – Explain how these goals align with the organization’s objectives and your professional development.

Conclusion: – Summarize your contributions and express your commitment to ongoing improvement and excellence. – Offer to discuss any feedback or support you may need from management to achieve your future goals.

[Your Name] Self-Evaluation

Introduction : My role as [Your Job Title] at [Company Name] involves [briefly describe your main responsibilities]. Over the past [timeframe], I have aimed to [state your overarching goals or objectives].

Key Accomplishments: 1. [Accomplishment 1]: [Description and impact]. 2. [Accomplishment 2]: [Description and impact]. 3. [Accomplishment 3]: [Description and impact].

Strengths and Skills: – [Strength/Skill 1]: [Example of how you demonstrated this]. – [Strength/Skill 2]: [Example of how you demonstrated this]. – [Strength/Skill 3]: [Example of how you demonstrated this].

Areas for Improvement: – [Area for Improvement 1]: [Your plan to improve]. – [Area for Improvement 2]: [Your plan to improve].

Professional Development: – [New Skill/Knowledge]: [How you have applied or plan to apply it].

Goals for the Next Period: – [Goal 1]: [How it aligns with organizational/professional objectives]. – [Goal 2]: [How it aligns with organizational/professional objectives].

Conclusion: I am proud of what I have accomplished in [timeframe] and am eager to continue contributing to [Company Name]. I am committed to [specific actions for improvement and goals], and I look forward to any feedback that can help me grow further in my role. I would appreciate the opportunity to discuss any additional support needed from management to succeed in my endeavors.

[Optional: Request for meeting or discussion with supervisor]

Example of a Strong Self-Evaluation

Jane Smith Self-Evaluation

Introduction: As a Senior Graphic Designer at Creative Solutions Inc., my role involves conceptualizing and designing visual content that effectively communicates our clients’ branding and marketing objectives. Over the past year, I have aimed to enhance the creativity and efficiency of our design output, ensuring client satisfaction and team growth.

Key Accomplishments: 1. Brand Campaign Launch: Led the design team in creating a comprehensive visual campaign for our key client, Luxe Cosmetics, which resulted in a 40% increase in their social media engagement within two months. 2. Workflow Optimization: Implemented a new design workflow using Agile methodologies that reduced project turnaround time by 25%, allowing us to take on 15% more client work without compromising quality. 3. Design Award: Received the “Innovative Design of the Year” award for my work on the EcoGreen initiative, which raised awareness about sustainable living practices through compelling visual storytelling.

Strengths and Skills: – Creativity and Innovation: Consistently pushed the boundaries of traditional design to create fresh and engaging content, as evidenced by the Luxe Cosmetics campaign. – Team Leadership: Fostered a collaborative team environment that encouraged the sharing of ideas and techniques, leading to a more versatile and skilled design team. – Efficiency: Streamlined design processes by introducing new software and collaboration tools, significantly improving project delivery times.

Areas for Improvement: – Public Speaking: While I am confident in my design skills, I aim to improve my public speaking abilities to more effectively present and pitch our design concepts to clients. – Advanced Animation Techniques: To stay ahead in the industry, I plan to enhance my knowledge of animation software to expand our service offerings.

Professional Development: – Advanced Adobe After Effects Course: Completed a course to refine my animation skills, which I plan to leverage in upcoming projects to add dynamic elements to our designs.

Goals for the Next Period: – Client Retention: Aim to increase client retention by 20% by delivering consistently high-quality designs and improving client communication strategies. – Mentoring: Establish a mentoring program within the design team to nurture the development of junior designers, ensuring a pipeline of talent and leadership for the future.

Conclusion: I am proud of the contributions I have made to Creative Solutions Inc. this year, particularly in enhancing our design quality and team capabilities. I am committed to further developing my public speaking skills and expanding our animation services, and I look forward to any feedback that can help me progress in these areas. I would appreciate the opportunity to discuss additional resources or support from management that could facilitate achieving these goals.

Best regards, Jane Smith

Writing Your Self-Evaluation

Follow the company format.

Before you begin writing your self-evaluation, make sure to check with your organization’s guidelines and format. Adhering to the provided template will ensure that you include all relevant information, making it easier for your supervisors to review. You may also find examples and tips within the company resources that can help you present your achievements and goals in a concise and effective manner.

Start with Your Successes

When writing a self-evaluation, it’s essential to highlight your accomplishments and contributions positively. List your achievements and victories, focusing on those that align with the organization’s goals and values. Back up your claims with specific examples and statistics, if available. This not only showcases your hard work but also reinforces your value to the company.

For instance, if you surpassed a sales target, mention the exact percentage you exceeded and describe how you achieved this. Or if you successfully led a team project, outline the steps you took to manage and motivate your colleagues.

Discuss Your Challenges

While it’s important to discuss your successes, acknowledging your challenges and areas of improvement demonstrates self-awareness and commitment to personal growth. Don’t shy away from admitting where you struggled—instead, be honest and identify these obstacles as opportunities for development. Explain what actions you’re taking to improve, like attending workshops, seeking feedback, or collaborating with colleagues.

For example, if you faced difficulties managing your time, discuss the strategies you’ve implemented to stay organized and prioritize tasks more effectively.

Set Goals for Yourself

Setting achievable and realistic goals is a crucial part of any self-evaluation. By outlining your ambitions, you communicate to your supervisors that you’re eager to progress and contribute to the organization’s success. Break down your goals into actionable steps and consider including timelines to make them more concrete and measurable.

If one of your goals is to improve your public speaking skills, you might include steps such as participating in meetings, volunteering for presentations, or attending workshops, with specific deadlines and milestones attached. This level of detail demonstrates your dedication to achieving your goals while providing a clear roadmap for your growth.

Strong Self-Evaluation: Providing Examples

Use specific instances.

When writing a self-evaluation, try to provide clear and specific examples from your work experience. By offering concrete instances, you help paint a more accurate picture of your achievements and progress. For instance, instead of saying, “I improved my communication skills,” you could say, “I successfully trained three new team members and presented our quarterly report to the management team.” Using detailed examples will make it easier for your supervisors to understand your accomplishments and appreciate your efforts.

Quantify Your Accomplishments

Wherever possible, try to quantify your achievements by using numbers, percentages, or any other measurable indicators. This can help make your successes more tangible and easier to understand. For example, you might mention that you increased sales by 20% in your department or that you completed a project two weeks ahead of schedule. Always aim to back up your statements with quantifiable information to support your claims and show your effectiveness in your role.

Highlight Your Progress

It’s important to focus on the progress you’ve made and the growth you’ve experienced in your role. Use the self-evaluation as an opportunity to reflect on your personal and professional development. For example, you could discuss how you learned a new software program that boosted your team’s productivity, or how you overcame struggles with time management by implementing new strategies. Emphasize not just your accomplishments but also the positive changes you’ve made for yourself and your team throughout the evaluation period. This will help demonstrate your dedication to growth and continuous improvement.

1. Project Management Skills: – Strong Self-Evaluation Example: “In my role as a project manager, I successfully led a team of 10 to deliver a complex software development project three weeks ahead of schedule. I attribute this accomplishment to my rigorous approach to project planning, where I meticulously outlined project phases, set realistic milestones, and conducted weekly check-ins with team members to gauge progress and address any roadblocks. My proactive communication strategy prevented delays and ensured that all team members were aligned with the project objectives.”

2. Customer Service Excellence: – Strong Self-Evaluation Example: “I have consistently maintained a customer satisfaction rating above 95% over the past year by employing an empathetic and solution-oriented approach to customer interactions. For instance, when a customer was frustrated with a delayed order, I took the initiative to not only expedite the shipping but also provided a discount on their next purchase. This resulted in a positive review and repeat business, demonstrating my commitment to going above and beyond to ensure customer satisfaction.”

3. Innovative Problem Solving: – Strong Self-Evaluation Example: “I identified a recurring bottleneck in our inventory management process that was causing shipment delays. By analyzing the workflow and collaborating with the logistics team, I designed a new inventory tracking system using a Kanban board that increased our efficiency by 30%. This initiative reduced average shipment times from 5 days to 3 days, significantly improving our order fulfillment rates.”

4. Effective Team Leadership: – Strong Self-Evaluation Example: “As the head of the marketing team, I led a campaign that resulted in a 20% increase in brand engagement. I achieved this by fostering a collaborative environment where each team member’s ideas were valued and incorporated. I organized brainstorming sessions that encouraged creative problem-solving and ensured that the team’s goals were aligned with the company’s vision. My leadership directly influenced the campaign’s success and the team’s high morale.”

5. Adaptability and Learning Agility: – Strong Self-Evaluation Example: “When our company transitioned to a new CRM system, I took the initiative to master the software ahead of the formal training. I then shared my knowledge with my colleagues through a series of workshops, which facilitated a smoother transition for the entire department. My ability to quickly adapt to new technology and willingness to assist others in their learning process demonstrates my dedication to continuous improvement and team success.”

Self-Evaluation Dos and Don’ts

Stay honest and constructive.

When writing a self-evaluation, it’s vital to be honest and realistic about your performance. Reflect on the achievements and challenges you’ve faced, and consider areas where you can improve. For example, if you struggled to complete a project on time, mention the obstacles you faced and the lessons you learned. This will show that you’re committed to personal growth and self-improvement.

I successfully completed seven out of eight projects within the given time frame. However, there were difficulties in delivering the last project on time due to a lack of resources. Moving forward, I plan to improve on allocating resources more effectively to ensure timely delivery.

Avoid Undermining Your Efforts

While it’s essential to view your performance objectively, don’t downplay your achievements or accomplishments. Acknowledge your efforts and reflect on your contributions to the team. For instance, if you’ve improved your sales numbers, highlight your success and outline the strategies you implemented to achieve this.

This quarter, my sales numbers increased by 15%, surpassing the target of 10%. I was persistent in following up on leads and implemented new techniques, such as personalized presentations, to connect with potential clients better.

Keep a Positive Outlook

Maintaining a positive attitude when discussing your performance is crucial in a self-evaluation. Focus on the progress you’ve made and show your willingness to learn from mistakes and challenges. Don’t dwell on the negatives; instead, frame them as opportunities for growth and learning, and share your plans for improvement.

While I encountered challenges in team communication earlier in the year, I have since taken steps to improve. I enrolled in a communication skills workshop, and the techniques I learned have helped me collaborate more effectively with my colleagues. I look forward to applying these skills to future projects.

Finalizing Your Self-Evaluation

Edit for clarity and concision.

After you’ve written your self-evaluation, take some time to review and edit it for clarity and concision. This means making sure that your points are expressed clearly, without ambiguity, and that you’ve removed any unnecessary or repetitive information. Here are some tips to help you do this:

- Use short sentences and active voice to make your points clear.

- Break up long paragraphs into smaller ones for easier reading.

- Double-check your spelling, grammar, and punctuation.

- Make sure that your points are stated in a logical and organized manner.

Request Peer Review

Once you’re satisfied with your self-evaluation, consider asking a trusted colleague or manager to review it. This can provide you with valuable feedback and help ensure that your evaluation is well-rounded, accurate, and unbiased. Keep these points in mind when requesting a peer review:

- Choose someone who knows your work well and has a clear understanding of your job responsibilities.

- Ask them to review your evaluation for clarity, accuracy, and comprehensiveness.

- Be open to constructive feedback, and make any necessary revisions based on their input.

By following these steps for finalizing your self-evaluation, you’ll have a stronger, more polished document that effectively highlights your accomplishments, areas for improvement, and goals for the future. This will provide a solid foundation for discussing your performance with your manager and creating a clear roadmap for professional growth.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are some helpful tips for writing an impactful self-evaluation.

When writing a self-evaluation, always be honest and specific about your accomplishments and goals. Provide examples and use metrics to quantify your achievements whenever possible. Reflect on areas where you can improve and create a plan for personal development. Use positive language, keep it concise and focused, and don’t forget to mention any feedback you’ve received from coworkers, clients, or managers.

Can you give examples of strong points to highlight in a self-evaluation?

Some powerful points you can emphasize in a self-evaluation include successful project management, exceeding targets or goals, implementing new processes that improve efficiency, demonstrating strong teamwork, and receiving positive client or coworker feedback. Tailor your examples to highlight your unique strengths and align with your role and company goals.

How would one describe their personal achievements in a self-assessment for a performance review?

To describe personal achievements effectively in a self-assessment, be results-oriented, and show the impact of your accomplishments. Use specific examples to illustrate your success and demonstrate how these achievements contributed to your team or company goals. If possible, quantify your results through metrics or figures to give a clear picture of your performance.

Could you provide a sample paragraph of a self-evaluation for a senior management position?

“Over the past year, as the Senior Manager of the (…) team, I have successfully launched three major projects that resulted in a 25% increase in revenue. My leadership style has fostered a collaborative environment, with my team consistently achieving all targets on time. I have also implemented training initiatives to develop team members’ skillsets, and our client satisfaction rate has increased by 15%. I plan to focus on further expanding our project portfolio and mentoring junior managers to strengthen the team’s leadership capabilities.”

What could be good sentence starters for framing self-evaluation points?

- During my time in this role, I have accomplished…

- One area I have excelled in is…

- An example of a significant contribution is…

- I demonstrated strong problem-solving skills when I…

- My collaboration with coworkers has led to…

- In terms of improvement, I plan to focus on…

- Over the past year, my growth has been evident in…

- Self Evaluation Examples [Complete Guide]

- 40 Competency Self-Evaluation Comments Examples

- 42 Adaptability Self Evaluation Comments Examples

- 30 Examples of Teamwork Self Evaluation Comments

- 45 Self Evaluation Sample Answers: Strengths and Weaknesses

- 45 Productivity Self Evaluation Comments Examples

How to Write a Self Evaluation (With Examples)

First step, be honest about your hits and misses.

Writing about yourself, especially if those words are going to be part of your permanent work record, can be daunting. But it doesn’t have to be. In fact, self evaluations give you a voice in your performance review , and they’re opportunities to outline your career goals and get help in reaching them.

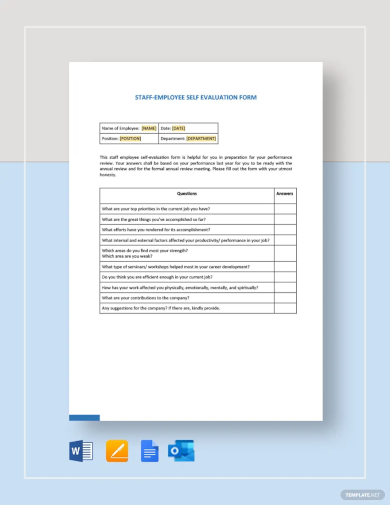

What Is a Self Evaluation?

Self evaluations are performance assessments that both employees and managers complete. They can be done quarterly, semi-annually or annually, and range from open-ended questions discussed to ratings given on a numeric scale.

Below, we’ll examine self evaluation benefits, tips and examples, plus how both employees and managers can complete them successfully.

A self evaluation , sometimes called a self-assessment performance review, is a time where you and your manager get together to rate your performance over a given time span, either using a numerical scale or by answering open-ended questions. You complete the evaluation and so does your manager. During the performance review , the two of you compare notes to arrive at a final evaluation.

Benefits of Self Evaluations

1. help employees and managers prepare for performance reviews.

Completing a self evaluation can help guide the eventual performance-review conversation in a structured, but meaningful, way. It also helps both parties get an idea of what needs to be discussed during a performance review, so neither feels caught off guard by the conversation.

2. Give Employees an Opportunity to Reflect on Their Progress

Since self evaluations are inherently reflective, they allow employees to identify and examine their strengths and weaknesses. This helps employees both know their worth to an organization and what they still have left to learn.

“Self evaluations enable employees to see their work in its entirety,” Jill Bowman, director of people at fintech company Octane , told Built In. “They ensure that employees reflect on their high points throughout the entire year and to assess their progress towards achieving predetermined objectives and goals.”

3. Help Managers Track Employee Accomplishments

Employee self assessments help managers more accurately remember each employee’s accomplishments. “As many managers often have numerous direct reports, it provides a useful summary of the achievements of each member,” Bowman said.

4. Improve Employee Satisfaction

Academic literature indicates that employees are more satisfied with evaluations that involve two-way communication and encourage a conversation between manager and employee, according to Thomas Begley, professor of management at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute .

The thing is, employees have to trust that the process is fair, Begley told Built In. If they believe it is, and they’re treated fairly and respectfully during the process, employees react positively to self evaluations.

5. Can Decrease Employee Turnover

Some companies see tangible results from self evaluations. For example, Smarty , an address-verification company, enjoys low staff turnover, said Rob Green, chief revenue officer. The self-evaluation method, coupled with a strong focus on a communication-based corporate culture, has resulted in a 97 percent retention rate, Green told Built In.

Related How to Be More Confident in Performance Reviews

How to Write a Self Evaluation

The ability to write a solid self evaluation is a critical career skill.

“Self evaluations give you a platform to influence your manager and in many cases, reframe the nature of the relationship with your manager,” Richard Hawkes, CEO and founder of Growth River , a leadership and management consulting company, told Built In. “And all results in business happen in the context of relationships.”

Below are some tips on how to complete a self evaluation.

1. Track Your Work and Accomplishments

Daily or weekly tracking of your work can help you keep track of your progress and also prevent last-minute panic at performance evaluation time, said Peter Griscom, CEO at Tradefluence . “Strip down the questions to two or three, and just ask yourself, ‘How well did I communicate today?’ ‘How well did I solve problems today?’ ‘What have I achieved today?’” Griscom told Built In. “Get in the habit of writing those things out and keeping track and over time.”

2. Answer Honestly

For his first self evaluation, Griscom remembers wondering how to best answer the questions. After he asked his manager for guidance, Griscom answered the questions as accurately as he could. “What came out of it was really valuable, because it gave me a chance to reflect on my own achievements and think about where I can improve,” he said. “It forced me to do the thinking instead of just accepting feedback.”

3. Highlight Your Achievements

If your boss has a handful of direct reports, chances are good they haven’t noticed each of your shining moments during a review period. This is your chance to spotlight yourself. Quotas exceeded, projects finished ahead of schedule, fruitful mentoring relationships, processes streamlined — whatever you’ve done, share it, and don’t be shy about it, said Alexandra Phillips , a leadership and management coach. Women, especially, tend not to share achievements and accomplishments as loudly or often as they should. “Make sure your manager has a good sense of where you’ve had those wins, large and small, because sometimes they can fly under the radar,” Phillips told Built In.

4. Admit Weaknesses and How You Have Grown

If you’ve made a whopper mistake since your past review, mention it — and be sure to discuss what you’ve learned from it. Chances are good your manager knows you made a mistake, and bringing it up gives you the opportunity to provide more context to the situation.

5. Acknowledge Areas of Improvement

Be prepared for your manager to point out a few areas for improvement. This is where career growth happens. “If you want something,” whether it’s a promotion or move to another department, “you need to know how to get there,” Phillips said.

More on Self Evaluations Self-Evaluations Make Stronger Leaders. Here’s How to Write One.

Self Evaluation Examples and Templates Answers

Still not sure what to do when you put pen to paper? Here are six open-ended self evaluation sample questions from the Society for Human Resource Management, as well as example answers you can use to prepare for your own self evaluation.

1. Job Performance Examples

List your most significant accomplishments or contributions since last year. How do these achievements align with the goals/objectives outlined in your last review?

How to answer with positive results:

In the past year, I successfully led our team in finishing [project A]. I was instrumental in finding solutions to several project challenges, among them [X, Y and Z]. When Tom left the company unexpectedly, I was able to cover his basic tasks until a replacement was hired, thus keeping our team on track to meet KPIs. I feel the above accomplishments demonstrate that I have taken more of a leadership role in our department, a move that we discussed during my last performance review.

How to answer with ways to improve:

Although I didn’t meet all of my goals in the last year, I am working on improving this by changing my workflow and holding myself accountable. I am currently working to meet my goals by doing [X, Y and Z] and I plan to have [project A] completed by [steps here]. I believe that I will be able to correct my performance through these actionable steps.

Describe areas you feel require improvement in terms of your professional capabilities. List the steps you plan to take and/or the resources you need to accomplish this.

I feel I could do better at moving projects off my desk and on to the next person without overthinking them or sweating details that are not mine to sweat; in this regard I could trust my teammates more. I plan to enlist your help with this and ask for a weekly 15-minute one-on-one meeting to do so.

Identify two career goals for the coming year and indicate how you plan to accomplish them.

One is a promotion to senior project manager, which I plan to reach by continuing to show leadership skills on the team. Another is that I’d like to be seen as a real resource for the organization, and plan to volunteer for the committee to update the standards and practices handbook.

2. Leadership Examples

Since the last appraisal period, have you successfully performed any new tasks or additional duties outside the scope of your regular responsibilities? If so, please specify.

Yes. I have established mentoring relationships with one of the younger members of our team, as well as with a more seasoned person in another department. I have also successfully taken over the monthly all-hands meeting in our team, trimming meeting time to 30 minutes from an hour and establishing clear agendas and expectations for each meeting. Again, I feel these align with my goal to become more of a leader.

Since the last review period, I focused my efforts on improving my communication with our team, meeting my goals consistently and fostering relationships with leaders in other departments. Over the next six months, I plan on breaking out of my comfort zone by accomplishing [X, Y and Z].

What activities have you initiated, or actively participated in, to encourage camaraderie and teamwork within your group and/or office? What was the result?

I launched a program to help on-site and remote colleagues make Mondays more productive. The initiative includes segmenting the day into 25-minute parts to answer emails, get caught up on direct messages, sketch out to-do lists and otherwise plan for the week ahead. The result overall for the initiative is more of the team signs on to direct messages earlier in the day, on average 9:15 a.m. instead of the previous 10 a.m., and anecdotally, the team seems more enthusiastic about the week. I plan to conduct a survey later this month to get team input on how we can change up the initiative.

Although I haven’t had the chance to lead any new initiatives since I got hired, I recently had an idea for [A] and wanted to run it by you. Do you think this would be beneficial to our team? I would love to take charge of a program like this.

3. Professional Development Examples

Describe your professional development activities since last year, such as offsite seminars/classes (specify if self-directed or required by your supervisor), onsite training, peer training, management coaching or mentoring, on-the-job experience, exposure to challenging projects, other—please describe.

I completed a class on SEO best practices and shared what I learned from the seminar during a lunch-and-learn with my teammates. I took on a pro-bono website development project for a local nonprofit, which gave me a new look at website challenges for different types of organizations. I also, as mentioned above, started two new mentoring relationships.

This is something I have been thinking about but would like a little guidance with. I would love to hear what others have done in the past to help me find my footing. I am eager to learn more about [A] and [B] and would like to hear your thoughts on which courses or seminars you might recommend.

Types of Self Evaluations

Self evaluations can include rating scale questions, open-ended questions or a hybrid of both. Each approach has its own set of pros and cons to consider.

1. Rating Self Evaluation

Rating scale self evaluations give a list of statements where employees are asked to rate themselves on a scale of one to five or one to ten (generally the higher the number, the more favorable the rating).

For example, in Smarty’s self evaluations, it uses a tool called 3A+. This one calls for employees and managers to sit down and complete the evaluation together, at the same time. Employees rate themselves from 3, 2 or 1 (three being the best) on their capability in their role; A, B or C on their helpfulness to others, and plus or minus on their “diligence and focus” in their role. Managers rate the employees using the same scale. A “perfect” score would be 3A+, while an underperforming employee would rate 2B-.

At the performance evaluation meeting, managers and employees compare their ratings, and employees ask for feedback on how they can improve.

But rating systems can have their challenges that are often rooted in bias . For example, women are more likely to rate themselves lower than men. People from individualistic cultures, which emphasize individuals over community, will rate themselves higher than people from collectivist cultures, which place a premium on the group rather than the individual.

2. Open-Ended Question Self Evaluation

Open-ended questions ask employees to list their accomplishments, setbacks and goals in writing. The goal of open-ended questions is to get employees thinking deeply about their work and where they need to improve.

Open-ended questions allow employees a true voice in the process, whereas “self ratings” can sometimes be unfair , Fresia Jackson, lead research people scientist at Culture Amp , told Built In.

With open-ended questions, employees tend to be more forgiving with themselves, which can be both good and bad. Whatever result open ended questions bring about, they typically offer more fodder for discussion between employees and managers.

3. Hybrid Self Evaluation

Hybrid self evaluations combine both rating questions and open-ended questions, where employees assess their skills and accomplishments by using a number scale and by answering in writing. This type of self evaluation lets employees provide quantitative and qualitative answers for a more holistic reflection.

Self-Evaluation Questions for Performance Reviews

If you’ve never done a self evaluation, or if you just need a refresher before your next performance review, looking over some examples of self evaluation questions — like the ones below — can be a helpful starting point.

Common Self-Evaluation Questions for Performance Reviews

- What are you most proud of?

- What would you do differently?

- How have you carried out the company’s mission statement?

- Where would you like to be a year from now?

- List your skills and positive attributes.

- List your accomplishments, especially those that impacted others or moved you toward goals.

- Think about your mistakes and what you’ve learned from them.

- What are your opportunities to grow through advancement and/or learning?

- How do the above tie to your professional goals?

Self-Evaluation Questions for Career Planning and Growth

- What are you interested in working on?

- What are you working on now?

- What do you want to learn more about?

- How can I as your manager better support you?

- What can the company do to support your journey?

- How can the immediate team support you?

- What can you do to better support the team and the company?

Self-Evaluation Questions for Performance and Career Goals

- How did you perform in relation to your goals?

- What level of positive impact did your performance have on the team?

- Did your performance have a positive impact on the business?

- What was your level of collaboration with other departments?

- What corporate value do you bring to life?

- What corporate value do you most struggle to align with?

- Summarize your strengths.

- Summarize your development areas.

- Summarize your performance/achievements during this year.

- How would you rate your overall performance this year?

Related How to Set Professional Goals

How Should Managers Approach Self Evaluations?

It’s clear here that self evaluations, as a type of performance review, are more employee- than manager-driven. That said, managers are a key ingredient in this process, and the way managers handle self evaluations determines much about how useful they are and how well employees respond to them. To make sure they’re as effective as possible, consider these suggestions.

Train Managers on How to Use Evaluations

“If you don’t, there’s no point in doing them, because the manager is going to be the one driving the conversations,” Elisabeth Duncan, vice president of human resources at Evive, said. “Without training, the [evaluations] will be a checkbox and not meaningful.”

Don’t Use Ratings Formulaically

The results of self evaluations that employ a scale (say, one to five) can vary wildly, as one manager’s three is another manager’s five. Use the scale to identify and address discrepancies between the manager’s and employee’s answers, not to decide on raises or promotions across the company.

Hold Self Evaluations Often

They work best as career-development tools if they’re held semi-annually, quarterly or even more often. “It’s about an ongoing, consistent conversation,” Duncan said.

Tailor Them For Each Department

Competencies in sales very likely differ from competencies in tech, marketing and other departments. Competencies for junior-level employees probably differ wildly from those for senior managers. Self evaluations tailored to different employee populations will be more effective, and fairer.

Stress That the Rating Is Just the Start

The rating or the open-ended questions are the beginning of the evaluation process; they are not the process itself. “These are tools to trigger a conversation,” Duncan said.

Overall, think of self evaluations as a way to engage with your manager and your work in a way that furthers your career. Embrace the self evaluation and get good at writing them. In no time at all, you’ll find that they can be a productive way to reflect on yourself and your skillset.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a self evaluation.

A self evaluation is a personal assessment used for employees to reflect on their strengths, weaknesses, accomplishments and overall progress during an allotted time on the job.

Self evaluations are often completed quarterly, semi-annually or annually, and can include numbered rating questions or open-ended written questions.

How do you write a good self evaluation?

An effective self evaluation is one where you highlight your achievements and instances of growth as well as areas for improvement during your given period of time at work. Tracking specific accomplishments and metrics can be especially helpful for writing a good self evaluation.

Recent Career Development Articles

Ultimate Guide to Writing a Self-Evaluation Essay

Self-evaluation essays are a type of writing assignment that asks people to think about their own skills, accomplishments, and performance. The goal of a self-evaluation essay is to give a full picture of one’s own strengths and weaknesses so that areas for improvement can be found and goals for personal and professional growth can be set.

Self-evaluation essays are an important part of both personal and professional growth. They give people a chance to think about how they’ve done and set goals for the future . By thinking about themselves, people can learn more about their strengths and weaknesses and make a plan for continuing to grow and get better.

In this complete guide to writing a self-evaluation essay, we’ll look at the most important parts , such as planning, writing, and editing. We’ll also give you advice on how to come up with ideas and organize them, as well as how to think about your own performance and what you’ve done well. By the end of this guide, readers will have the skills and knowledge they need to write effective and meaningful self-evaluation essays in a variety of situations.

What You'll Learn

Elements of a Self Evaluation Essay

A self evaluation essay typically includes the following elements:

1. The purpose of a self evaluation essay: The goal of a self-evaluation essay is to give a full picture of your skills, accomplishments, and areas where you can improve. In the essay, you should be honest and thoughtful about your own performance and set goals for personal and professional growth.

2. Reflection and self-assessment: A self evaluation essay requires individuals to reflect on their own performance and accomplishments. This may include reflecting on past experiences , identifying areas for improvement, and setting goals for the future.

3. Identification of strengths and weaknesses: In a self-evaluation essay, it’s important to talk about both your strengths and weaknesses. This could mean talking about what has been done well and what needs to be improved.

4. Goals and objectives for personal growth: In a self-evaluation essay, you should list specific goals and objectives for your own and your career’s growth. This could mean setting goals to improve skills, move up in your career, or take care of your own health .

5. Evidence and examples to support claims: The claims in a self-evaluation essay should be backed up by evidence and examples. This can include specific examples of accomplishments, feedback from others, or data to back up claims about skills or accomplishments.

Preparing to Write a Self Evaluation Essay

Before you start writing a self-evaluation essay, you should prepare by gathering information and evidence, coming up with ideas, and writing down your goals and objectives. Here are some tips for getting ready to write an essay about yourself:

1. Gathering information and evidence: Before you start writing, make sure you have all the information or proof you need to back up your claims. This could be your past performance reviews, comments from coworkers, or information about what you’ve done.

2. Brainstorming and outlining: Before you start writing, give yourself time to think of ideas and put them in order. Make a plan that includes the most important parts of a self-evaluation essay, such as reflection, identifying your strengths and weaknesses, and setting goals for your own growth.

3. Identifying goals and objectives: Before you start writing, you should set specific goals for your personal and professional growth. This could mean setting goals to improve skills, move up in your career, or take care of your own health.

4. Choosing a format and structure: Choose how your self-evaluation essay will look and be put together. This could mean choosing a chronological or thematic approach, or using a certain format or template.

By taking the time to prepare and gather information, individuals can write more effective and meaningful self evaluation essays that accurately reflect their own performance and accomplishments.

Writing a Self Evaluation Essay

When writing a self evaluation essay , it is important to follow a clear structure that includes an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. The following tips can help you to write an effective self evaluation essay:

1. Introduction: Begin with a hook that grabs the reader’s attention and provides context for the essay . Introduce the purpose of the essay and provide a thesis statement that summarizes your main argument.

2. Body paragraphs: The body of the essay should include several paragraphs that address different aspects of your performance, skills, and accomplishments. Use specific examples and evidence to support your claims and provide a clear and detailed reflection on your own performance.

3. Conclusion: Summarize your main points and restate your thesis statement. End with a statement that reflects on what you have learned from the self evaluation process and outlines your goals for personal and professional growth.

4. Tone and style: Use a professional and objective tone when writing a self evaluation essay. Avoid using overly emotional or defensive language, and focus on providing an honest and thoughtful reflection on your own performance.

5. Grammar and mechanics: Pay careful attention to grammar, mechanics, and spelling when writing a self evaluation essay. Use clear and concise language, and proofread your essay carefully to ensure that it is error-free.

Self Evaluation Essay Examples

To better understand how to write a self evaluation essay, it can be helpful to examine examples of effective essays . Here are some key takeaways from successfulself evaluation essays:

1. Sample self evaluation essay: A sample self evaluation essay can provide a helpful template for structuring your own essay. Look for essays that focus on specific goals or accomplishments, and use them as a guide for organizing your own essay.

2. Analysis of effective self evaluation essays: Analyze effective self evaluation essays to identify the key elements that make them successful. Look for essays that provide specific examples and evidence to support claims , and that offer a clear and honest reflection on strengths and weaknesses.

3. Key takeaways from successful self evaluation essays : Successful self evaluation essays typically include a clear and well-structured introduction, detailed body paragraphs that provide specific examples and evidence, and a thoughtful conclusion that reflects on what has been learned and sets goals for future growth.

By studying examples of effective self evaluation essays and applying the tips and strategies outlined in this guide, individuals can write more effective and meaningful self evaluation essays that accurately reflect their own performance, skills, and accomplishments.

Self Evaluation Essay Topics

When choosing a topic for a self evaluation essay , consider areas where you have experienced personal growth, challenges, or accomplishments. Here are some potential topics to consider:

1. Personal achievements and challenges: Write about a personal achievement or challenge that you have experienced, and reflect on what you learned from the experience.

2. Educational and career goals: Write about your educational or career goals, and reflect on the progress you have made toward achieving them.

3. Personal growth and development: Write about a specific area where you have experienced personal growth and development, such as communication skills or leadership abilities.

4. Strengths and weaknesses: Write about your strengths and weaknesses, and reflect on how they have impacted your personal and professional life.

5. Critical reflection on experiences: Write about a specific experience that has had a significant impact on your life, and reflect on what you have learned from the experience.

Self Evaluation Essay Outline

A clear and well-organized outline is essential for writing an effective self evaluation essay . Here are some tips for creating an effective outline:

1. Basic outline structure: Your outline should include an introduction, several body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

2. Tips for creating an effective outline: Start by brainstorming and organizing your thoughts into a logical sequence. Use bullet points or short phrases to outline the key ideas in each section of your essay . Make sure that your outline includes specific examples and evidence to support your claims.

3. Examples of selfevaluation essay outlines: Here is an example of a basic outline structure for a self evaluation essay:

I. Introduction

A. Hook

B. Context

C. Thesis statement

II. Body Paragraphs

A. Reflection on personal achievements and challenges

1. Examples and evidence to support claims

2. Reflection on what was learned

B. Discussion of educational and career goals

1. Progress made toward achieving goals

2. Reflection on areas for improvement

C. Analysis of personal growth and development

1. Specific areas of growth

2. Reflection on how growth has impacted personal and professional life

D. Identification of strengths and weaknesses

1. Discussion of strengths and how they have contributed to success

2. Discussion of weaknesses and how they have been addressed

E. Critical reflection on experiences

1. Discussion of a specific experience

2. Reflection on what was learned from the experience

III. Conclusion

A. Summary of main points

B. Reflection on what was learned from the self evaluation process

C. Goals for personal and professional growth

By following a clear and well-organized outline, individuals can write more effective and meaningful self evaluation essays that accurately reflect their own performance, skills, and accomplishments.

Self Evaluation Essay Thesis

An important part of a self-evaluation essay is a thesis statement. It gives a clear and concise summary of the main point or argument of the essay and helps the reader figure out what to do with the rest of the essay. Here are some tips for writing a strong thesis statement for a self-evaluation essay:

1. Purpose and importance of a thesis statement : The purpose of a thesis statement is to provide a roadmap for the rest of the essay. It should convey the main argument or focus of the essay , and provide a clear and concise summary of the key points that will be discussed.

2. Tips for crafting a strong thesis statement: To craft a strong thesis statement, start by brainstorming and organizing your thoughts. Identify the key themes or ideas that will be discussed in the essay , and use these to craft a clear and concise thesis statement. Make sure that your thesis statement is specific, focused, and relevant to the topic of the essay .

3. Examples of effective self evaluation essay thesis: Here are some examples of effective thesis statements for self evaluation essays:

– “Through reflecting on my personal achievements and challenges, I have gained a deeper understanding of my own strengths and weaknesses, and have identified opportunities for personal and professional growth.”

– “My educational and career goals have been shaped by my experiences and accomplishments, and I am committed to continuing to develop my skills and knowledge in order to achieve these goals.

– “Through engaging in critical reflection on my experiences, Ihave gained a greater appreciation for the value of personal growth and development, and have identified specific areas where I can continue to improve.”

Self Evaluation Essay Structure

A successful self evaluation essay should follow a clear and well-structured format. Here are some tips for structuring a successful self evaluation essay:

1. Introduction: The introduction should include a hook that grabs the reader’s attention, provide context for the essay, and include a clear and concise thesis statement that summarizes the main argument or focus of the essay .

2. Body paragraphs: The body of the essay should include several paragraphs that address different aspects of your performance, skills, and accomplishments. Use specific examples and evidence to support your claims, and provide a clear and detailed reflection on your own performance.

3. Conclusion: The conclusion should summarize the main points of the essay , restate the thesis statement, and provide a thoughtful reflection on what has been learned from the self evaluation process. It should also include goals for personal and professional growth.

4. Tips for structuring a successful self evaluation essay: To structure a successful self evaluation essay, organize your thoughts into a clear and logical sequence. Use specific examples and evidence to support your claims, and make sure that each paragraph focuses on a specific aspect of your performance or experience. Use transitions to connect ideas and ensure that the essay flows smoothly.

By following these tips and structuring your self evaluation essay in a clear and well-organized format, you can write an effective and meaningful essay that accuratelyreflects your own performance and accomplishments.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. what is a self evaluation essay.

A self-evaluation essay is a piece of writing in which the writer thinks about their own skills, accomplishments, and performance. The goal of a self-evaluation essay is to give a full picture of one’s own strengths and weaknesses so that areas for improvement can be found and goals for personal and professional growth can be set.

2. What are the elements of a self evaluation essay?

A self-evaluation essay usually includes reflection and self-assessment, identification of strengths and weaknesses, goals and objectives for personal growth, evidence and examples to support claims, and a clear and well-organized structure.

3. How do I choose a topic for a self evaluation essay?

When choosing a topic for a self-evaluation essay, think about areas in which you’ve grown, faced challenges, or done well. Personal successes and problems, educational and career goals, personal growth and development, strengths and weaknesses, and a critical look back on experiences are all possible topics .

4. How do I structure a self evaluation essay?

The format of a self-evaluation essay should be clear and well-structured, with an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. The introduction should have a hook, set the scene for the essay , and have a clear statement of the essay’s main point. The body of the essay should have several paragraphs that talk about different parts of your performance, skills, and accomplishments. The conclusion should summarize the main points of the essay and give goals for personal and professional growth.

5. What are some tips for writing a successful self evaluation essay?

Some tips for writing a good self-evaluation essay include gathering information and evidence, coming up with ideas and making an outline, identifying goals and objectives, using a professional and objective tone, paying attention to grammar and mechanics, and using specific examples and evidence to support claims.

Writing a self-evaluation essay can help you improve as a person and as a worker. By thinking about your own performance, skills, and accomplishments, you can learn more about your strengths and weaknesses and set goals for continuing to grow and get better. To write a good self-evaluation essay, you should stick to a clear and well-organized structure, use a professional and objective tone, and back up your claims with specific examples and evidence.

Start by filling this short order form order.studyinghq.com

And then follow the progressive flow.

Having an issue, chat with us here

Cathy, CS.

New Concept ? Let a subject expert write your paper for You

Post navigation

Previous post.

📕 Studying HQ

Typically replies within minutes

Hey! 👋 Need help with an assignment?

🟢 Online | Privacy policy

WhatsApp us

How to Write an Effective Self-Assessment

by Marlo Lyons

Summary .

Writing a self-assessment can feel like an afterthought, but it’s a critical part of your overall performance review. Managers with many direct reports likely won’t have visibility into or remember all of your notable accomplishments from the year, and they don’t have time to read a long recap. The author offers five steps for drafting a self-assessment that covers your most impactful accomplishments and demonstrates self-awareness through a lens of improvement and development: 1) Focus on the entire year; 2) consider company and functional goals; 3) look for alignment with those goals; 4) seek feedback from colleagues; and 5) draft a concise list of accomplishments.

It’s performance review season for many companies, which means it’s time to reflect on the year and draft a self-assessment of your accomplishments. Writing an impactful self-assessment will set the tone for your manager’s evaluation of your work, which can affect your compensation (e.g., merit increase, bonus, etc.).

Partner Center

15 Self-Assessment Examples for Students

Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

Self-assessment is when we analyze our own behavior. It is a way for us to understand how we are doing at something.

People who self-assess will examine their current level of performance on a given dimension in order to see how they can improve.

We can compare our performance to a known standard or our own set of goals. That evaluation will enable us to identify our strengths and weaknesses, and help us chart a path of progress.

Self-assessment can be applied in just about any context. For example, we can assess our level of fitness, how we perform during a job interview, or if we are easy to work with, or not.

Definition of Self-Assessment

Brown and Harris (2013, p. 368) defined self-assessment in a school context as a “descriptive and evaluative act carried out by the student concerning his or her own work and academic abilities” .

Making a judgment regarding our own abilities is easier said than done. If we want to know the truth, then we need an objective assessment.

That’s not easy to do when it comes to our own performance, because:

- Some people may have a positive bias about their abilities and give themselves high ratings when that might not be deserved.

- Other people are very critical of themselves and may be overly harsh.

Ideally, evaluations should come from professionals with a lot of training and experience. However, that’s not always convenient and it can also be expensive. So, although self-assessments are not ideal, they are very practical.

Student Self-Assessment Examples

1. keeping a diary.

If you’re not sure how to self-assess, the first step could be to keep a diary of what you’ve been doing. This is a form of personal reflection that allows you to pause and assess your progress.

There are also some great self-assessment diaries out there, such as the various reflective teaching diaries, that provide prompting questions such as “what is your mood right now?” and “what’s something you did that you were proud of today?”

These moments of self-reflection also act as moments of self-assessment . While you reflect, you also pause to assess your actions and what you could have done differently to change outcomes next time. In this process, you can learn to more effectively self-regulate and incrementally improve.

2. Self-Reflection After a Meeting

None of us want to be labeled as “difficult” or “lazy”. So, after a meeting, it is a good idea to take a few moments and reflect on how we did. Were we attentive? Did we participate enough, or did we talk too much? Were we argumentative and unreasonable, or did we make constructive comments?

One of the most difficult challenges of work is getting along with colleagues. Everyone has an opinion, and everyone wants to pursue their own agenda.

In addition to that, everyone has a different personality. Some of those personalities might be difficult to deal with, day in and day out.

So, understanding how we are to work with is important.

Work consumes most of our lives. Having a successful career is essential to so many other aspects of our happiness. Therefore, reflecting on how we act in meetings can go a long way to helping us be more respectful and conciliatory.

See More: Self-Reflection Examples

3. Recording Your Presentation at Work

One form of self-assessment that can be extremely valuable is to record our presentations. It can be a sales pitch or product proposal, or just about anything else. There is probably no better way to evaluate our performance than recording it.

We can make observations about our intonation and rate of speech, in addition to our posture and any odd mannerisms we might exhibit. Of course, we can ask a trusted colleague to watch and give us a few insights as well.

Surprisingly, based on some research findings, there may not always be agreement between our self-assessment and what our peers think (Campbell et al., 2001).

4. Filming your Sports Performance

In the same way that you can record a business presentation, you can also record yourself participating in sports to watch it back.

In fact, professional sportspeople and their coaches like tennis players, football players, and baseball batters will all film themselves to see how they performed.

They might be looking at their stance in tennis to see if they’ve got the right posture. In baseball, they may be looking at the position of the shoulders and elbows when the batter swings his bat. These observations can help shape a sportsperson’s self-concept so they have a realistic idea of their abilities.

By watching their actions, the sportspeople can assess their own actions and see themselves from a new perspective. It gives them the opportunity to see things about their actions that they couldn’t see in the moment.

5. Tracking Your Gym Workouts

Recording your daily workouts at the gym is another form of self-assessment. This will help you assess your current status and also help you become aware of your rate of progress.

Back in the old days, people used to carry clipboards around with them at the gym. After finishing each set, they would write down how much weight they lifted and the number of reps. It was also a good excuse to take a breather.

Of course, in this century, there’s an APP for that. Instead of using a paper worksheet and wooden pencil that was made by killing trees and destroys the environment, you can use an electronic version on your smartphone that was made with rare earth minerals and child labor.

6. Tracking Personal Growth

Personal growth is a long-term process. The goal is to make continuous progress over time. That can mean months or even years.

Over time, we can continuously make improvements in our sense of well-being, state of mind, or even our spirituality.

Assessing your personal growth can be on any dimension of life you want. It can be about our sense of well-being, our level of knowledge, level of spirituality, or anything else that is deeply important to you.

First, you determine where you are now and where you want to be in the future. This will help you identify your goals and set targets. Make sure that your targets are realistic and feasible, and phrased in a way that is measurable. For example, don’t just say that you “want to learn more about history.” Instead, say that your goal is to take a university course or read two books on the Roman Empire.

Phrasing your personal growth goal in a concrete manner makes them easy to determine if they have been accomplished or not. Furthermore, when they are accomplished, you can see it, and this will help you build your own self-efficacy .

7. Using a Fitness App

There are so many fitness apps available today that you can find one, or a couple thousand, that will suit your needs just fine.

Generally speaking, these apps fall into one of three categories: nutrition, workout, and activity.

These apps will allow you to become more aware of your nutritional intake, chart your progress at the gym, or record how long and how far you walk or run. Fitness apps are a great way to assess if you are making progress on any of these health dimensions, or if you are just maintaining the status quo .

It’s an example of elf-assessment in the palm of your hand.

8. Participating in a Mock Job Interview

Before going into a job interview, people will often practice in a mock interview to self-assess their performance in order to improve before the big event!

Job interviews can be a bit stressful. There is a lot riding on your performance, especially if it is for a job that you really want. Plus, you only have one shot. If you fail the first interview, you will not get called back for another.

Many universities have career centers that offer students an opportunity to receive valuable coaching regarding their job interview performance. This involves going through a mock interview with an experienced professional.

Afterward, the coach and student will discuss the results together. Participating in a mock interview is a fantastic way to assess your strengths and weaknesses, and just might help you land a great job.

9. Comparing Your Work with Others

One of the best ways to know how good you are is by comparing your performance with others. This is a kind of self-assessment by way of social comparison.

For example, after spending a ton of time on an essay, it is easy to be so immersed in it that you lose objectivity. You may think that you have really nailed it. However, instead of waiting to get the essay back from your teacher, it is a good idea to see an example of a paper that was already completed and evaluated as being very good.

You can then compare and contrast that essay with yours . Maybe the literature review in the really good essay went into much more detail than you thought was necessary. Or, maybe it contained charts and graphs that yours did not.

This form of self-assessment can be very informative.

10. Hiring a Life Coach

A life coach is an expert on helping people get the most out of their lives. A life coach can help someone improve their career, romantic relationship, or even offer advice on how to handle day-do-day affairs.

Every life coach is different, but generally speaking they will construct a very holistic assessment of a client by conducting in-depth conversations with them and maybe even make direct observations over an extended period of time. This will give them enough information to make suggestions and provide guidance. They will even take their services one step further and help the client implement those changes.

So, if you are looking for a comprehensive assessment of your life, something that is also very practical and forward-looking, then a life coach may be exactly what you need.

11. Career Aptitude Test

A career aptitude test is a simple questionnaire that asks about your interests, values, skills, and personality characteristics. It then uses that data to identify different careers that would be a good match to your profile.

It is a great self-assessment tool that can offer some career guidance. You can discover which professions are most suited to your unique profile. The results can be surprising. You just might discover that people like you do very well in a certain job you would have never considered before.

These sorts of self-assessments are often given to students graduating from high school. High school students are at a phase in their life where a decision about what sort of career they want to do is at the front of mind. So, it’s the perfect time to take one of these tests.

12. Taking the Big Five Personality Traits Inventory

A personality trait is a consistent way that a person acts and feels. The Big Five personality traits are considered to be the most commonly occurring. They consist of: extroversion, agreeableness, openness, conscientiousness , and neuroticism. Everyone has these 5 traits to one degree or another.

Research has investigated how these traits relate to an incredibly wide range of subject matter, from leadership style to quality of romantic relationships and everything in between. Not only are the Big Five consistent across diverse cultures, but they have considerable stability across the lifespan as well (Rantanen et al., 2007).

Fortunately, there are many versions of this inventory available online. Most have reasonable reliability and validity. So, if you wish to conduct a personality self-assessment, there are many options to choose from.

13. Using a Wellness Wheel

A Wellness Wheel is a form of self-assessment that examines all aspects of our life. Most wheels include seven dimensions: spiritual, emotional, professional, intellectual, social, physical, and environmental.

Wellness wheels are very popular because they can provide a snapshot of our current status from a broad perspective.

By examining the status of our life on these seven dimensions, we can increase our self-awareness . If that analysis leads to the conclusion that we need change, then the wellness wheel will show us wear to focus most of our effort.

The Wellness Wheel is an example of a very holistic approach to self-assessment. It doesn’t require a trained professional either, and many versions are available online.

14. Metacognitive Strategies

Metacognition refers to the act of thinking about thinking. It requires you to reflect on how you went about a task and identify pros, cons, and alternatives to the way you went about the task.

For example, if you had just had an argument with a friend, metacognition might involve reflecting on how you lost your cool and started saying things you regretted. You can think about why you followed that thought path, and how you might have been able to de-fuse the situation in the future.

Another example is reflecting on your own learning style. You may have tried to study for a test using reading, leading to a poor test score. Upon reflection, you may realize you were getting very tired when reading; and as a result, next time you are going to try to study by watching lecture videos instead of reading.

15. Taking a Myers-Briggs Test

A Myers-Briggs test is a personality test that can help you to understand your own personality and the personalities of others.

The test assesses you against 16 different personality types, and each type has its own strengths and weaknesses.

The Myers-Briggs test can help you to find out your own personality type, and it can also be used to improve communication and team work by understanding the different strengths and weaknesses of each personality type.

Thus, while the tool is doing the assessment, by self-administering this test, you’re actually self-evaluating in order to learn more about yourself and how you interact with the people around you.

Self-assessment can help us get a better handle on where we are in life or in our profession. Examining our status quo can help us identify our strengths and the areas that we should try to improve.

Self-assessment comes in many forms. It can include modern technology such as fitness apps, or old-school tech like making a video recording. There are also forms that don’t involve any technology at all. Hiring a real live person to be your life coach may be a bit pricey, but it is a long-term strategy that can be personal and totally centered on your needs.

No matter your preference or goals, there are many self-assessment methods available.

Andrade HL (2019) A Critical Review of Research on Student Self-Assessment. Frontiers in Education, 4(87). https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2019.00087

Brown, G. T., and Harris, L. R. (2013). Student self-assessment. In J. H. McMillan (Ed.), Sage Handbook of Research on Classroom Assessment , pp. 367-393. Los Angeles, CA: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452218649.n21

Campbell, K. S., Mothersbaugh, D. L., Brammer, C., & Taylor, T. (2001). Peer versus self- assessment of oral business presentation performance. Business Communication Quarterly , 64 (3). https://doi.org/10.1177/108056990106400303

John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big-Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (Vol. 2, pp. 102–138). New York: Guilford Press.

Muntaner-Mas, A., Martinez-Nicolas, A., Lavie, C.J. et al. (2019). A systematic review of fitness apps and their potential clinical and sports utility for objective and remote assessment of cardiorespiratory fitness. Sports Medicine, 49 , 587–600. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01084-y

Rantanen, J., Metsäpelto, R. L., Feldt, T., Pulkkinen, L. E. A., & Kokko, K. (2007). Long‐term stability in the Big Five personality traits in adulthood. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology , 48 (6), 511-518. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00609.x

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 18 Adaptive Behavior Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Ableism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Tips for Writing a Strong Self-Evaluation (With Examples)

Self-evaluations ask employees to reflect on (and often rate) their own performance over a set period of time.

While that sounds simple enough, it’s no secret that the self-assessment performance review process can be awkward. Singing our own praises may make our toes curl — and acknowledging where we’ve made mistakes in the past can feel uncomfortable or embarrassing.

So it seems like little wonder, then, that according to research by Gallup , 86% of employees say that they don’t find performance reviews helpful for driving improvement. Getting this part of the performance review right requires introspection, a non-judgmental attitude, and asking yourself the right questions to guide self-evaluation.

To get things started, use our tips in this article to help guide your reflection process. Then, follow up with our Self-Evaluation Template to help you structure your written evaluation.

{{rich-takeaway}}

What is a Self-Assessment Performance Review?

The self-assessment performance review is a key part of the performance management process. It’s a chance for self-reflection on your job performance, including your core strengths and areas for improvement. It also paints a picture for your manager of how you view yourself in relation to your team and the company as a whole, and surfaces any career aspirations or growth needs.

Self-assessment performance appraisals help employees see how their work contributes to the organization and their overall career aspirations, making them far more motivated to do their best work. They’re linked to increased employee performance, higher levels of job satisfaction, and improved employee engagement.

Benefits of employee self-evaluation include:

- Set goals more effectively: A 2020 study on managerial feedback found that focusing on future actions, rather than dwelling on past events, leads to better performance. When we evaluate our overall performance in the context of our professional development and progression, it helps us pinpoint the skill sets we need in the future.

- Eliminate performance review bias: A 2019 study on 30 years of performance management research found that when employees participate in the performance management process, it leads to greater satisfaction in the outcome. Employees were more likely to say the process felt fair and unbiased, because their participation created a two-way, collaborative process.