Protection of Random Assignment

- First Online: 14 October 2021

Cite this chapter

- Lynda H. Powell 4 ,

- Peter G. Kaufmann 5 &

- Kenneth E. Freedland 6

654 Accesses

Existence of an alternative explanation for the benefit of a treatment is a confounder. It is a nuisance “passenger” variable that rides along with treatment and undermines the ability to make causal inferences. This chapter focuses on why random assignment is so powerful and should be protected. It presents a history of attempts to answer the question of whether or not a treatment works, and the arrival at random assignment as the best way to make causal inferences about the benefits of a treatment. It defines confounding as an error of interpretation and the essential role of avoiding it by protecting the random assignment. It then goes on to illustrate ways to protect random assignment in the design, conduct, and analyses of a trial, with particular attention to the central role of identifying a patient-centered target population, recruiting it, retaining it, and insuring that all randomized participants are included in the evaluation of trial results.

“Daniel and his three companions were young Israelites who were taken to serve in the palace of the king of Babylon because they were of noble royal family, without physical defect, handsome, versed in wisdom, and competent. Daniel determined he would not defile himself with the King’s food or wine. He asked the overseer: ‘Please test us for 10 days and let us be given some vegetables to eat and water to drink. Then let our appearance be compared to the appearance of youths who are eating the King’s choice food.’ At the end of 10 days, their appearance seemed better and they were fatter than any of the youths who had been eating the King’s food. So the overseer let them continue to eat vegetables and drink water instead of what the king provided.” Bible, Old Testament, Book of Daniel 1:16

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The Virtues and Limitations of Randomized Experiments

Outcome-adaptive randomization in clinical trials: issues of participant welfare and autonomy

Review of Designs for Accommodating Patients’ or Physicians’ Preferences in Randomized Controlled Trials

Bull JP (1959) The historical development of clinical therapeutic trials. J Chron Dis 10:218–248

PubMed Google Scholar

Armitage P (1982) The role of randomization in clinical trials. Stat Med 1:345–352

Van Helmont JB (1662) Oriatrike or Physik Refined. In Debus AG (1968) The chemical dream of the renaissance. Heffer, London

Google Scholar

Peirce CS, Jastrow J (1884) Fifth memoir: on small differences of sensation. Ntl Acad Sci 3:73–83

Yule G (1924) The function of statistical method in scientific investigation. Industrial Health Research Board Report 28. His Majesty’s Stationery Office, London

Eliot MM (1925) The control of rickets: preliminary discussion of the demonstration in New Haven. JAMA 85:656–663

Hill AB (1952) The clinical trial. New Engl J Med 247:113–119

Hill AB (1953) Observation and experiment. New Engl J Med 248:995–1001

Sinclair HM (1951) Nutritional surveys of population groups. New Engl J Med 245:39–47

Mill JS (1843) A system of logic ratiocinative and inductive. Being a connected view of the principles of evidence and the methods of scientific investigation. Book I. In Robson JM (ed). The collected works of John Stuart Mill (1974). University of Toronto Press, Toronto

Hill AB (1965) The environment and disease: association or causation. Proc Roy Soc Med 58:295–300

Wang D, Bakhai A (2006) Clinical trials: a practical guide to design, analysis, and reporting. Remedica, London

Domanski M, McKinlay S (2009) Successful randomized trials. A handbook for the 21st century. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia

Friedman LM, Furberg CD, DeMets D, Reboussin DH, Granger CB (2015) Fundamentals of clinical trials, 5th edn. Springer, Cham

Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL (2008) Modern epidemiology, 3rd edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia

Szklo M, Nieto FJ (2019) Epidemiology: beyond the basics, 4th edn. Jones & Bartlett Learning, Burlington

Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Mayrent SL (1987) Epidemiology in medicine. Little Brown, Boston

Susser M (1973) Causal thinking in the health sciences: Concepts and strategies of epidemiology. Oxford University Press, New York

Fisher RA (1951) The design of experiments, 6th edn. Hafner, New York

Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT (2002) Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton Mifflin, Boston

Byar DP, Simon RM, Friedewald WT, Schlesselman JJ, DeMets D, Ellenberg JH, Gail MH, Ware JH (1976) Randomized clinical trials--perspectives on some recent ideas. N Engl J Med 295:74–80

Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gotzche PC, Devereaux PJ, Elbourne D, Egger M, Altman DG (2010) CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 340:c869. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c869

Mosteller F, Gilbert JP, McPeek B (1980) Reporting standards and research strategies for controlled trials. Control Clin Trials 1:37–58

Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG (1995) Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 273:408–412

CONSORT Group (2010) CONSORT checklist. www.consort-statement.org

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, CONSORT Group (2010) CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med 152:726–732

Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, Altman DG, Tunis S, Haynes B, Oxman AD, Moher D, and for the CONSORT and Pragmatic Trials in Healthcare (Practihc) groups (2008) Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ 337:a2390. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a2390

Schulz KF (1995) Subverting randomization in controlled trials. JAMA 274:1456–1458

Kraemer HC (2015) A source of false findings in published research studies: adjusting for covariates. JAMA Psychiatry 72:961–962

Pocock SJ, Assmann SE, Enos LE, Kasten LE (2002) Subgroup analysis, covariate adjustment and baseline comparisons in clinical trial reporting: current practice and problems. Stat Med 21:2917–2930

Schulz KF, Grimes DA, Altman DG, Hayes RJ (1996) Blinding and exclusions after allocation in randomised controlled trials: survey of published parallel group trials in obstetrics and gynaecology. BMJ 312:742–744

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Detry MA, Lewis RJ (2014) The intention-to-treat principle: how to assess the true effect of choosing a medical treatment. JAMA 312:85–86

Freedman B (1987) Equipoise and the ethics of clinical research. N Eng J Med 317:141–145

Green SB, Byar DP (1984) Using observational data from registries to compare treatments: the fallacy of omnimetrics. Stat Med 3:361–373

Hollon SD, Wampold BE (2009) Are randomized controlled trials relevant to clinical practice? Can J Psychiatry 54:637–643

Cook TD, Campbell DT (1979) Quasi-experimentation: Design and analysis issues for field settings. Houghton Mifflin, Boston

Glasgow RE, Lichtenstein E, Marcus AC (2003) Why don’t we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? Rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. Am J Public Health 93:1261–1267

Areán PA, Kraemer HC (2013) High-quality psychotherapy research: From conception to piloting to national trials. Oxford University Press, New York

Brownell KD, Wadden TA (1992) Etiology and treatment of obesity: understanding a serious, prevalent, and refractory disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 60:505–517

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC (1992) In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. Am Psychol 47:1102–1114

Hall SM, Tsoh JY, Prochaska JJ, Eisendrath S, Rossi JS, Redding CA, Rosen AB, Meisner M, Humfleet GL, Gorecki JA (2006) Treatment for cigarette smoking among depressed mental health outpatients: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Public Health 96:1808–1814

Prochaska JJ, Hall SE, Delucchi K, Hall SM (2014) Efficacy of initiating tobacco dependence treatment in inpatient psychiatry: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health 104:1557–1565

Prochaska JJ, Hall SE, Hall SM (2009) Stage-tailored tobacco cessation treatment in inpatient psychiatry. Psychiatr Serv 60:848. https://doi:10.1176/appi.ps.60.6.848

Prochaska JJ, Velicer WF, Prochaska JO, Delucchi K, Hall SM (2006) Comparing intervention outcomes in smokers treated for single versus multiple behavioral risks. Health Psychol 25:380–388

The Steering Committee of the Physicians Health Study Research Group (1988) Preliminary report: findings from the aspirin component of the ongoing Physicians’ Health Study. N Engl J Med 318:262–264

Coronary Drug Project Research Group (1980) Influence of adherence to treatment and response of cholesterol on mortality in the Coronary Drug Project. N Engl J Med 303:1038–1041

Adamson J, Cockayne S, Puffer S, Torgerson DJ (2006) Review of randomised trials using the post-randomised consent (Zelen’s) design. Contemp Clin Trials 27:305–319

Fabricatore AN, Wadden TA, Moore RH, Butryn ML, Gravallese EA, Erondu NE, Heymsfield SB, Nguyen AM (2009) Attrition from randomized controlled trials of pharmacological weight loss agents: a systematic review and analysis. Obes Rev 10:333–341

Lang JM (1990) The use of a run-in to enhance compliance. Stat Med 9:87–93

Kong W, Langlois MF, Kamga-Ngandé C, Gagnon C, Brown C, Baillargeon JP (2010) Predictors of success to weight-loss intervention program in individuals at high risk for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 90:147–153

Teixeira PJ, Going SB, Houtkooper LB, Cussler EC, Metcalfe LL, Blew RM, Sardinha LB, Lohman TG (2004) Pretreatment predictors of attrition and successful weight management in women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 28:1124–1133

Czajkowski SM, Powell LH, Adler N, Naar-King S, Reynolds KD, Hunter CM, Laraia B, Olster DH, Perna FM, Peterson JC, Epel E, Boyington JE, Charlson ME (2015) From ideas to efficacy: the ORBIT model for developing behavioral treatments for chronic diseases. Health Psychol 34:971–982

Bailey JV, Pavlou M, Copas A, McCarthy OL, Carswell K, Rait G, Hart G, Nazareth I, Free CJ, French R, Murray E (2013) The Sexunzipped trial: optimizing the design of online randomized controlled trials. J Med Internet Res 15:e278. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2668

Boyd A, Tilling K, Cornish R, Davies A, Humphries K, Macleod J (2015) Professionally designed information materials and telephone reminders improved consent response rates: evidence from an RCT nested within a cohort study. J Clin Epidemiol 68:877–887

Dickson S, Logan J, Hagen S, Stark D, Glazener C, McDonald AM, McPherson G (2013) Reflecting on the methodological challenges of recruiting to a United Kingdom-wide, multi-centre, randomised controlled trial in gynaecology outpatient settings. Trials 14:389. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-14-389

Gupta A, Calfas KJ, Marshall SJ, Robinson TN, Rock CL, Huang JS, Epstein-Corbin M, Servetas C, Donohue MC, Norman GJ, Raab F, Merchant G, Fowler JH, Griswold WG, Fogg BJ, Patrick K (2015) Clinical trial management of participant recruitment, enrollment, engagement, and retention in the SMART study using a Marketing and Information Technology (MARKIT) model. Contemp Clin Trials 42:185–195

Hadidi N, Buckwalter K, Lindquist R, Rangen C (2012) Lessons learned in recruitment and retention of stroke survivors. J Neurosci Nurs 44:105–110

Hartlieb KB, Jacques-Tiura AJ, Naar-King S, Ellis DA, Jen KL, Marshall S (2015) Recruitment strategies and the retention of obese urban racial/ethnic minority adolescents in clinical trials: the FIT families project, Michigan, 2010–2014. Prev Chronic Dis 12:E22. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd12.140409

Johnson DA, Joosten YA, Wilkins CH, Shibao CA (2015) Case study. Community engagement and clinical trial success: outreach to African American women. Clin Transl Sci 8:388–390

Blake K, Holbrook JT, Antal H, Shade D, Bunnell HT, McCahan SM, Wise RA, Pennington C, Garfinkel P, Wysocki T (2015) Use of mobile devices and the internet for multimedia informed consent delivery and data entry in a pediatric asthma trial: study design and rationale. Contemp Clin Trials 42:105–118

Cermak SA, Stein Duker LI, Williams ME, Lane CJ, Dawson ME, Borreson AE, Polido JC (2015) Feasibility of a sensory-adapted dental environment for children with autism. Am J Occup Ther 69:6903220020. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2015.013714

Giuffrida A, Torgerson DJ (1997) Should we pay the patient? Review of financial incentives to enhance patient compliance. BMJ 315:703–707

Brown SD, Lee K, Schoffman DE, King AC, Crawley LM, Kiernan M (2012) Minority recruitment into clinical trials: experimental findings and practical implications. Contemp Clin Trials 33:620–623

Kiernan M, Phillips K, Fair JM, King AC (2000) Using direct mail to recruit Hispanic adults into a dietary intervention: an experimental study. Ann Behav Med 22:89–93

Batliner T, Fehringer KA, Tiwari T, Henderson WG, Wilson A, Brega AG, Albino J (2014) Motivational interviewing with American Indian mothers to prevent early childhood caries: study design and methodology of a randomized control trial. Trials 15:125. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-15-125

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Clark F, Pyatak EA, Carlson M, Blanche E, Vigen C, Hay J, Mallinson T, Blanchard J, Unger JB, Garber SL, Diaz J, Florindez L, Atkins M, Rubayi S, Azen SP, PUPS Study Group (2014) Implementing trials of complex interventions in community settings: the USC-Rancho Los Amigos Pressure Ulcer Prevention Study (PUPS). Clin Trials 11:218–229

Cruz TH, Davis SM, FitzGerald CA, Canaca GF, Keane PC (2014) Engagement, recruitment, and retention in a trans-community, randomized controlled trial for the prevention of obesity in rural American Indian and Hispanic children. J Prim Prev 35:135–149

Jimenez DE, Reynolds CF 3rd, Alegría M, Harvey P, Bartels SJ (2015) The Happy Older Latinos are Active (HOLA) health promotion and prevention study: study protocol for a pilot randomized controlled trial. Trials 6:579. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-015-1113-3

Koziol-McLain J, Vandal AC, Nada-Raja S, Wilson D, Glass NE, Eden KB, McLean C, Dobbs T, Case J (2015) A web-based intervention for abused women: the New Zealand isafe randomised controlled trial protocol. BMC Public Health 15:56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1395-0

Bakari M, Munseri P, Francis J, Aris E, Moshiro C, Siyame D, Janabi M, Ngatoluwa M, Aboud S, Lyamuya E, Sandström E, Mhalu F (2013) Experiences on recruitment and retention of volunteers in the first HIV vaccine trial in Dar es Salam, Tanzania - the phase I/II HIVIS 03 trial. BMC Public Health 13:1149. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1149

Goldberg JH, Kiernan M (2005) Innovative techniques to address retention in a behavioral weight-loss trial. Health Educ Res 20:439–447

National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical Behavioral Research (1978) The Belmont report: ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. ERIC Clearinghouse, Bethesda

Moseley JB, O’Malley K, Petersen NJ, Menke TJ, Brody BA, Kuykendall DH, Hollingsworth JC, Ashton CM, Wray NP (2002) A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med 347:81–88

Hays JL, Hunt JR, Hubbell FA, Anderson GL, Limacher MC, Allen C, Rossouw JE (2003) The Women’s Health Initiative recruitment methods and results. Ann Epidemiol 13:S18–S77

Kaptchuk TJ, Friedlander E, Kelley JM, Sanchez MN, Kokkotou E, Singer JP, Kowalczykowski M, Miller FG, Kirsch I, Lembo AJ (2010) Placebos without deception: a randomized controlled trial in irritable bowel syndrome. PLoS One 5:e15591. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0015591

Crichton GE, Howe PR, Buckley JD, Coates AM, Murphy KJ, Bryan J (2012) Long-term dietary intervention trials: critical issues and challenges. Trials 13:111. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-13-111

Hulley SB, Cummings SR, Browner WS, Grady DG, Newman TB (2013) Designing clinical research, 4th edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia

Siddiqi AE, Sikorskii A, Given CW, Given B (2008) Early participant attrition from clinical trials: role of trial design and logistics. Clin Trials 5:328–335

Idoko OT, Owolabi OA, Odutola AA, Ogundare O, Worwui A, Saidu Y, Smith-Sanneh A, Tunkara A, Sey G, Sanyang A, Mendy P, Ota MO (2014) Lessons in participant retention in the course of a randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Res Notes 7:706. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-7-706

Rucker-Whitaker C, Flynn KJ, Kravitz G, Eaton C, Calvin JE, Powell LH (2006) Understanding African-American participation in a behavioral intervention: results from focus groups. Contemp Clin Trials 27:274–286

Gross D, Fogg L (2004) A critical analysis of the intent-to-treat principle in prevention research. J Primary Prevention 25:475–489

Feinstein AR (1991) Intent-to-treat policy for analyzing randomized trials: statistical distortions and neglected clinical challenges. In: Cramer JA, Spilker B (eds) Patient compliance in medical practice and clinical trials. Raven, New York

Sheiner LB, Rubin DB (1995) Intention-to-treat analysis and the goals of clinical trials. Clin Pharmacol Ther 57:6–15

Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM, Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group (2002) Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 346:393–403

Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group (1999) The Diabetes Prevention Program. Design and methods for a clinical trial in the prevention of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 22:623–634

Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group (2000) The Diabetes Prevention Program: baseline characteristics of the randomized cohort. Diabetes Care 23:1619–1629

Frasure-Smith N, Prince R (1985) The Ischemic Heart Disease Life Stress Monitoring Program. Impact on mortality. Psychosom Med 47:431–445

Frasure-Smith N, Prince R (1989) Long-term follow-up of the Ischemic Heart Disease Life Stress Monitoring Program. Psychosom Med 51:485–513

Powell LH (1989) Unanswered questions in the Ischemic Heart Disease Life Stress Monitoring Program. Psychosom Med 51:479–484

Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F, Prince RH, Verrier P, Garber RA, Juneau M, Wolfson C, Bourassa MG (1997) Randomised trial of home-based psychosocial nursing intervention for patients recovering from myocardial infarction. Lancet 350:473–479

O’Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Lee KL, Keteyian SJ, Cooper LS, Ellis SJ, Leifer ES, Kraus WE, Kitzman DW, Blumenthal JA, Rendall DS, Miller NH, Fleg JL, Schulman KA, McKelvie RS, Zannad F, Piña IL, HF-ACTION Investigators (2009) Efficacy and safety of exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA 301:1439–1450

Keteyian SJ, Leifer ES, Houston-Miller N, Kraus WE, Brawner CA, O’Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Cooper LS, Fleg JL, Kitzman DW, Cohen-Solal A, Blumenthal JA, Rendall DS, Piña IL, HF-ACTION Investigators (2012) Relation between volume of exercise and clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 60:1899–1905

Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL, American College of Cardiology Foundation, American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (2013) 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 62:e147–e239

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2014) Decision memo for cardiac rehabilitation programs - chronic heart failure (CAG-00437N). US Department of Health & Human Services. http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?

McCambridge J, Kypri K, Elbourne D (2014) In randomization we trust? There are overlooked problems in experimenting with people in behavioral intervention trials. J Clin Epidemiol 67:247–253

Ashley EA (2015) The precision medicine initiative: a new national effort. JAMA 313:2019–2020

Khoury MJ, Evans JP (2015) A public health perspective on a national precision medicine cohort: balancing long-term knowledge generation with early health benefit. JAMA 313:2117–2118

Ma J, Rosas LG, Lv N (2016) Precision lifestyle medicine: a new frontier in the science of behavior change and population health. Am J Prev Med 50:395–397

Brewin CR, Bradley C (1989) Patient preferences and randomised clinical trials. Br Med J 299:313–315

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Preventive Medicine, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL, USA

Lynda H. Powell

College of Nursing, Villanova University, Villanova, PA, USA

Peter G. Kaufmann

Department of Psychiatry, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, USA

Kenneth E. Freedland

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Powell, L.H., Kaufmann, P.G., Freedland, K.E. (2021). Protection of Random Assignment. In: Behavioral Clinical Trials for Chronic Diseases. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39330-4_8

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39330-4_8

Published : 14 October 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-39328-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-39330-4

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Random Assignment in Psychology (Intro for Students)

Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

Random assignment is a research procedure used to randomly assign participants to different experimental conditions (or ‘groups’). This introduces the element of chance, ensuring that each participant has an equal likelihood of being placed in any condition group for the study.

It is absolutely essential that the treatment condition and the control condition are the same in all ways except for the variable being manipulated.

Using random assignment to place participants in different conditions helps to achieve this.

It ensures that those conditions are the same in regards to all potential confounding variables and extraneous factors .

Why Researchers Use Random Assignment

Researchers use random assignment to control for confounds in research.

Confounds refer to unwanted and often unaccounted-for variables that might affect the outcome of a study. These confounding variables can skew the results, rendering the experiment unreliable.

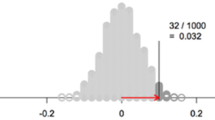

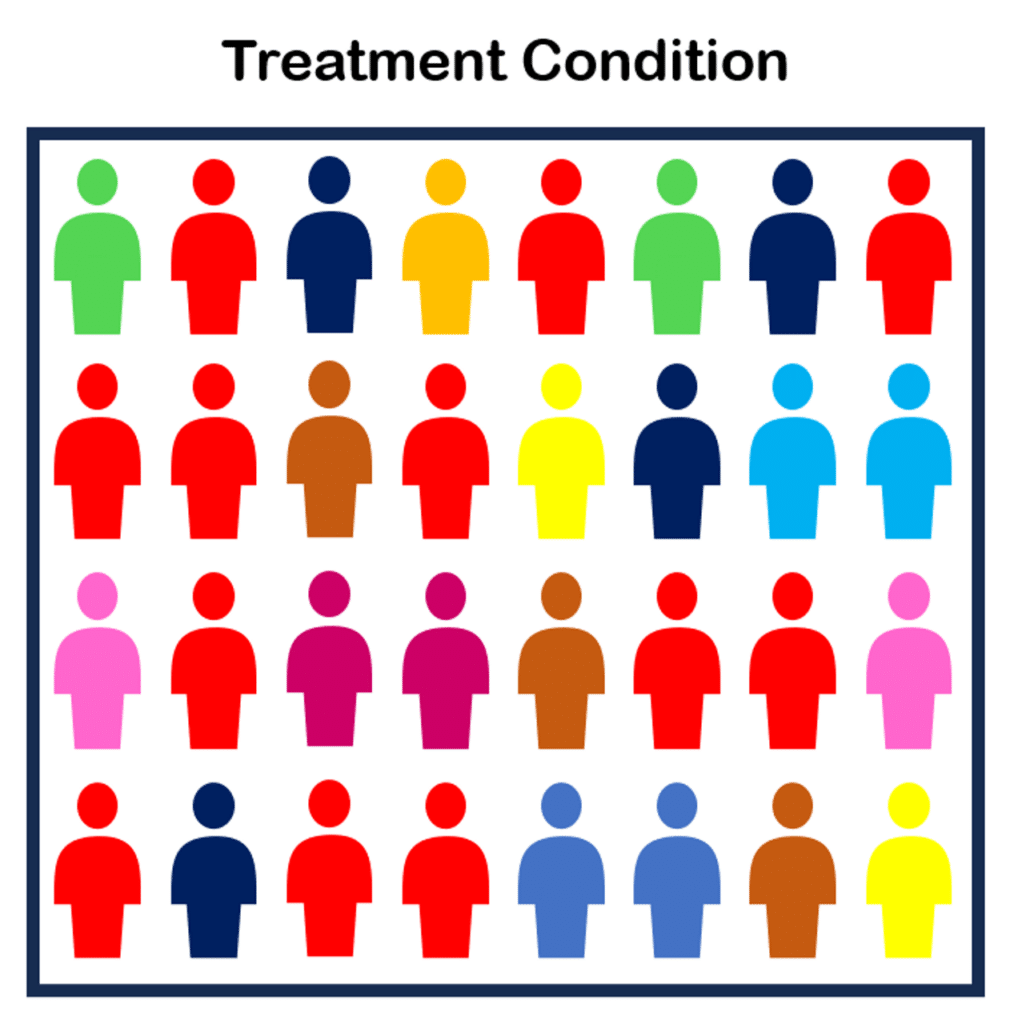

For example, below is a study with two groups. Note how there are more ‘red’ individuals in the first group than the second:

There is likely a confounding variable in this experiment explaining why more red people ended up in the treatment condition and less in the control condition. The red people might have self-selected, for example, leading to a skew of them in one group over the other.

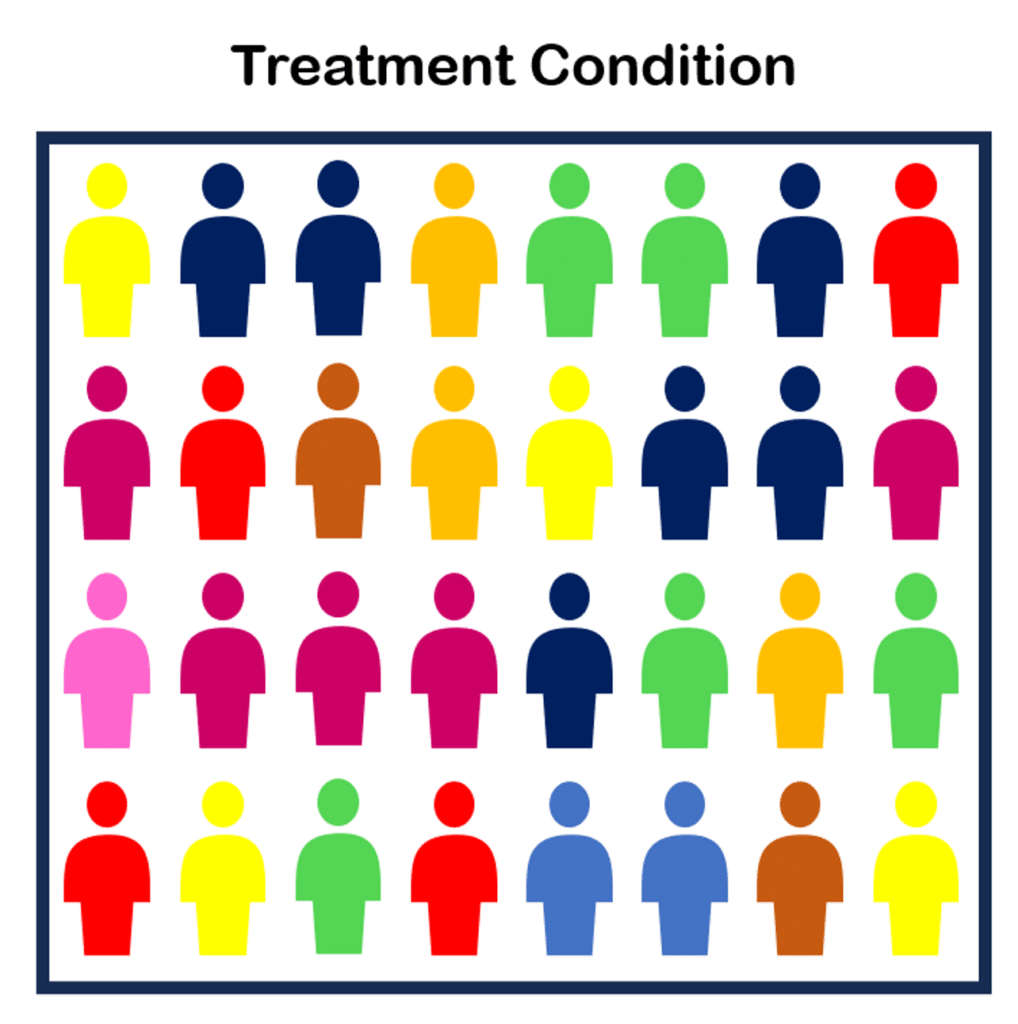

Ideally, we’d want a more even distribution, like below:

To achieve better balance in our two conditions, we use randomized sampling.

Fact File: Experiments 101

Random assignment is used in the type of research called the experiment.

An experiment involves manipulating the level of one variable and examining how it affects another variable. These are the independent and dependent variables :

- Independent Variable: The variable manipulated is called the independent variable (IV)

- Dependent Variable: The variable that it is expected to affect is called the dependent variable (DV).

The most basic form of the experiment involves two conditions: the treatment and the control .

- The Treatment Condition: The treatment condition involves the participants being exposed to the IV.

- The Control Condition: The control condition involves the absence of the IV. Therefore, the IV has two levels: zero and some quantity.

Researchers utilize random assignment to determine which participants go into which conditions.

Methods of Random Assignment

There are several procedures that researchers can use to randomly assign participants to different conditions.

1. Random number generator

There are several websites that offer computer-generated random numbers. Simply indicate how many conditions are in the experiment and then click. If there are 4 conditions, the program will randomly generate a number between 1 and 4 each time it is clicked.

2. Flipping a coin

If there are two conditions in an experiment, then the simplest way to implement random assignment is to flip a coin for each participant. Heads means being assigned to the treatment and tails means being assigned to the control (or vice versa).

3. Rolling a die

Rolling a single die is another way to randomly assign participants. If the experiment has three conditions, then numbers 1 and 2 mean being assigned to the control; numbers 3 and 4 mean treatment condition one; and numbers 5 and 6 mean treatment condition two.

4. Condition names in a hat

In some studies, the researcher will write the name of the treatment condition(s) or control on slips of paper and place them in a hat. If there are 4 conditions and 1 control, then there are 5 slips of paper.

The researcher closes their eyes and selects one slip for each participant. That person is then assigned to one of the conditions in the study and that slip of paper is placed back in the hat. Repeat as necessary.

There are other ways of trying to ensure that the groups of participants are equal in all ways with the exception of the IV. However, random assignment is the most often used because it is so effective at reducing confounds.

Read About More Methods and Examples of Random Assignment Here

Potential Confounding Effects

Random assignment is all about minimizing confounding effects.

Here are six types of confounds that can be controlled for using random assignment:

- Individual Differences: Participants in a study will naturally vary in terms of personality, intelligence, mood, prior knowledge, and many other characteristics. If one group happens to have more people with a particular characteristic, this could affect the results. Random assignment ensures that these individual differences are spread out equally among the experimental groups, making it less likely that they will unduly influence the outcome.

- Temporal or Time-Related Confounds: Events or situations that occur at a particular time can influence the outcome of an experiment. For example, a participant might be tested after a stressful event, while another might be tested after a relaxing weekend. Random assignment ensures that such effects are equally distributed among groups, thus controlling for their potential influence.

- Order Effects: If participants are exposed to multiple treatments or tests, the order in which they experience them can influence their responses. Randomly assigning the order of treatments for different participants helps control for this.

- Location or Environmental Confounds: The environment in which the study is conducted can influence the results. One group might be tested in a noisy room, while another might be in a quiet room. Randomly assigning participants to different locations can control for these effects.

- Instrumentation Confounds: These occur when there are variations in the calibration or functioning of measurement instruments across conditions. If one group’s responses are being measured using a slightly different tool or scale, it can introduce a confound. Random assignment can ensure that any such potential inconsistencies in instrumentation are equally distributed among groups.

- Experimenter Effects: Sometimes, the behavior or expectations of the person administering the experiment can unintentionally influence the participants’ behavior or responses. For instance, if an experimenter believes one treatment is superior, they might unconsciously communicate this belief to participants. Randomly assigning experimenters or using a double-blind procedure (where neither the participant nor the experimenter knows the treatment being given) can help control for this.

Random assignment helps balance out these and other potential confounds across groups, ensuring that any observed differences are more likely due to the manipulated independent variable rather than some extraneous factor.

Limitations of the Random Assignment Procedure

Although random assignment is extremely effective at eliminating the presence of participant-related confounds, there are several scenarios in which it cannot be used.

- Ethics: The most obvious scenario is when it would be unethical. For example, if wanting to investigate the effects of emotional abuse on children, it would be unethical to randomly assign children to either received abuse or not. Even if a researcher were to propose such a study, it would not receive approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) which oversees research by university faculty.

- Practicality: Other scenarios involve matters of practicality. For example, randomly assigning people to specific types of diet over a 10-year period would be interesting, but it would be highly unlikely that participants would be diligent enough to make the study valid. This is why examining these types of subjects has to be carried out through observational studies . The data is correlational, which is informative, but falls short of the scientist’s ultimate goal of identifying causality.

- Small Sample Size: The smaller the sample size being assigned to conditions, the more likely it is that the two groups will be unequal. For example, if you flip a coin many times in a row then you will notice that sometimes there will be a string of heads or tails that come up consecutively. This means that one condition may have a build-up of participants that share the same characteristics. However, if you continue flipping the coin, over the long-term, there will be a balance of heads and tails. Unfortunately, how large a sample size is necessary has been the subject of considerable debate (Bloom, 2006; Shadish et al., 2002).

“It is well known that larger sample sizes reduce the probability that random assignment will result in conditions that are unequal” (Goldberg, 2019, p. 2).

Applications of Random Assignment

The importance of random assignment has been recognized in a wide range of scientific and applied disciplines (Bloom, 2006).

Random assignment began as a tool in agricultural research by Fisher (1925, 1935). After WWII, it became extensively used in medical research to test the effectiveness of new treatments and pharmaceuticals (Marks, 1997).

Today it is widely used in industrial engineering (Box, Hunter, and Hunter, 2005), educational research (Lindquist, 1953; Ong-Dean et al., 2011)), psychology (Myers, 1972), and social policy studies (Boruch, 1998; Orr, 1999).

One of the biggest obstacles to the validity of an experiment is the confound. If the group of participants in the treatment condition are substantially different from the group in the control condition, then it is impossible to determine if the IV has an affect or if the confound has an effect.

Thankfully, random assignment is highly effective at eliminating confounds that are known and unknown. Because each participant has an equal chance of being placed in each condition, they are equally distributed.

There are several ways of implementing random assignment, including flipping a coin or using a random number generator.

Random assignment has become an essential procedure in research in a wide range of subjects such as psychology, education, and social policy.

Alferes, V. R. (2012). Methods of randomization in experimental design . Sage Publications.

Bloom, H. S. (2008). The core analytics of randomized experiments for social research. The SAGE Handbook of Social Research Methods , 115-133.

Boruch, R. F. (1998). Randomized controlled experiments for evaluation and planning. Handbook of applied social research methods , 161-191.

Box, G. E., Hunter, W. G., & Hunter, J. S. (2005). Design of experiments: Statistics for Experimenters: Design, Innovation and Discovery.

Dehue, T. (1997). Deception, efficiency, and random groups: Psychology and the gradual origination of the random group design. Isis , 88 (4), 653-673.

Fisher, R.A. (1925). Statistical methods for research workers (11th ed. rev.). Oliver and Boyd: Edinburgh.

Fisher, R. A. (1935). The Design of Experiments. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd.

Goldberg, M. H. (2019). How often does random assignment fail? Estimates and recommendations. Journal of Environmental Psychology , 66 , 101351.

Jamison, J. C. (2019). The entry of randomized assignment into the social sciences. Journal of Causal Inference , 7 (1), 20170025.

Lindquist, E. F. (1953). Design and analysis of experiments in psychology and education . Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Marks, H. M. (1997). The progress of experiment: Science and therapeutic reform in the United States, 1900-1990 . Cambridge University Press.

Myers, J. L. (1972). Fundamentals of experimental design (2nd ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

Ong-Dean, C., Huie Hofstetter, C., & Strick, B. R. (2011). Challenges and dilemmas in implementing random assignment in educational research. American Journal of Evaluation , 32 (1), 29-49.

Orr, L. L. (1999). Social experiments: Evaluating public programs with experimental methods . Sage.

Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Quasi-experiments: interrupted time-series designs. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference , 171-205.

Stigler, S. M. (1992). A historical view of statistical concepts in psychology and educational research. American Journal of Education , 101 (1), 60-70.

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 18 Adaptive Behavior Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Ableism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

IMAGES

VIDEO