Learning Materials

- Business Studies

- Combined Science

- Computer Science

- Engineering

- English Literature

- Environmental Science

- Human Geography

- Macroeconomics

- Microeconomics

- Lab Experiment

What do you think of when you hear the word "laboratory"? Do you picture people in white coats and goggles and gloves standing over a table with beakers and tubes? Well, that picture is pretty close to reality in some cases. In others, laboratory experiments, especially in psychology, focus more on observing behaviours in highly controlled settings to establish causal conclusions. Let's explore lab experiments further.

Millions of flashcards designed to help you ace your studies

- Cell Biology

The aim of lab experiments is to identify if observed changes in the are caused by the .

Is it difficult to generalise results from lab experiments to real-life settings?

Demand characteristics lower the of the research.

True or false: there is more likelihood of demand characteristics influencing lab experiments than field experiments.

A researcher wanted to explore how driving conditions affected speeding. Which type of experimental method is the researcher more likely to use?

A researcher wanted to explore if sleep deprivation affected cognitive abilities. Which type of experimental method is the researcher more likely to use?

Are lab experiments easy to replicate?

True or false: Participants are aware that they are taking part in the lab experiment and sometimes may not know the aim of the investigation.

Review generated flashcards

to start learning or create your own AI flashcards

Start learning or create your own AI flashcards

- Approaches in Psychology

- Basic Psychology

- Biological Bases of Behavior

- Biopsychology

- Careers in Psychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognition and Development

- Cognitive Psychology

- Data Handling and Analysis

- Developmental Psychology

- Eating Behaviour

- Emotion and Motivation

- Famous Psychologists

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- Individual Differences Psychology

- Issues and Debates in Psychology

- Personality in Psychology

- Psychological Treatment

- Relationships

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Aims and Hypotheses

- Causation in Psychology

- Coding Frame Psychology

- Correlational Studies

- Cross Cultural Research

- Cross Sectional Research

- Ethical Issues and Ways of Dealing with Them

- Experimental Designs

- Features of Science

- Field Experiment

- Independent Group Design

- Longitudinal Research

- Matched Pairs Design

- Meta Analysis

- Natural Experiment

- Observational Design

- Online Research

- Paradigms and Falsifiability

- Peer Review and Economic Applications of Research

- Pilot Studies and the Aims of Piloting

- Quality Criteria

- Questionnaire Construction

- Repeated Measures Design

- Research Methods

- Sampling Frames

- Sampling Psychology

- Scientific Processes

- Scientific Report

- Scientific Research

- Self-Report Design

- Self-Report Techniques

- Semantic Differential Rating Scale

- Snowball Sampling

- Schizophrenia

- Scientific Foundations of Psychology

- Scientific Investigation

- Sensation and Perception

- Social Context of Behaviour

- Social Psychology

- We are going to delve into the topic of lab experiments in the context of psychology.

- We will start by looking at the lab experiment definition and how lab experiments are used in psychology.

- Moving on from this, we will look at how lab experiment examples in psychology and cognitive lab experiments may be conducted.

- And to finish off, we will also explore the strengths and weaknesses of lab experiments.

Lab Experiment Psychology Definition

You can probably guess from the name that lab experiments occur in lab settings. Although this is not always the case, they can sometimes occur in other controlled environments. The purpose of lab experiments is to identify the cause and effect of a phenomenon through experimentation.

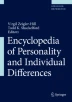

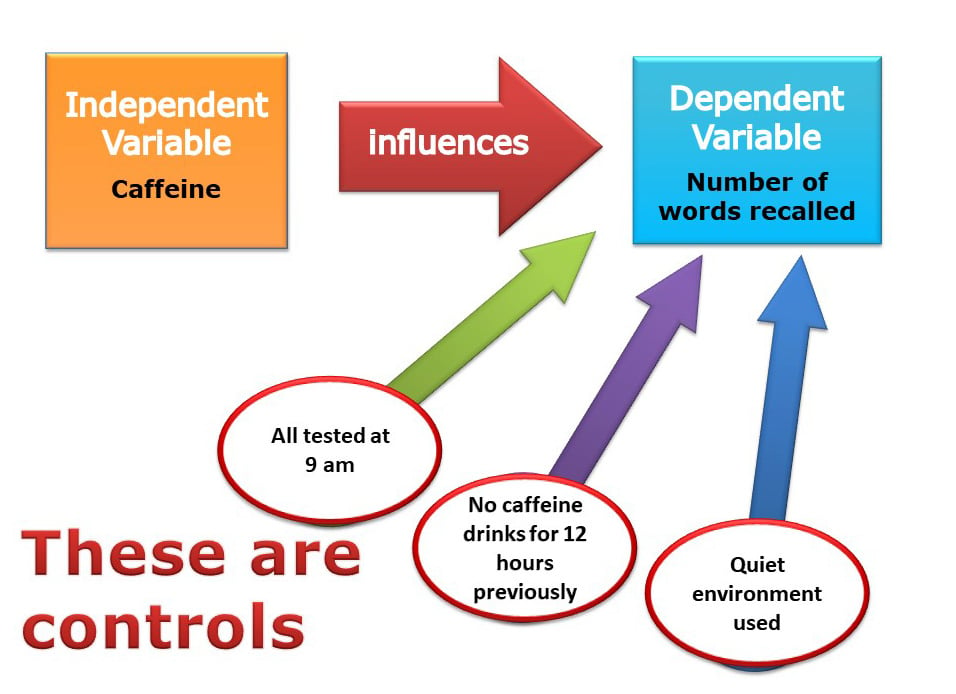

A lab experiment is an experiment that uses a carefully controlled setting and standardised procedure to accurately measure how changes in the independent variable (IV; variable that changes) affects the dependent variable (DV; variable measured).

In lab experiments, the IV is what the researcher predicts as the cause of a phenomenon, and the dependent variable is what the researcher predicts as the effect of a phenomenon.

Lab Experiment: P sychology

Lab experiments in psychology are used when trying to establish causal relationships between variables . For example, a researcher would use a lab experiment if they were investigating how sleep affects memory recall.

The majority of psychologists think of psychology as a form of science. Therefore, they argue that the protocol used in psychological research should resemble those used in the natural sciences. For research to be established as scientific , three essential features should be considered:

- Empiricism - the findings should be observable via the five senses.

- Reliability - if the study was replicated, similar results should be found.

- Validity - the investigation should accurately measure what it intends to.

But do lab experiments fulfil these requirements of natural sciences research? If done correctly, then yes. Lab experiments are empirical as they involve the researcher observing changes occurring in the DV. Reliability is established by using a standardised procedure in lab experiments .

A standardised procedure is a protocol that states how the experiment will be carried out. This allows the researcher to ensure the same protocol is used for each participant, increasing the study's internal reliability.

Standardised procedures are also used to help other researchers replicate the study to identify if they measure similar results.

Dissimilar results reflect low reliability.

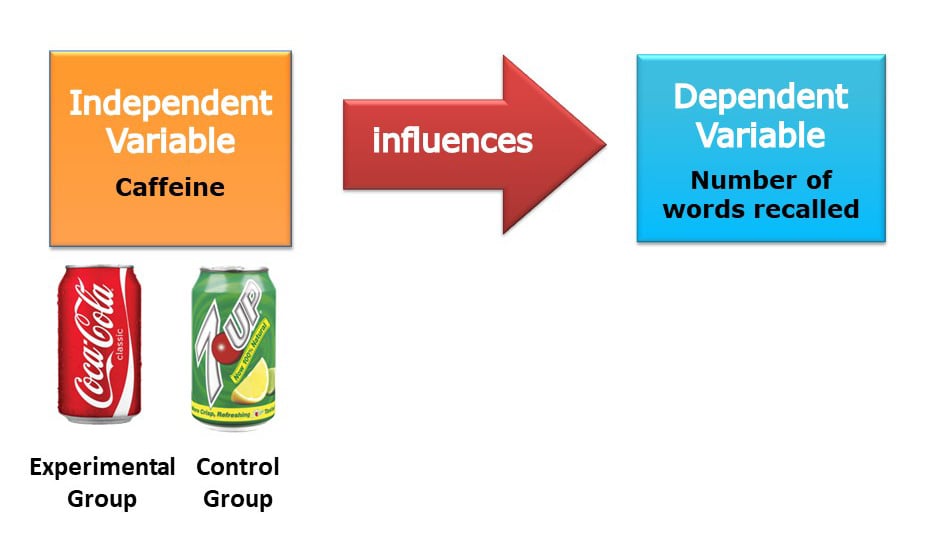

Validity is another feature of a lab experiment considered. Lab experiments are conducted in a carefully controlled setting where the researcher has the most control compared to other experiments to prevent extraneous variables from affecting the DV .

Extraneous variables are factors other than the IV that affect the DV; as these are variables that the researcher is not interested in investigating, these reduce the validity of the research.

There are issues of validity in lab experiments, which we'll get into a bit later!

Lab Experiment Examples: Asch's Conformity Study

The Asch (1951) conformity study is an example of a lab experiment. The investigation aimed to identify if the presence and influence of others would pressure participants to change their response to a straightforward question. Participants were given two pieces of paper, one depicting a 'target line' and another three, one of which resembled the 'target line' and the others of different lengths.

The participants were put in groups of eight. Unknown to the participants, the other seven were confederates (participants who were secretly part of the research team) who were instructed to give the wrong answer. If the actual participant changed their answer in response, this would be an example of conformity .

Asch controlled the location where the investigation took place, constructed a contrived scenario and even controlled the confederates who would affect the behaviour of the actual participants to measure the DV.

Some other famous examples of research that are lab experiment examples include research conducted by Milgram (the obedience study) and Loftus and Palmer's eyewitness testimony accuracy study . These researchers likely used this method because of some of their strengths , e.g., their high level of control .

Lab Experiment Examples: Cognitive Lab Experiments

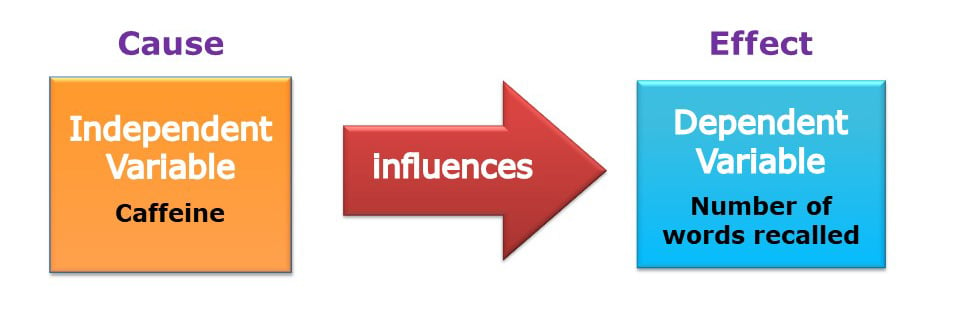

Let's look at what a cognitive lab experiment may entail. Suppose a researcher is interested in investigating how sleep affects memory scores using the MMSE test. In the theoretical study , an equal number of participants were randomly allocated into two groups; sleep-deprived versus well-rested. Both groups completed the memory test after a whole night of sleep or staying awake all night.

In this research scenario , the DV can be identified as memory test scores and the IV as whether participants were sleep-deprived or well-rested.

Some examples of extraneous variables the study controlled include researchers ensuring participants did not fall asleep, the participants took the test at the same time, and participants in the well-rested group slept for the same time.

Lab Experiment Advantages and Disadvantages

It's important to consider the advantages and disadvantages of laboratory experiments . Advantages include the highly controlled setting of lab experiments, the standardised procedures and causal conclusions that can be drawn. Disadvantages include the low ecological validity of lab experiments and demand characteristics participants may present.

Strengths of Lab Experiments: Highly Controlled

Laboratory experiments are conducted in a well-controlled setting. All the variables, including extraneous and confounding variables , are rigidly controlled in the investigation. Therefore, the risk of experimental findings being affected by extraneous or confounding variables is reduced . As a result, the well-controlled design of laboratory experiments implies the research has high internal validity .

Internal validity means the study uses measures and protocols that measure exactly what it intends to, i.e. how only the changes in the IV affect the DV.

Strengths of Lab Experiments: Standardised Procedures

Laboratory experiments have standardised procedures, which means the experiments are replicable , and all participants are tested under the same conditions. T herefore, standardised procedures allow others to replicate the study to identify whether the research is reliable and that the findings are not a one-off result. As a result, the replicability of laboratory experiments allows researchers to verify the study's reliability .

Strengths of Lab Experiments: Causal Conclusions

A well-designed laboratory experiment can draw causal conclusions. Ideally, a laboratory experiment can rigidly control all the variables , including extraneous and confounding variables. Therefore, laboratory experiments provide great confidence to researchers that the IV causes any observed changes in DV.

Weaknesses of Lab Experiments

In the following, we will present the disadvantages of laboratory experiments. This discusses ecological validity and demand characteristics.

Weaknesses of Lab Experiments: Low Ecological Validity

Laboratory experiments have low ecological validity because they are conducted in an artificial study that does not reflect a real-life setting . As a result, findings generated in laboratory experiments can be difficult to generalise to real life due to the low mundane realism. Mundane realism reflects the extent to which lab experiment materials are similar to real-life events.

Weaknesses of Lab Experiments: Demand Characteristics

A disadvantage of laboratory experiments is that the research setting may lead to demand characteristics .

Demand characteristics are the cues that make participants aware of what the experimenter expects to find or how participants are expected to behave.

The participants are aware they are involved in an experiment. So, participants may have some ideas of what is expected of them in the investigation, which may influence their behaviours. As a result, the demand characteristics presented in laboratory experiments can arguably change the research outcome , reducing the findings' validity .

Lab Experiment - Key takeaways

The lab experiment definition is an experiment that uses a carefully controlled setting and standardised procedure to establish how changes in the independent variable (IV; variable that changes) affect the dependent variable (DV; variable measured).

Psychologists aim to ensure that lab experiments are scientific and must be empirical, reliable and valid.

The Asch (1951) conformity study is an example of a lab experiment. The investigation aimed to identify if the presence and influence of others would pressure participants to change their response to a straightforward question.

The advantages of lab experiments are high internal validity, standardised procedures and the ability to draw causal conclusions.

The disadvantages of lab experiments are low ecological validity and demand characteristics.

Flashcards in Lab Experiment 8

Lab experiment.

Learn with 8 Lab Experiment flashcards in the free StudySmarter app

We have 14,000 flashcards about Dynamic Landscapes.

Already have an account? Log in

Frequently Asked Questions about Lab Experiment

What is a lab experiment?

A lab experiment is an experiment that uses a carefully controlled setting and standardised procedure to establish how changes in the independent variable (IV; variable that changes) affects the dependent variable (DV; variable measured).

What is the purpose of lab experiments?

Lab experiments investigate cause-and-effect. They aim to determine the effect of changes in the independent variable on the dependent variable.

What is a lab experiment and field experiment?

A field experiment is an experiment conducted in a natural, everyday setting. The experimenter still controls the IV; however, extraneous and confounding variables may be difficult to control due to the natural setting.

Similar, to filed experiments researchers, can control the IV and extraneous variables. However, this takes place in an artificial setting such as a lab.

Why would a psychologist use a laboratory experiment?

A psychologist may use a lab experiment when trying to establish the causal relationships between variables to explain a phenomenon.

Why is lab experience important?

Lab experience allows researchers to scientifically determine whether a hypothesis/ theory should be accepted or rejected.

What is a lab experiment example?

The research conducted by Loftus and Palmer (accuracy of eyewitness testimony) and Milgram (obedience) used a lab experiment design. These experimental designs give the researcher high control, allowing them to control extraneous and independent variables.

Test your knowledge with multiple choice flashcards

The aim of lab experiments is to identify if observed changes in the are caused by the .

Demand characteristics lower the of the research.

Join the StudySmarter App and learn efficiently with millions of flashcards and more!

Keep learning, you are doing great.

Discover learning materials with the free StudySmarter app

About StudySmarter

StudySmarter is a globally recognized educational technology company, offering a holistic learning platform designed for students of all ages and educational levels. Our platform provides learning support for a wide range of subjects, including STEM, Social Sciences, and Languages and also helps students to successfully master various tests and exams worldwide, such as GCSE, A Level, SAT, ACT, Abitur, and more. We offer an extensive library of learning materials, including interactive flashcards, comprehensive textbook solutions, and detailed explanations. The cutting-edge technology and tools we provide help students create their own learning materials. StudySmarter’s content is not only expert-verified but also regularly updated to ensure accuracy and relevance.

StudySmarter Editorial Team

Team Psychology Teachers

- 8 minutes reading time

- Checked by StudySmarter Editorial Team

Study anywhere. Anytime.Across all devices.

Create a free account to save this explanation..

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

By signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

Join over 22 million students in learning with our StudySmarter App

The first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

- Flashcards & Quizzes

- AI Study Assistant

- Study Planner

- Smart Note-Taking

17 Advantages and Disadvantages of Experimental Research Method in Psychology

There are numerous research methods used to determine if theories, ideas, or even products have validity in a market or community. One of the most common options utilized today is experimental research. Its popularity is due to the fact that it becomes possible to take complete control over a single variable while conducting the research efforts. This process makes it possible to manipulate the other variables involved to determine the validity of an idea or the value of what is being proposed.

Outcomes through experimental research come through a process of administration and monitoring. This structure makes it possible for researchers to determine the genuine impact of what is under observation. It is a process which creates outcomes with a high degree of accuracy in almost any field.

The conclusion can then offer a final value potential to consider, making it possible to know if a continued pursuit of the information is profitable in some way.

The pros and cons of experimental research show that this process is highly efficient, creating data points for evaluation with speed and regularity. It is also an option that can be manipulated easily when researchers want their work to draw specific conclusions.

List of the Pros of Experimental Research

1. Experimental research offers the highest levels of control. The procedures involved with experimental research make it possible to isolate specific variables within virtually any topic. This advantage makes it possible to determine if outcomes are viable. Variables are controllable on their own or in combination with others to determine what can happen when each scenario is brought to a conclusion. It is a benefit which applies to ideas, theories, and products, offering a significant advantage when accurate results or metrics are necessary for progress.

2. Experimental research is useful in every industry and subject. Since experimental research offers higher levels of control than other methods which are available, it offers results which provide higher levels of relevance and specificity. The outcomes that are possible come with superior consistency as well. It is useful in a variety of situations which can help everyone involved to see the value of their work before they must implement a series of events.

3. Experimental research replicates natural settings with significant speed benefits. This form of research makes it possible to replicate specific environmental settings within the controls of a laboratory setting. This structure makes it possible for the experiments to replicate variables that would require a significant time investment otherwise. It is a process which gives the researchers involved an opportunity to seize significant control over the extraneous variables which may occur, creating limits on the unpredictability of elements that are unknown or unexpected when driving toward results.

4. Experimental research offers results which can occur repetitively. The reason that experimental research is such an effective tool is that it produces a specific set of results from documented steps that anyone can follow. Researchers can duplicate the variables used during the work, then control the variables in the same way to create an exact outcome that duplicates the first one. This process makes it possible to validate scientific discoveries, understand the effectiveness of a program, or provide evidence that products address consumer pain points in beneficial ways.

5. Experimental research offers conclusions which are specific. Thanks to the high levels of control which are available through experimental research, the results which occur through this process are usually relevant and specific. Researchers an determine failure, success, or some other specific outcome because of the data points which become available from their work. That is why it is easier to take an idea of any type to the next level with the information that becomes available through this process. There is always a need to bring an outcome to its natural conclusion during variable manipulation to collect the desired data.

6. Experimental research works with other methods too. You can use experimental research with other methods to ensure that the data received from this process is as accurate as possible. The results that researchers obtain must be able to stand on their own for verification to have findings which are valid. This combination of factors makes it possible to become ultra-specific with the information being received through these studies while offering new ideas to other research formats simultaneously.

7. Experimental research allows for the determination of cause-and-effect. Because researchers can manipulate variables when performing experimental research, it becomes possible to look for the different cause-and-effect relationships which may exist when pursuing a new thought. This process allows the parties involved to dig deeply into the possibilities which are present, demonstrating whatever specific benefits are possible when outcomes are reached. It is a structure which seeks to understand the specific details of each situation as a way to create results.

List of the Cons of Experimental Research

1. Experimental research suffers from the potential of human errors. Experimental research requires those involved to maintain specific levels of variable control to create meaningful results. This process comes with a high risk of experiencing an error at some stage of the process when compared to other options that may be available. When this issue goes unnoticed as the results become transferable, the data it creates will reflect a misunderstanding of the issue under observation. It is a disadvantage which could eliminate the value of any information that develops from this process.

2. Experimental research is a time-consuming process to endure. Experimental research must isolate each possible variable when a subject matter is being studied. Then it must conduct testing on each element under consideration until a resolution becomes possible, which then requires data collection to occur. This process must continue to repeat itself for any findings to be valid from the effort. Then combinations of variables must go through evaluation in the same manner. It is a field of research that sometimes costs more than the potential benefits or profits that are achievable when a favorable outcome is eventually reached.

3. Experimental research creates unrealistic situations that still receive validity. The controls which are necessary when performing experimental research increase the risks of the data becoming inaccurate or corrupted over time. It will still seem authentic to the researchers involved because they may not see that a variable is an unrealistic situation. The variables can skew in a specific direction if the information shifts in a certain direction through the efforts of the researchers involved. The research environment can also be extremely different than real-life circumstances, which can invalidate the value of the findings.

4. Experimental research struggles to measure human responses. People experience stress in uncountable ways during the average day. Personal drama, political arguments, and workplace deadlines can influence the data that researchers collect when measuring human response tendencies. What happens inside of a controlled situation is not always what happens in real-life scenarios. That is why this method is not the correct choice to use in group or individual settings where a human response requires measurement.

5. Experimental research does not always create an objective view. Objective research is necessary for it to provide effective results. When researchers have permission to manipulate variables in whatever way they choose, then the process increases the risk of a personal bias, unconscious or otherwise, influencing the results which are eventually obtained. People can shift their focus because they become uncomfortable, are aroused by the event, or want to manipulate the results for their personal agenda. Data samples are therefore only a reflection of that one group instead of offering data across an entire demographic.

6. Experimental research can experience influences from real-time events. The issue with human error in experimental research often involves the researchers conducting the work, but it can also impact the people being studied as well. Numerous outside variables can impact responses or outcomes without the knowledge of researchers. External triggers, such as the environment, political stress, or physical attraction can alter a person’s regular perspective without it being apparent. Internal triggers, such as claustrophobia or social interactions, can alter responses as well. It is challenging to know if the data collected through this process offers an element of honesty.

7. Experimental research cannot always control all of the variables. Although experimental research attempts to control every variable or combination that is possible, laboratory settings cannot reach this limitation in every circumstance. If data must be collected in a natural setting, then the risk of inaccurate information rises. Some research efforts place an emphasis on one set of variables over another because of a perceived level of importance. That is why it becomes virtually impossible in some situations to apply obtained results to the overall population. Groups are not always comparable, even if this process provides for more significant transferability than other methods of research.

8. Experimental research does not always seek to find explanations. The goal of experimental research is to answer questions that people may have when evaluating specific data points. There is no concern given to the reason why specific outcomes are achievable through this system. When you are working in a world of black-and-white where something works or it does not, there are many shades of gray in-between these two colors where additional information is waiting to be discovered. This method ignores that information, settling for whatever answers are found along the extremes instead.

9. Experimental research does not make exceptions for ethical or moral violations. One of the most significant disadvantages of experimental research is that it does not take the ethical or moral violations that some variables may create out of the situation. Some variables cannot be manipulated in ways that are safe for people, the environment, or even the society as a whole. When researchers encounter this situation, they must either transfer their data points to another method, continue on to produce incomplete results, fabricate results, or set their personal convictions aside to work on the variable anyway.

10. Experimental research may offer results which apply to only one situation. Although one of the advantages of experimental research is that it allows for duplication by others to obtain the same results, this is not always the case in every situation. There are results that this method can find which may only apply to that specific situation. If this process is used to determine highly detailed data points which require unique circumstances to obtain, then future researchers may find that result replication is challenging to obtain.

These experimental research pros and cons offer a useful system that can help determine the validity of an idea in any industry. The only way to achieve this advantage is to place tight controls over the process, and then reduce any potential for bias within the system to appear. This makes it possible to determine if a new idea of any type offers current or future value.

Experimental Methods In Psychology

March 7, 2021 - paper 2 psychology in context | research methods.

There are three experimental methods in the field of psychology; Laboratory, Field and Natural Experiments. Each of the experimental methods holds different characteristics in relation to; the manipulation of the IV, the control of the EVs and the ability to accurately replicate the study in exactly the same way.

| | · A highly controlled setting · Artificial setting· High control over the IV and EVs· For example, Loftus and Palmer’s study looking at leading questions | (+) High level of control, researchers are able to control the IV and potential EVs. This is a strength because researchers are able to establish a cause and effect relationship and there is high internal validity. (+) Due to the high level of control it means that a lab experiment can be replicated in exactly the same way under exactly the same conditions. This is a strength as it means that the reliability of the research can be assessed (i.e. a reliable study will produce the same findings over and over again). | (-) Low ecological validity. A lab experiment takes place in an unnatural, artificial setting. As a result participants may behave in an unnatural manner. This is a weakness because it means that the experiment may not be measuring real-life behaviour. (-) Another weakness is that there is a high chance of demand characteristics. For example as the laboratory setting makes participants aware they are taking part in research, this may cause them to change their behaviour in some way. For example, a participant in a memory experiment might deliberately remember less in one experimental condition if they think that is what the experimenter expects them to do to avoid ruining the results. This is a problem because it means that the results do not reflect real-life as they are responding to demand characteristics and not just the independent variable. |

| · Real life setting · Experimenter can control the IV· Experimenter doesn’t have control over EVs (e.g. weather etc )· For example, research looking at altruistic behaviour had a stooge (actor) stage a collapse in a subway and recorded how many passers-by stopped to help. | (+) High ecological validity. Due to the fact that a field experiment takes place in a real-life setting, participants are unaware that they are being watched and therefore are more likely to act naturally. This is a strength because it means that the participants behaviour will be reflective of their real-life behaviour. (+) Another strength is that there is less chance of demand characteristics. For example, because the research consists of a real life task in a natural environment it’s unlikely that participants will change their behaviour in response to demand characteristics. This is positive because it means that the results reflect real-life as they are not responding to demand characteristics, just the independent variable. | (-) Low degree of control over variables. For example, such as the weather (if a study is taking place outdoors), noise levels or temperature are more difficult to control if the study is taking place outside the laboratory. This is problematic because there is a greater chance of extraneous variables affecting participant’s behaviour which reduces the experiments internal validity and makes a cause and effect relationship difficult to establish. (-) Difficult to replicate. For example, if a study is taking place outdoors, the weather might change between studies and affect the participants’ behaviour. This is a problem because it reduces the chances of the same results being found time and time again and therefore can reduce the reliability of the experiment. | |

| · Real-life setting · Experimenter has no control over EVs or the IV· IV is naturally occurring· For example, looking at the changes in levels of aggression after the introduction of the television. The introduction of the TV is the natural occurring IV and the DV is the changes in aggression (comparing aggression levels before and after the introduction of the TV). | The of the natural experiment are exactly the same as the strengths of the field experiment: (+) High ecological validity due to the fact that the research is taking place in a natural setting and therefore is reflective of real-life natural behaviour. (+) Low chance of demand characteristics. Because participants do not know that they are taking part in a study they will not change their behaviour and act unnaturally therefore the experiment can be said to be measuring real-life natural behaviour. | The of the natural experiment are exactly the same as the strengths of the field experiment: (-)Low control over variables. For example, the researcher isn’t able to control EVs and the IV is naturally occurring. This means that a cause and effect relationship cannot be established and there is low internal validity. (-) Due to the fact that there is no control over variables, a natural experiment cannot be replicated and therefore reliability is difficult to assess for. |

When conducting research, it is important to create an aim and a hypothesis, click here to learn more about the formation of aims and hypotheses.

We're not around right now. But you can send us an email and we'll get back to you, asap.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Experimental Research

23 Experiment Basics

Learning objectives.

- Explain what an experiment is and recognize examples of studies that are experiments and studies that are not experiments.

- Distinguish between the manipulation of the independent variable and control of extraneous variables and explain the importance of each.

- Recognize examples of confounding variables and explain how they affect the internal validity of a study.

- Define what a control condition is, explain its purpose in research on treatment effectiveness, and describe some alternative types of control conditions.

What Is an Experiment?

As we saw earlier in the book, an experiment is a type of study designed specifically to answer the question of whether there is a causal relationship between two variables. In other words, whether changes in one variable (referred to as an independent variable ) cause a change in another variable (referred to as a dependent variable ). Experiments have two fundamental features. The first is that the researchers manipulate, or systematically vary, the level of the independent variable. The different levels of the independent variable are called conditions . For example, in Darley and Latané’s experiment, the independent variable was the number of witnesses that participants believed to be present. The researchers manipulated this independent variable by telling participants that there were either one, two, or five other students involved in the discussion, thereby creating three conditions. For a new researcher, it is easy to confuse these terms by believing there are three independent variables in this situation: one, two, or five students involved in the discussion, but there is actually only one independent variable (number of witnesses) with three different levels or conditions (one, two or five students). The second fundamental feature of an experiment is that the researcher exerts control over, or minimizes the variability in, variables other than the independent and dependent variable. These other variables are called extraneous variables . Darley and Latané tested all their participants in the same room, exposed them to the same emergency situation, and so on. They also randomly assigned their participants to conditions so that the three groups would be similar to each other to begin with. Notice that although the words manipulation and control have similar meanings in everyday language, researchers make a clear distinction between them. They manipulate the independent variable by systematically changing its levels and control other variables by holding them constant.

Manipulation of the Independent Variable

Again, to manipulate an independent variable means to change its level systematically so that different groups of participants are exposed to different levels of that variable, or the same group of participants is exposed to different levels at different times. For example, to see whether expressive writing affects people’s health, a researcher might instruct some participants to write about traumatic experiences and others to write about neutral experiences. The different levels of the independent variable are referred to as conditions , and researchers often give the conditions short descriptive names to make it easy to talk and write about them. In this case, the conditions might be called the “traumatic condition” and the “neutral condition.”

Notice that the manipulation of an independent variable must involve the active intervention of the researcher. Comparing groups of people who differ on the independent variable before the study begins is not the same as manipulating that variable. For example, a researcher who compares the health of people who already keep a journal with the health of people who do not keep a journal has not manipulated this variable and therefore has not conducted an experiment. This distinction is important because groups that already differ in one way at the beginning of a study are likely to differ in other ways too. For example, people who choose to keep journals might also be more conscientious, more introverted, or less stressed than people who do not. Therefore, any observed difference between the two groups in terms of their health might have been caused by whether or not they keep a journal, or it might have been caused by any of the other differences between people who do and do not keep journals. Thus the active manipulation of the independent variable is crucial for eliminating potential alternative explanations for the results.

Of course, there are many situations in which the independent variable cannot be manipulated for practical or ethical reasons and therefore an experiment is not possible. For example, whether or not people have a significant early illness experience cannot be manipulated, making it impossible to conduct an experiment on the effect of early illness experiences on the development of hypochondriasis. This caveat does not mean it is impossible to study the relationship between early illness experiences and hypochondriasis—only that it must be done using nonexperimental approaches. We will discuss this type of methodology in detail later in the book.

Independent variables can be manipulated to create two conditions and experiments involving a single independent variable with two conditions are often referred to as a single factor two-level design . However, sometimes greater insights can be gained by adding more conditions to an experiment. When an experiment has one independent variable that is manipulated to produce more than two conditions it is referred to as a single factor multi level design . So rather than comparing a condition in which there was one witness to a condition in which there were five witnesses (which would represent a single-factor two-level design), Darley and Latané’s experiment used a single factor multi-level design, by manipulating the independent variable to produce three conditions (a one witness, a two witnesses, and a five witnesses condition).

Control of Extraneous Variables

As we have seen previously in the chapter, an extraneous variable is anything that varies in the context of a study other than the independent and dependent variables. In an experiment on the effect of expressive writing on health, for example, extraneous variables would include participant variables (individual differences) such as their writing ability, their diet, and their gender. They would also include situational or task variables such as the time of day when participants write, whether they write by hand or on a computer, and the weather. Extraneous variables pose a problem because many of them are likely to have some effect on the dependent variable. For example, participants’ health will be affected by many things other than whether or not they engage in expressive writing. This influencing factor can make it difficult to separate the effect of the independent variable from the effects of the extraneous variables, which is why it is important to control extraneous variables by holding them constant.

Extraneous Variables as “Noise”

Extraneous variables make it difficult to detect the effect of the independent variable in two ways. One is by adding variability or “noise” to the data. Imagine a simple experiment on the effect of mood (happy vs. sad) on the number of happy childhood events people are able to recall. Participants are put into a negative or positive mood (by showing them a happy or sad video clip) and then asked to recall as many happy childhood events as they can. The two leftmost columns of Table 5.1 show what the data might look like if there were no extraneous variables and the number of happy childhood events participants recalled was affected only by their moods. Every participant in the happy mood condition recalled exactly four happy childhood events, and every participant in the sad mood condition recalled exactly three. The effect of mood here is quite obvious. In reality, however, the data would probably look more like those in the two rightmost columns of Table 5.1 . Even in the happy mood condition, some participants would recall fewer happy memories because they have fewer to draw on, use less effective recall strategies, or are less motivated. And even in the sad mood condition, some participants would recall more happy childhood memories because they have more happy memories to draw on, they use more effective recall strategies, or they are more motivated. Although the mean difference between the two groups is the same as in the idealized data, this difference is much less obvious in the context of the greater variability in the data. Thus one reason researchers try to control extraneous variables is so their data look more like the idealized data in Table 5.1 , which makes the effect of the independent variable easier to detect (although real data never look quite that good).

| 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| 4 | 3 | 6 | 3 |

| 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| 4 | 3 | 4 | 0 |

| 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| 4 | 3 | 2 | 7 |

| 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 4 | 3 | 1 | 5 |

| 4 | 3 | 6 | 1 |

| 4 | 3 | 8 | 2 |

| = 4 | = 3 | = 4 | = 3 |

One way to control extraneous variables is to hold them constant. This technique can mean holding situation or task variables constant by testing all participants in the same location, giving them identical instructions, treating them in the same way, and so on. It can also mean holding participant variables constant. For example, many studies of language limit participants to right-handed people, who generally have their language areas isolated in their left cerebral hemispheres [1] . Left-handed people are more likely to have their language areas isolated in their right cerebral hemispheres or distributed across both hemispheres, which can change the way they process language and thereby add noise to the data.

In principle, researchers can control extraneous variables by limiting participants to one very specific category of person, such as 20-year-old, heterosexual, female, right-handed psychology majors. The obvious downside to this approach is that it would lower the external validity of the study—in particular, the extent to which the results can be generalized beyond the people actually studied. For example, it might be unclear whether results obtained with a sample of younger lesbian women would apply to older gay men. In many situations, the advantages of a diverse sample (increased external validity) outweigh the reduction in noise achieved by a homogeneous one.

Extraneous Variables as Confounding Variables

The second way that extraneous variables can make it difficult to detect the effect of the independent variable is by becoming confounding variables. A confounding variable is an extraneous variable that differs on average across levels of the independent variable (i.e., it is an extraneous variable that varies systematically with the independent variable). For example, in almost all experiments, participants’ intelligence quotients (IQs) will be an extraneous variable. But as long as there are participants with lower and higher IQs in each condition so that the average IQ is roughly equal across the conditions, then this variation is probably acceptable (and may even be desirable). What would be bad, however, would be for participants in one condition to have substantially lower IQs on average and participants in another condition to have substantially higher IQs on average. In this case, IQ would be a confounding variable.

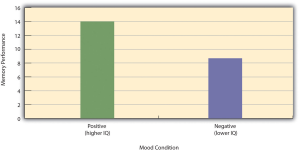

To confound means to confuse , and this effect is exactly why confounding variables are undesirable. Because they differ systematically across conditions—just like the independent variable—they provide an alternative explanation for any observed difference in the dependent variable. Figure 5.1 shows the results of a hypothetical study, in which participants in a positive mood condition scored higher on a memory task than participants in a negative mood condition. But if IQ is a confounding variable—with participants in the positive mood condition having higher IQs on average than participants in the negative mood condition—then it is unclear whether it was the positive moods or the higher IQs that caused participants in the first condition to score higher. One way to avoid confounding variables is by holding extraneous variables constant. For example, one could prevent IQ from becoming a confounding variable by limiting participants only to those with IQs of exactly 100. But this approach is not always desirable for reasons we have already discussed. A second and much more general approach—random assignment to conditions—will be discussed in detail shortly.

Treatment and Control Conditions

In psychological research, a treatment is any intervention meant to change people’s behavior for the better. This intervention includes psychotherapies and medical treatments for psychological disorders but also interventions designed to improve learning, promote conservation, reduce prejudice, and so on. To determine whether a treatment works, participants are randomly assigned to either a treatment condition , in which they receive the treatment, or a control condition , in which they do not receive the treatment. If participants in the treatment condition end up better off than participants in the control condition—for example, they are less depressed, learn faster, conserve more, express less prejudice—then the researcher can conclude that the treatment works. In research on the effectiveness of psychotherapies and medical treatments, this type of experiment is often called a randomized clinical trial .

There are different types of control conditions. In a no-treatment control condition , participants receive no treatment whatsoever. One problem with this approach, however, is the existence of placebo effects. A placebo is a simulated treatment that lacks any active ingredient or element that should make it effective, and a placebo effect is a positive effect of such a treatment. Many folk remedies that seem to work—such as eating chicken soup for a cold or placing soap under the bed sheets to stop nighttime leg cramps—are probably nothing more than placebos. Although placebo effects are not well understood, they are probably driven primarily by people’s expectations that they will improve. Having the expectation to improve can result in reduced stress, anxiety, and depression, which can alter perceptions and even improve immune system functioning (Price, Finniss, & Benedetti, 2008) [2] .

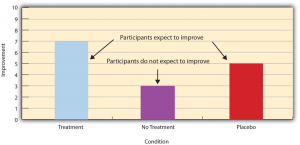

Placebo effects are interesting in their own right (see Note “The Powerful Placebo” ), but they also pose a serious problem for researchers who want to determine whether a treatment works. Figure 5.2 shows some hypothetical results in which participants in a treatment condition improved more on average than participants in a no-treatment control condition. If these conditions (the two leftmost bars in Figure 5.2 ) were the only conditions in this experiment, however, one could not conclude that the treatment worked. It could be instead that participants in the treatment group improved more because they expected to improve, while those in the no-treatment control condition did not.

Fortunately, there are several solutions to this problem. One is to include a placebo control condition , in which participants receive a placebo that looks much like the treatment but lacks the active ingredient or element thought to be responsible for the treatment’s effectiveness. When participants in a treatment condition take a pill, for example, then those in a placebo control condition would take an identical-looking pill that lacks the active ingredient in the treatment (a “sugar pill”). In research on psychotherapy effectiveness, the placebo might involve going to a psychotherapist and talking in an unstructured way about one’s problems. The idea is that if participants in both the treatment and the placebo control groups expect to improve, then any improvement in the treatment group over and above that in the placebo control group must have been caused by the treatment and not by participants’ expectations. This difference is what is shown by a comparison of the two outer bars in Figure 5.4 .

Of course, the principle of informed consent requires that participants be told that they will be assigned to either a treatment or a placebo control condition—even though they cannot be told which until the experiment ends. In many cases the participants who had been in the control condition are then offered an opportunity to have the real treatment. An alternative approach is to use a wait-list control condition , in which participants are told that they will receive the treatment but must wait until the participants in the treatment condition have already received it. This disclosure allows researchers to compare participants who have received the treatment with participants who are not currently receiving it but who still expect to improve (eventually). A final solution to the problem of placebo effects is to leave out the control condition completely and compare any new treatment with the best available alternative treatment. For example, a new treatment for simple phobia could be compared with standard exposure therapy. Because participants in both conditions receive a treatment, their expectations about improvement should be similar. This approach also makes sense because once there is an effective treatment, the interesting question about a new treatment is not simply “Does it work?” but “Does it work better than what is already available?

The Powerful Placebo

Many people are not surprised that placebos can have a positive effect on disorders that seem fundamentally psychological, including depression, anxiety, and insomnia. However, placebos can also have a positive effect on disorders that most people think of as fundamentally physiological. These include asthma, ulcers, and warts (Shapiro & Shapiro, 1999) [3] . There is even evidence that placebo surgery—also called “sham surgery”—can be as effective as actual surgery.

Medical researcher J. Bruce Moseley and his colleagues conducted a study on the effectiveness of two arthroscopic surgery procedures for osteoarthritis of the knee (Moseley et al., 2002) [4] . The control participants in this study were prepped for surgery, received a tranquilizer, and even received three small incisions in their knees. But they did not receive the actual arthroscopic surgical procedure. Note that the IRB would have carefully considered the use of deception in this case and judged that the benefits of using it outweighed the risks and that there was no other way to answer the research question (about the effectiveness of a placebo procedure) without it. The surprising result was that all participants improved in terms of both knee pain and function, and the sham surgery group improved just as much as the treatment groups. According to the researchers, “This study provides strong evidence that arthroscopic lavage with or without débridement [the surgical procedures used] is not better than and appears to be equivalent to a placebo procedure in improving knee pain and self-reported function” (p. 85).

- Knecht, S., Dräger, B., Deppe, M., Bobe, L., Lohmann, H., Flöel, A., . . . Henningsen, H. (2000). Handedness and hemispheric language dominance in healthy humans. Brain: A Journal of Neurology, 123 (12), 2512-2518. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/123.12.2512 ↵

- Price, D. D., Finniss, D. G., & Benedetti, F. (2008). A comprehensive review of the placebo effect: Recent advances and current thought. Annual Review of Psychology, 59 , 565–590. ↵

- Shapiro, A. K., & Shapiro, E. (1999). The powerful placebo: From ancient priest to modern physician . Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ↵

- Moseley, J. B., O’Malley, K., Petersen, N. J., Menke, T. J., Brody, B. A., Kuykendall, D. H., … Wray, N. P. (2002). A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. The New England Journal of Medicine, 347 , 81–88. ↵

A type of study designed specifically to answer the question of whether there is a causal relationship between two variables.

The variable the experimenter manipulates.

The variable the experimenter measures (it is the presumed effect).

The different levels of the independent variable to which participants are assigned.

Holding extraneous variables constant in order to separate the effect of the independent variable from the effect of the extraneous variables.

Any variable other than the dependent and independent variable.

Changing the level, or condition, of the independent variable systematically so that different groups of participants are exposed to different levels of that variable, or the same group of participants is exposed to different levels at different times.

An experiment design involving a single independent variable with two conditions.

When an experiment has one independent variable that is manipulated to produce more than two conditions.

An extraneous variable that varies systematically with the independent variable, and thus confuses the effect of the independent variable with the effect of the extraneous one.

Any intervention meant to change people’s behavior for the better.

The condition in which participants receive the treatment.

The condition in which participants do not receive the treatment.

An experiment that researches the effectiveness of psychotherapies and medical treatments.

The condition in which participants receive no treatment whatsoever.

A simulated treatment that lacks any active ingredient or element that is hypothesized to make the treatment effective, but is otherwise identical to the treatment.

An effect that is due to the placebo rather than the treatment.

Condition in which the participants receive a placebo rather than the treatment.

Condition in which participants are told that they will receive the treatment but must wait until the participants in the treatment condition have already received it.

Research Methods in Psychology Copyright © 2019 by Rajiv S. Jhangiani, I-Chant A. Chiang, Carrie Cuttler, & Dana C. Leighton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Conduct a Psychology Experiment

Conducting your first psychology experiment can be a long, complicated, and sometimes intimidating process. It can be especially confusing if you are not quite sure where to begin or which steps to take.

Like other sciences, psychology utilizes the scientific method and bases conclusions upon empirical evidence. When conducting an experiment, it is important to follow the seven basic steps of the scientific method:

- Ask a testable question

- Define your variables

- Conduct background research

- Design your experiment

- Perform the experiment

- Collect and analyze the data

- Draw conclusions

- Share the results with the scientific community

At a Glance

It's important to know the steps of the scientific method if you are conducting an experiment in psychology or other fields. The processes encompasses finding a problem you want to explore, learning what has already been discovered about the topic, determining your variables, and finally designing and performing your experiment. But the process doesn't end there! Once you've collected your data, it's time to analyze the numbers, determine what they mean, and share what you've found.

Find a Research Problem or Question

Picking a research problem can be one of the most challenging steps when you are conducting an experiment. After all, there are so many different topics you might choose to investigate.

Are you stuck for an idea? Consider some of the following:

Investigate a Commonly Held Belief

Folk knowledge is a good source of questions that can serve as the basis for psychological research. For example, many people believe that staying up all night to cram for a big exam can actually hurt test performance.

You could conduct a study to compare the test scores of students who stayed up all night with the scores of students who got a full night's sleep before the exam.

Review Psychology Literature

Published studies are a great source of unanswered research questions. In many cases, the authors will even note the need for further research. Find a published study that you find intriguing, and then come up with some questions that require further exploration.

Think About Everyday Problems

There are many practical applications for psychology research. Explore various problems that you or others face each day, and then consider how you could research potential solutions. For example, you might investigate different memorization strategies to determine which methods are most effective.

Define Your Variables

Variables are anything that might impact the outcome of your study. An operational definition describes exactly what the variables are and how they are measured within the context of your study.

For example, if you were doing a study on the impact of sleep deprivation on driving performance, you would need to operationally define sleep deprivation and driving performance .

An operational definition refers to a precise way that an abstract concept will be measured. For example, you cannot directly observe and measure something like test anxiety . You can, however, use an anxiety scale and assign values based on how many anxiety symptoms a person is experiencing.

In this example, you might define sleep deprivation as getting less than seven hours of sleep at night. You might define driving performance as how well a participant does on a driving test.

What is the purpose of operationally defining variables? The main purpose is control. By understanding what you are measuring, you can control for it by holding the variable constant between all groups or manipulating it as an independent variable .

Develop a Hypothesis

The next step is to develop a testable hypothesis that predicts how the operationally defined variables are related. In the recent example, the hypothesis might be: "Students who are sleep-deprived will perform worse than students who are not sleep-deprived on a test of driving performance."

Null Hypothesis

In order to determine if the results of the study are significant, it is essential to also have a null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is the prediction that one variable will have no association to the other variable.

In other words, the null hypothesis assumes that there will be no difference in the effects of the two treatments in our experimental and control groups .

The null hypothesis is assumed to be valid unless contradicted by the results. The experimenters can either reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis or not reject the null hypothesis.

It is important to remember that not rejecting the null hypothesis does not mean that you are accepting the null hypothesis. To say that you are accepting the null hypothesis is to suggest that something is true simply because you did not find any evidence against it. This represents a logical fallacy that should be avoided in scientific research.

Conduct Background Research

Once you have developed a testable hypothesis, it is important to spend some time doing some background research. What do researchers already know about your topic? What questions remain unanswered?

You can learn about previous research on your topic by exploring books, journal articles, online databases, newspapers, and websites devoted to your subject.

Reading previous research helps you gain a better understanding of what you will encounter when conducting an experiment. Understanding the background of your topic provides a better basis for your own hypothesis.

After conducting a thorough review of the literature, you might choose to alter your own hypothesis. Background research also allows you to explain why you chose to investigate your particular hypothesis and articulate why the topic merits further exploration.

As you research the history of your topic, take careful notes and create a working bibliography of your sources. This information will be valuable when you begin to write up your experiment results.

Select an Experimental Design

After conducting background research and finalizing your hypothesis, your next step is to develop an experimental design. There are three basic types of designs that you might utilize. Each has its own strengths and weaknesses:

Pre-Experimental Design

A single group of participants is studied, and there is no comparison between a treatment group and a control group. Examples of pre-experimental designs include case studies (one group is given a treatment and the results are measured) and pre-test/post-test studies (one group is tested, given a treatment, and then retested).

Quasi-Experimental Design

This type of experimental design does include a control group but does not include randomization. This type of design is often used if it is not feasible or ethical to perform a randomized controlled trial.

True Experimental Design

A true experimental design, also known as a randomized controlled trial, includes both of the elements that pre-experimental designs and quasi-experimental designs lack—control groups and random assignment to groups.

Standardize Your Procedures

In order to arrive at legitimate conclusions, it is essential to compare apples to apples.

Each participant in each group must receive the same treatment under the same conditions.

For example, in our hypothetical study on the effects of sleep deprivation on driving performance, the driving test must be administered to each participant in the same way. The driving course must be the same, the obstacles faced must be the same, and the time given must be the same.

Choose Your Participants

In addition to making sure that the testing conditions are standardized, it is also essential to ensure that your pool of participants is the same.

If the individuals in your control group (those who are not sleep deprived) all happen to be amateur race car drivers while your experimental group (those that are sleep deprived) are all people who just recently earned their driver's licenses, your experiment will lack standardization.

When choosing subjects, there are some different techniques you can use.

Simple Random Sample

In a simple random sample, the participants are randomly selected from a group. A simple random sample can be used to represent the entire population from which the representative sample is drawn.

Drawing a simple random sample can be helpful when you don't know a lot about the characteristics of the population.

Stratified Random Sample

Participants must be randomly selected from different subsets of the population. These subsets might include characteristics such as geographic location, age, sex, race, or socioeconomic status.

Stratified random samples are more complex to carry out. However, you might opt for this method if there are key characteristics about the population that you want to explore in your research.

Conduct Tests and Collect Data

After you have selected participants, the next steps are to conduct your tests and collect the data. Before doing any testing, however, there are a few important concerns that need to be addressed.

Address Ethical Concerns

First, you need to be sure that your testing procedures are ethical . Generally, you will need to gain permission to conduct any type of testing with human participants by submitting the details of your experiment to your school's Institutional Review Board (IRB), sometimes referred to as the Human Subjects Committee.

Obtain Informed Consent

After you have gained approval from your institution's IRB, you will need to present informed consent forms to each participant. This form offers information on the study, the data that will be gathered, and how the results will be used. The form also gives participants the option to withdraw from the study at any point in time.

Once this step has been completed, you can begin administering your testing procedures and collecting the data.

Analyze the Results

After collecting your data, it is time to analyze the results of your experiment. Researchers use statistics to determine if the results of the study support the original hypothesis and if the results are statistically significant.

Statistical significance means that the study's results are unlikely to have occurred simply by chance.

The types of statistical methods you use to analyze your data depend largely on the type of data that you collected. If you are using a random sample of a larger population, you will need to utilize inferential statistics.

These statistical methods make inferences about how the results relate to the population at large.

Because you are making inferences based on a sample, it has to be assumed that there will be a certain margin of error. This refers to the amount of error in your results. A large margin of error means that there will be less confidence in your results, while a small margin of error means that you are more confident that your results are an accurate reflection of what exists in that population.

Share Your Results After Conducting an Experiment

Your final task in conducting an experiment is to communicate your results. By sharing your experiment with the scientific community, you are contributing to the knowledge base on that particular topic.

One of the most common ways to share research results is to publish the study in a peer-reviewed professional journal. Other methods include sharing results at conferences, in book chapters, or academic presentations.

In your case, it is likely that your class instructor will expect a formal write-up of your experiment in the same format required in a professional journal article or lab report :

- Introduction

- Tables and figures

What This Means For You

Designing and conducting a psychology experiment can be quite intimidating, but breaking the process down step-by-step can help. No matter what type of experiment you decide to perform, always check with your instructor and your school's institutional review board for permission before you begin.

NOAA SciJinks. What is the scientific method? .

Nestor, PG, Schutt, RK. Research Methods in Psychology . SAGE; 2015.

Andrade C. A student's guide to the classification and operationalization of variables in the conceptualization and eesign of a clinical study: Part 2 . Indian J Psychol Med . 2021;43(3):265-268. doi:10.1177/0253717621996151

Purna Singh A, Vadakedath S, Kandi V. Clinical research: A review of study designs, hypotheses, errors, sampling types, ethics, and informed consent . Cureus . 2023;15(1):e33374. doi:10.7759/cureus.33374

Colby College. The Experimental Method .

Leite DFB, Padilha MAS, Cecatti JG. Approaching literature review for academic purposes: The Literature Review Checklist . Clinics (Sao Paulo) . 2019;74:e1403. doi:10.6061/clinics/2019/e1403

Salkind NJ. Encyclopedia of Research Design . SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2010. doi:10.4135/9781412961288

Miller CJ, Smith SN, Pugatch M. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs in implementation research . Psychiatry Res . 2020;283:112452. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.06.027

Nijhawan LP, Manthan D, Muddukrishna BS, et. al. Informed consent: Issues and challenges . J Adv Pharm Technol Rese . 2013;4(3):134-140. doi:10.4103/2231-4040.116779

Serdar CC, Cihan M, Yücel D, Serdar MA. Sample size, power and effect size revisited: simplified and practical approaches in pre-clinical, clinical and laboratory studies . Biochem Med (Zagreb) . 2021;31(1):010502. doi:10.11613/BM.2021.010502

American Psychological Association. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). Washington DC: The American Psychological Association; 2019.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Laboratory Experimentation

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2020

- pp 2559–2562

- Cite this reference work entry

- Katrin Bittrich 3 &

- Torsten Schubert 3

20 Accesses

In laboratory experimentation the causal influence of at least one actively manipulated independent variable on at least on dependent variable is tested in a controlled envorinment.

Introduction

The main objective of the experimental approach is to causally relate changes in one or more independent variables to changes in one or more dependent variables. The condition assignment is usually randomized, and researchers aim to eliminate or control the potential effect(s) of extraneous variables on the data of interest. By analyzing the manifestation of individual differences in the data variability with elaborated methods, the advantages of an experimental approach can be combined with research methods designed to understand the individual realization of the investigated phenomena and their emergence in the corresponding experimental condition.

Experimental Method

Scientific research aims to gather information objectively and systematically such that valid conclusions can be...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bittrich, K., & Blankenberger, S. (2011). Experimentelle Psychologie: Experimente planen realisieren, präsentieren . Weinheim: Beltz.

Google Scholar

Hager, W. (1987). Grundlagen einer Versuchsplanung zur Prüfung empirischer Hypothesen der Psychologie. In G. Lüer (Ed.), Allgemeine Experimentelle Psychologie (pp. 43–253). Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer Verlag.

Iacobucci, D., Posavach, S. S., Kardes, F. R., Schneider, M. J., & Popovich, D. L. (2015). Toward a more nuanced understanding of the statistical properties of a median split. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25 , 666–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2015.04.004 .

Article Google Scholar

Myers, A., & Hansen, C. (2012). Experimental psychology (7th ed.). Wadsworth: Cengage Learning.

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., MacCallum, R. C., & Nicewander, W. A. (2005). Use of the extreme groups approach: A critical reexamination and new recommendations. Psychological Methods, 10 , 178–192. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.10.2.178 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Revelle, W. (2007). Experimental approaches to the study of personality. In R. W. Robins, R. C. Fraley, & R. F. Krueger (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in personality psychology . New York: The Guilford Press.

Revelle, W., Condon, D. M., & Wilt, J. (2011). Methodological advances in differential psychology. In T. Chamorro-Premuzic, S. von Stumm, & A. Furnham (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of individual differences . Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Rucker, D. D., McShane, B. B., & Preacher, K. J. (2015). A researcher's guide to regression, discretization, and median splits of continuous variables. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25 (4), 666–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2015.04.004 .

Rusting, C. L., & Larsen, R. J. (1998). Personality and cognitive processing of affective information. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24 , 200–2013. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167298242008 .

Shadish, W. R., Cook T. D., & Campbell D. T. (2001). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference (2nd ed.). Wadsworth: Cengage Learning.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg, Halle, Germany

Katrin Bittrich & Torsten Schubert

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Katrin Bittrich .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Oakland University, Rochester, MI, USA

Virgil Zeigler-Hill

Todd K. Shackelford

Section Editor information

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Matthias Ziegler

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Bittrich, K., Schubert, T. (2020). Laboratory Experimentation. In: Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T.K. (eds) Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24612-3_1319

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24612-3_1319

Published : 22 April 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-24610-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-24612-3

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

7 Advantages and Disadvantages of Experimental Research

There are multiple ways to test and do research on new ideas, products, or theories. One of these ways is by experimental research. This is when the researcher has complete control over one set of the variable, and manipulates the others. A good example of this is pharmaceutical research. They will administer the new drug to one group of subjects, and not to the other, while monitoring them both. This way, they can tell the true effects of the drug by comparing them to people who are not taking it. With this type of research design, only one variable can be tested, which may make it more time consuming and open to error. However, if done properly, it is known as one of the most efficient and accurate ways to reach a conclusion. There are other things that go into the decision of whether or not to use experimental research, some bad and some good, let’s take a look at both of these.

The Advantages of Experimental Research

1. A High Level Of Control With experimental research groups, the people conducting the research have a very high level of control over their variables. By isolating and determining what they are looking for, they have a great advantage in finding accurate results.

2. Can Span Across Nearly All Fields Of Research Another great benefit of this type of research design is that it can be used in many different types of situations. Just like pharmaceutical companies can utilize it, so can teachers who want to test a new method of teaching. It is a basic, but efficient type of research.

3. Clear Cut Conclusions Since there is such a high level of control, and only one specific variable is being tested at a time, the results are much more relevant than some other forms of research. You can clearly see the success, failure, of effects when analyzing the data collected.