Home Blog Education How to Prepare Your Scientific Presentation

How to Prepare Your Scientific Presentation

Since the dawn of time, humans were eager to find explanations for the world around them. At first, our scientific method was very simplistic and somewhat naive. We observed and reflected. But with the progressive evolution of research methods and thinking paradigms, we arrived into the modern era of enlightenment and science. So what represents the modern scientific method and how can you accurately share and present your research findings to others? These are the two fundamental questions we attempt to answer in this post.

What is the Scientific Method?

To better understand the concept, let’s start with this scientific method definition from the International Encyclopedia of Human Geography :

The scientific method is a way of conducting research, based on theory construction, the generation of testable hypotheses, their empirical testing, and the revision of theory if the hypothesis is rejected.

Essentially, a scientific method is a cumulative term, used to describe the process any scientist uses to objectively interpret the world (and specific phenomenon) around them.

The scientific method is the opposite of beliefs and cognitive biases — mostly irrational, often unconscious, interpretations of different occurrences that we lean on as a mental shortcut.

The scientific method in research, on the contrary, forces the thinker to holistically assess and test our approaches to interpreting data. So that they could gain consistent and non-arbitrary results.

The common scientific method examples are:

- Systematic observation

- Experimentation

- Inductive and deductive reasoning

- Formation and testing of hypotheses and theories

All of the above are used by both scientists and businesses to make better sense of the data and/or phenomenon at hand.

The Evolution of the Scientific Method

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , ancient thinkers such as Plato and Aristotle are believed to be the forefathers of the scientific method. They were among the first to try to justify and refine their thought process using the scientific method experiments and deductive reasoning.

Both developed specific systems for knowledge acquisition and processing. For example, the Platonic way of knowledge emphasized reasoning as the main method for learning but downplayed the importance of observation. The Aristotelian corpus of knowledge, on the contrary, said that we must carefully observe the natural world to discover its fundamental principles.

In medieval times, thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas, Roger Bacon, and Andreas Vesalius among many others worked on further clarifying how we can obtain proven knowledge through observation and induction.

The 16th–18th centuries are believed to have given the greatest advances in terms of scientific method application. We, humans, learned to better interpret the world around us from mechanical, biological, economic, political, and medical perspectives. Thinkers such as Galileo Galilei, Francis Bacon, and their followers also increasingly switched to a tradition of explaining everything through mathematics, geometry, and numbers.

Up till today, mathematical and mechanical explanations remain the core parts of the scientific method.

Why is the Scientific Method Important Today?

Because our ancestors didn’t have as much data as we do. We now live in the era of paramount data accessibility and connectivity, where over 2.5 quintillions of data are produced each day. This has tremendously accelerated knowledge creation.

But, at the same time, such overwhelming exposure to data made us more prone to external influences, biases, and false beliefs. These can jeopardize the objectivity of any research you are conducting.

Scientific findings need to remain objective, verifiable, accurate, and consistent. Diligent usage of scientific methods in modern business and science helps ensure proper data interpretation, results replication, and undisputable validity.

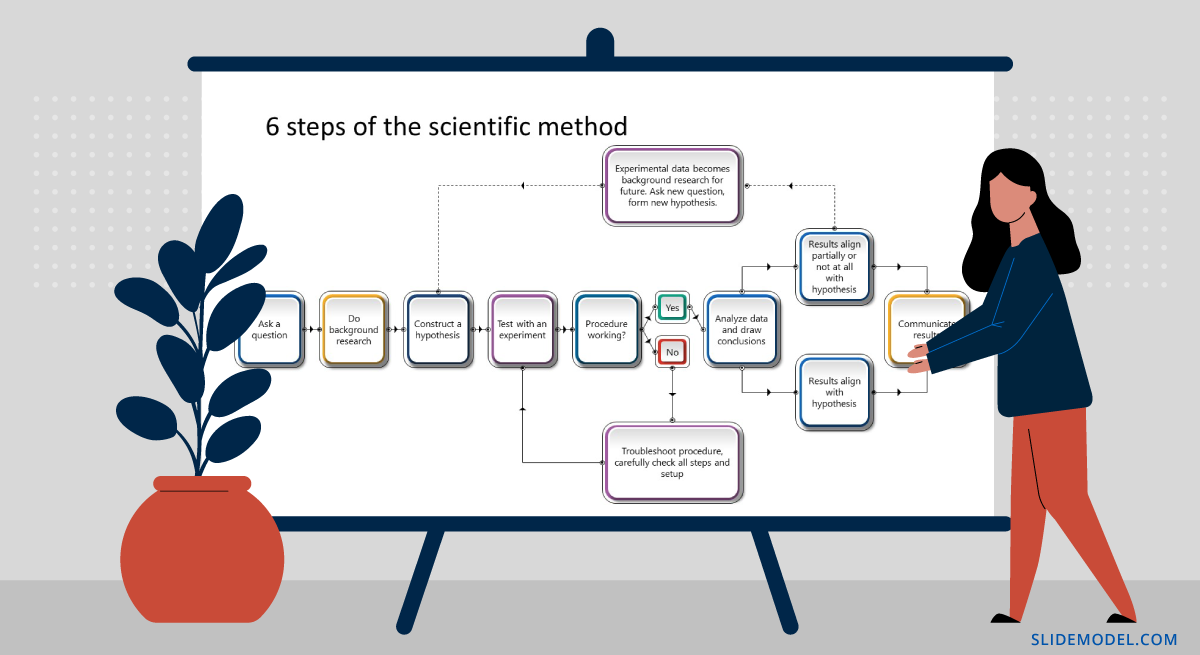

6 Steps of the Scientific Method

Over the course of history, the scientific method underwent many interactions. Yet, it still carries some of the integral steps our ancestors used to analyze the world such as observation and inductive reasoning. However, the modern scientific method steps differ a bit.

1. Make an Observation

An observation serves as a baseline for your research. There are two important characteristics for a good research observation:

- It must be objective, not subjective.

- It must be verifiable, meaning others can say it’s true or false with this.

For example, This apple is red (objective/verifiable observation). This apple is delicious (subjective, harder-to-verify observation).

2. Develop a Hypothesis

Observations tell us about the present or past. But the goal of science is to glean in the future. A scientific hypothesis is based on prior knowledge and produced through reasoning as an attempt to descriptive a future event.

Here are characteristics of a good scientific hypothesis:

- General and tentative idea

- Agrees with all available observations

- Testable and potentially falsifiable

Remember: If we state our hypothesis to indicate there is no effect, our hypothesis is a cause-and-effect relationship . A hypothesis, which asserts no effect, is called a null hypothesis.

3. Make a Prediction

A hypothesis is a mental “launchpad” for predicting the existence of other phenomena or quantitative results of new observations.

Going back to an earlier example here’s how to turn it into a hypothesis and a potential prediction for proving it. For example: If this apple is red, other apples of this type should be red too.

Your goal is then to decide which variables can help you prove or disprove your hypothesis and prepare to test these.

4. Perform an Experiment

Collect all the information around variables that will help you prove or disprove your prediction. According to the scientific method, a hypothesis has to be discarded or modified if its predictions are clearly and repeatedly incompatible with experimental results.

Yes, you may come up with an elegant theory. However, if your hypothetical predictions cannot be backed by experimental results, you cannot use them as a valid explanation of the phenomenon.

5. Analyze the Results of the Experiment

To come up with proof for your hypothesis, use different statistical analysis methods to interpret the meaning behind your data.

Remember to stay objective and emotionally unattached to your results. If 95 apples turned red, but 5 were yellow, does it disprove your hypothesis? Not entirely. It may mean that you didn’t account for all variables and must adapt the parameters of your experiment.

Here are some common data analysis techniques, used as a part of a scientific method:

- Statistical analysis

- Cause and effect analysis (see cause and effect analysis slides )

- Regression analysis

- Factor analysis

- Cluster analysis

- Time series analysis

- Diagnostic analysis

- Root cause analysis (see root cause analysis slides )

6. Draw a Conclusion

Every experiment has two possible outcomes:

- The results correspond to the prediction

- The results disprove the prediction

If that’s the latter, as a scientist you must discard the prediction then and most likely also rework the hypothesis based on it.

How to Give a Scientific Presentation to Showcase Your Methods

Whether you are doing a poster session, conference talk, or follow-up presentation on a recently published journal article, most of your peers need to know how you’ve arrived at the presented conclusions.

In other words, they will probe your scientific method for gaps to ensure that your results are fair and possible to replicate. So that they could incorporate your theories in their research too. Thus your scientific presentation must be sharp, on-point, and focus clearly on your research approaches.

Below we propose a quick framework for creating a compelling scientific presentation in PowerPoint (+ some helpful templates!).

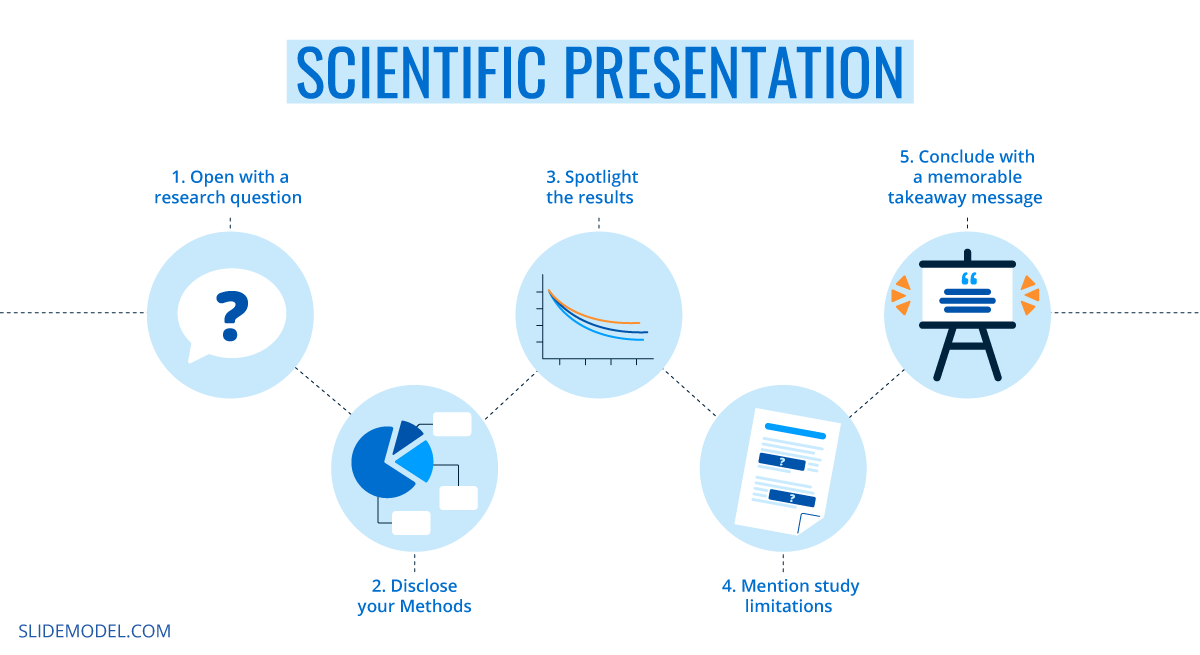

1. Open with a Research Question

Here’s how to start a scientific presentation with ease: share your research question. On the first slide, briefly recap how your thought process went. Briefly state what was the underlying aim of your research: Share your main hypothesis, mention if you could prove or disprove them.

It might be tempting to pack a lot of ideas into your first slide but don’t. Keep the opening of your presentation short to pique the audience’s initial interest and set the stage for the follow-up narrative.

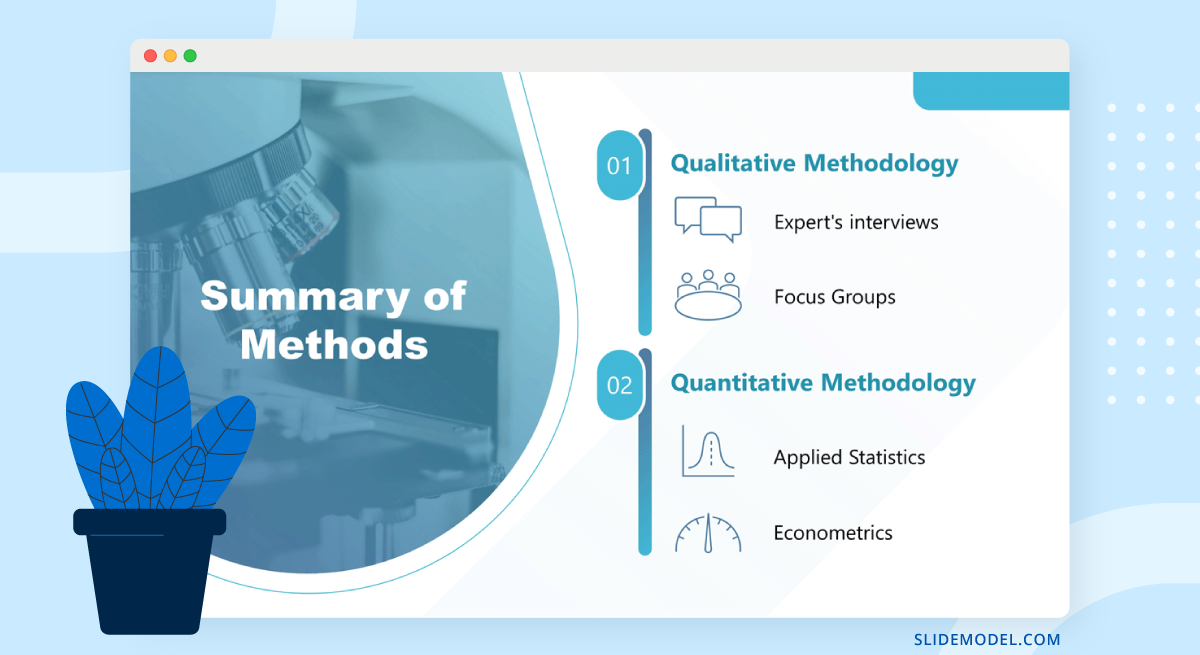

2. Disclose Your Methods

Whether you are doing a science poster presentation or conference talk, many audience members would be curious to understand how you arrived at your results. Deliver this information at the beginning of your presentation to avoid any ambiguities.

Here’s how to organize your science methods on a presentation:

- Do not use bullet points or full sentences. Use diagrams and structured images to list the methods

- Use visuals and iconography to use metaphors where possible.

- Organize your methods by groups e.g. quantifiable and non-quantifiable

Finally, when you work on visuals for your presentation — charts, graphs, illustrations, etc. — think from the perspective of a subject novice. Does the image really convey the key information around the subject? Does it help break down complex ideas?

3. Spotlight the Results

Obviously, the research results will be your biggest bragging right. However, don’t over-pack your presentation with a long-winded discussion of your findings and how revolutionary these may be for the community.

Rather than writing a wall of text, do this instead:

- Use graphs with large axis values/numbers to showcase the findings in great detail

- Prioritize formats that are known to everybody (e.g. odds ratios, Kaplan Meier curves, etc.)

- Do not include more than 5 lines of plain text per slide

Overall, when you feel that the results slide gets too cramped, it’s best to move the data to a new one.

Also, as you work on organizing data on your scientific presentation PowerPoint template , think if there are obvious limitations and gaps. If yes, make sure you acknowledge them during your speech.

4. Mention Study Limitations

The scientific method mandates objectivity. That’s why every researcher must clearly state what was excluded from their study. Remember: no piece of scientific research is truly universal and has certain boundaries. However, when you fail to personally state those, others might struggle to draw the line themselves and replicate your results. Then, if they fail to do so, they’d question the viability of your research.

5. Conclude with a Memorable Takeaway Message

Every experienced speaker will tell you that the audience best retains the information they hear first and last. Most people will attend more than one scientific presentation during the day.

So if you want the audience to better remember your talk, brainstorm a take-home message for the last slide of your presentation. Think of your last slide texts as an elevator pitch — a short, concluding message, summarizing your research.

To Conclude

Today we have no shortage of research and scientific methods for testing and proving our hypothesis. However, unlike our ancestors, most scientists experience deeper scrutiny when it comes to presenting and explaining their findings to others. That’s why it’s important to ensure that your scientific presentation clearly relays the aim, vector, and thought process behind your research.

Like this article? Please share

Education, Presentation Ideas, Presentation Skills, Presentation Tips Filed under Education

Related Articles

Filed under Business • November 6th, 2024

Meeting Agenda Examples: Guide + PPT Templates

Are you looking for creative agenda examples for your presentations? If so, we invite you to discover the secrets to creating a professional agenda slide.

Filed under Presentation Ideas • October 23rd, 2024

Formal vs Informal Presentation: Understanding the Differences

Learn the differences between formal and informal presentations and how to transition smoothly. PPT templates and tips here!

Filed under Design • October 22nd, 2024

The Rules of PowerPoint Presentations: Creating Effective Slides

Create powerful slide decks by mastering the rules of PowerPoint presentations. Must-known tips, guidance, and examples.

Leave a Reply

- Enterprise Custom Courses

- Build Your Own Courses

- Help Center

- Clinical Trial Recruitment

- Pharmaceutical Marketing

- Health Department Resources

- Patient Education

- Research Presentation

- Remote Monitoring

- Health Literacy & SciComm

- Student Education & Higher Ed

- Individual Learning

- Member Directory

- Community Chats on Slack

- SciComm Program

- The Story-Driven Method

- The Instructional Method

How to Create an Engaging Science Presentation: A Quick Guide

We’ve all been there – rushing to put slides together for an upcoming talk, filling them with bullet points and text that we want to remember to cover. We aren’t sure exactly what the audience will want to know or how much detail to include, so we default to putting ALL the details in that might be needed. But such efforts often result in presentations that are too long, too confusing, and difficult for both ourselves and our audiences to navigate.

Today I gave a workshop to public health graduate students about how to create more engaging science presentations and talks. I’ve summarized the main takeaways below. I hope this quick guide will be useful to you as you prepare for your next science talk or presentation!

The best science talks start with a process of simplifying – peeling back the layers of information and detail to get at the one core idea that you want to communicate. Over the course of your talk, you may present 2-3 key messages that relate to, demonstrate, provide examples of or underpin this idea. (Three is a nice round number of messages or takeaways that your audience will be able to remember!) But stick to one big idea. Trying to communicate too much in a presentation or talk will overwhelm your audience, and they may walk away without a good memory of any of the ideas you presented.

Once you’ve settled on your one big idea, you can develop a theme that will pervade every aspect of your talk. This theme might be a defining element of your big idea and something that can tie all of your data or talking points together. Your theme should inform the examples, anecdotes and analogies that you use to make the science concepts you present more accessible. It should also inform your slides’ very design – the colors, visuals, layout and content flow.

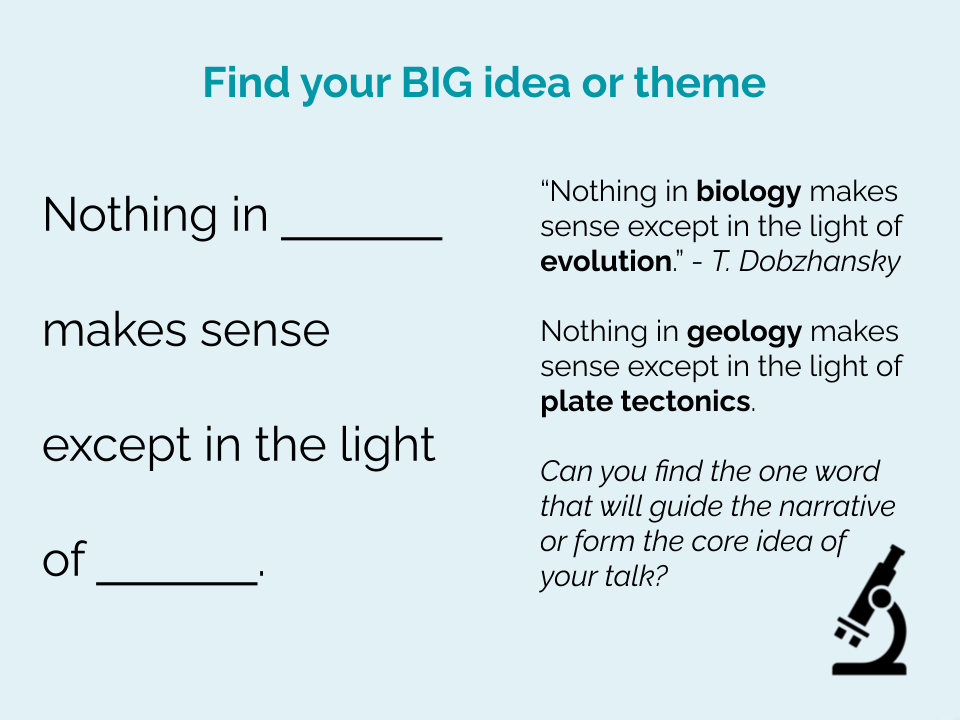

If you have trouble identifying your big idea and your theme, you can try using what scientist and science author Randy Olson calls the “Dobzhansky Template.” Fill in the blanks of this statement: “ Nothing in [your talk topic, research topic or big idea] makes sense, except in the light of [your theme!] .”

Here’s an example for you: “Nothing in the creation of engaging science talks makes sense except in the light of people’s need for personal connection .” With this statement, I’m identifying a key aspect, a unifying theme, for my talk (or blog post) on how to create engaging science talks. We all crave personal connection. Yes, even to the speakers of science talks we listen to! What does this mean in terms of what we want or expect from these speakers? It means we want storytelling . We want to hear their stories, know their background, hear about their struggles and triumphs! We want to be able to step into their shoes and see what they saw. We want to interact with them.

Tell a Story

Narratives engage more than facts. By telling a story , using suspense and characters to pull people through your presentation, you will capture and keep their attention for longer. People also remember information presented in a story format better than they do information presented as disparate facts or bullet points.

“Story is a pull strategy. If your story is good enough, people—of their own free will—come to the conclusion they can trust you and the message you bring.” – Annette Simmons

Storytelling is a powerful science communication tool. In storytelling, both the storyteller and the listener or reader contribute to the story’s meaning through their interpretations, feelings and emotions. Liz Neeley, former executive director of The Story Collider, once said: “Science communicators frequently fail to understand that a feeling is almost never conquered with a fact.”

Stories are exciting. They elicit emotions. They help foster a personal connection between the storyteller and the listener, and a connection between the listener and the topic, characters or ideas presented in the story.

But what IS a story? As humans, we excel at recognizing a story when we hear one, but defining a story’s key characteristics is more difficult than you might think. If you ask anyone to explain what makes for a good story, they likely will have a hard time explaining it.

In her fantastic book Wired for Story , Lisa Cron starts by explaining what a story is NOT.

It is not plot – that is just what happens in the story.

It is not characters , although characters are critical components of storytelling, even if they are not human or even alive. Cells and molecules could be the characters of your next science talk!

It is not suspense or conflict , although these elements get us closer to what defines a good story. But just because your talk builds suspense does not necessarily make it an engaging story. What if we don’t identify with your characters?

The truth is that the key defining element of story is internal change . Think of how every Aesop’s fable communicates a moral or lesson that the main character learned from some journey. As Lisa Cron writes, “A story is how what happens affects someone who is trying to achieve what turns out to be a difficult goal, and how he or she changes as a result.” The key here is the part about “how he or she changes.” A great story calls characters to a great adventure, but the adventure doesn’t leave them just as they were before. The adventure – like a scientific discovery that took years of experimentation (and failure) in the lab – leads to an internal change, in perspective or knowledge or behavior, as a result of conflicts overcome.

This is the secret of storytelling. A story asks characters to change and grow, and so the scientists in our stories must change and grow, discover new things about themselves and overcome challenges that force them to adopt new perspectives. So if you are giving a science talk about your own research, this might look like telling stories about your own struggles, growths and changes in perspective as you made your journey to discovery!

How can you bring a story of internal change to your next science presentation or talk?

What is one of the most common mistakes people make when creating slides to accompany a science talk? They use WAY too much text, and they use visuals as an afterthought. Worse yet, they use visuals that are copyrighted without attribution. They use stock imagery that reinforces stereotypes. They use visuals pasted from a Google search that don’t help the viewer understand or interpret what is said or written on the slides.

Visuals can be a powerful tool to advance audience learning or engagement during your science talks. You can use visuals to provide concrete examples of concepts you are talking about. You can use imagery that sparks thought or emotion. You can use visuals that reinforce your BIG idea or the theme of your talk, in a way that will make your talk more memorable for them. Yes, you might need to use a scientific figure, graph, chart or data visualization here and there if you are giving a more technical scientific talk, and that’s ok as long as you also talk the audience through this visual. Don’t assume they can listen to you talk about something different while also taking the time to interpret the message in this graphic or visualization – they can’t.

The same goes for text. You are demanding way too much brainpower of your audience to expect them to listen to you while also reading your slides. And if you are saying the same things as are written on your slides, they will grow bored. Simple visual aids used the right way, however, can delight your audience and help them better understand what you are saying.

Consider working with a professional artist or designer to create visuals for the slides of your next science talk! They excel at creating visuals that capture people’s attention, curiosity and emotions. And if you do this, your visuals will perfectly match what you are trying to communicate in words, boosting learning and understanding.

Foster Interaction

A good science talk or presentation gives the audience opportunities to interact with you! This could be through questions, activities, discussions or thought experiments. Let the audience explore your data or interpretations with you. They will be more engaged and likely trust you more as a result, because they felt heard .

Personalize!

Most great science speakers make themselves vulnerable in a way – they tell personal stories of struggles, growth and discovery. Personal stories are engaging. They also help the audience care about what the speaker has to say.

It can be scary to talk about yourself, especially for a scientist who has been trained to focus solely on the data. But the humans listening to your talk or presentation crave human connection. They will also grab hold of anything that helps them better relate to you. Give them that in the form of personal stories of obstacles overcome, of personal lessons learned, of work-life balance, of your fears and passions. Better yet, tell personal stories that reinforce your theme and show the power of your big idea!

Do you have other strategies for how you make your science talks and presentations more engaging? Let me know in the comments below!

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

About the author: paige jarreau.

Related Posts

Una actividad práctica para ayudarte a comunicar la ciencia de forma culturalmente relevante

The Power of SciComm in Combatting Mental Health Stigma

Make your scicomm more culturally relevant: a practice activity.

Communicating About Postpartum Depression

Science Communication and Genetic Counselling

Creating Analogies: Elevate Your Science with a Lifeology Course

- Program Design

- Peer Mentors

- Excelling in Graduate School

- Oral Communication

- Written communication

- About Climb

Designing PowerPoint Slides for a Scientific Presentation

In the video below, we show you the key principles for designing effective PowerPoint slides for a scientific presentation.

Using examples from actual science presentations, we illustrate the following principles:

- Create each slide as a single message unit

- Explicitly state that single message on the slide

- Avoid bullet points-opt for word tables

- Use simple diagrams

- Signal steps in biological processes

- Annotate key biological structures

- Annotate data in tables and graphs

You can also find this video, and others related to scientific communication, at the CLIMB youtube channel: http://www.youtube.com/climbprogram

Quick Links

Northwestern bioscience programs.

- Biomedical Engineering (BME)

- Chemical and Biological Engineering (ChBE)

- Driskill Graduate Program in the Life Sciences (DGP)

- Interdepartmental Biological Sciences (IBiS)

- Northwestern University Interdepartmental Neuroscience (NUIN)

- Campus Emergency Information

- Contact Northwestern University

- Report an Accessibility Issue

- University Policies

- Northwestern Home

- Northwestern Calendar: PlanIt Purple

- Northwestern Search

Chicago: 420 East Superior Street, Rubloff 6-644, Chicago, IL 60611 312-503-8286

How to make a scientific PowerPoint presentation [Expert Guide]

Recently, I was talking to a client from a renowned pharmaceutical company who asked a crucial question: "How can we make our scientific PowerPoint presentations more engaging and effective?" It struck me that many others might have the same question.

Therefore, I decided to write this blog to share insights on creating a compelling scientific PowerPoint presentation. Whether you're presenting at a conference, pitching to potential investors, or sharing findings with your team, mastering the art of scientific presentations is essential.

What are scientific PowerPoint presentations?

A scientific PowerPoint presentation is a unique blend of rigorous data and engaging storytelling. The goal is to convey complex information in a way that is easy to understand and visually appealing. Here’s a step-by-step guide to help you achieve that.

How to make a scientific presentation?

1. start with a strong title slide.

Your title slide is the first thing your audience will see, so it must be impactful. Include the title of your presentation, your name, and your affiliation. Adding a relevant image or graphic can also help capture attention. Make sure the title is clear and concise.

Example: Title: "Innovative Approaches in Cancer Research" Subtitle: "A Study on Targeted Therapy" Presented by: Dr. John Smith, Ph.D. Affiliation: XYZ Pharmaceutical Company

2. Outline Your Presentation

An outline slide at the beginning of your presentation helps your audience understand what to expect. This slide should include the main sections of your presentation, such as Introduction, Methodology, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion.

Example: Outline:

Introduction

Methodology

3. Craft a Compelling Introduction

The introduction sets the stage for your presentation. Start with a brief overview of the topic and why it’s important. Provide some background information and state the objectives of your study or research. Use visuals to support your points and keep your audience engaged.

Example: "Today, we're exploring innovative approaches in cancer research, focusing on targeted therapy. Cancer remains one of the leading causes of death worldwide, and developing more effective treatments is crucial."

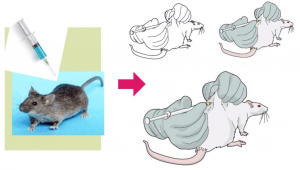

4. Present Your Methodology Clearly

The methodology section should explain how you conducted your research. Use simple language and avoid jargon as much as possible. Include diagrams, flowcharts, or images to illustrate your research process.

Example: "To study the effects of targeted therapy on cancer cells, we conducted a series of experiments using XYZ techniques. This involved cultivating cancer cell lines, applying targeted treatments, and monitoring cell responses over a 12-month period."

5. Showcase Your Results with Visuals

The results section is the core of your scientific PowerPoint presentation. Present your data clearly using charts, graphs, and tables. Ensure that each visual is easy to read and understand. Highlight key findings and use bullet points to summarize important information.

Example: "Our results showed a significant reduction in tumor size in mice treated with the new targeted therapy. As illustrated in the graph, the treatment group exhibited a 50% decrease in tumor size compared to the control group."

6. Discuss the Implications

In the discussion section, interpret your results and explain their significance. Discuss how your findings contribute to the existing body of knowledge and what implications they have for future research or practical applications.

Example: "These findings suggest that targeted therapy could be a promising approach for treating certain types of cancer. Further research is needed to understand the long-term effects and potential side effects of this treatment."

7. Conclude with Key Takeaways

Your conclusion should summarize the main points of your presentation. Restate the importance of your research, highlight the key findings, and suggest possible next steps or future research directions. End with a strong closing statement.

Example: "In conclusion, our study demonstrates the potential of targeted therapy in reducing tumor size. Continued research in this area could lead to more effective cancer treatments and improved patient outcomes."

8. Design Tips for Scientific PowerPoint Presentations

a. Keep it Simple: Avoid cluttered slides. Use a clean, professional design with plenty of white space. Stick to one main idea per slide.

b. Use High-Quality Visuals: Ensure all images, charts, and diagrams are high-resolution and relevant to the content. Poor-quality visuals can distract and detract from your message.

c. Consistent Font and Colors: Use consistent fonts and color schemes throughout your presentation. This creates a cohesive look and helps maintain a professional appearance.

d. Bullet Points and Short Sentences: Use bullet points to break down complex information. Keep sentences short and to the point to enhance readability.

e. Practice Good Typography: Use larger fonts for titles and headings, and ensure body text is legible from a distance. Avoid overly decorative fonts that can be hard to read.

9. Example Slide Deck

Let’s walk through an example slide deck for a scientific presentation on "Innovative Approaches in Cancer Research."

Title Slide:

Title: "Innovative Approaches in Cancer Research"

Subtitle: "A Study on Targeted Therapy"

Presented by: Dr. John Smith, Ph.D.

Affiliation: XYZ Pharmaceutical Company

Outline Slide:

Introduction Slide: "Today, we're exploring innovative approaches in cancer research, focusing on targeted therapy. Cancer remains one of the leading causes of death worldwide, and developing more effective treatments is crucial."

Methodology Slide: "To study the effects of targeted therapy on cancer cells, we conducted a series of experiments using XYZ techniques. This involved cultivating cancer cell lines, applying targeted treatments, and monitoring cell responses over a 12-month period."

Results Slide: "Our results showed a significant reduction in tumor size in mice treated with the new targeted therapy. As illustrated in the graph, the treatment group exhibited a 50% decrease in tumor size compared to the control group."

Discussion Slide: "These findings suggest that targeted therapy could be a promising approach for treating certain types of cancer. Further research is needed to understand the long-term effects and potential side effects of this treatment."

Conclusion Slide: "In conclusion, our study demonstrates the potential of targeted therapy in reducing tumor size. Continued research in this area could lead to more effective cancer treatments and improved patient outcomes."

10. Practice and Feedback

Once your presentation is ready, practice it several times. Rehearse in front of colleagues or friends to get feedback. Pay attention to your pacing, tone, and body language. Make any necessary adjustments based on the feedback you receive.

Work with us

At Ink Narrates, we specialize in creating high-stakes presentations that connect with your audience. Reach out to us through the contact section of our website or schedule a consultation directly from our contact page. We look forward to working with you to bring your scientific findings to life.

Explore our services

Related Posts

How to create the financial projections slide [By experts]

IPO Presentation: How to Nail It and Inspire Investors

Employee Onboarding Presentation: Crafting a Memorable First Day (and Beyond!)

Foundations

Tips on How to Give Better Science Presentations

Scientists wear many hats. They’re researchers, data analysts, and critical thinkers who push boundaries and make new discoveries. One role that scientists often overlook is that of translator. They’re responsible for presenting their ideas to fellow scientists, the media, and interested members of the public.

It’s neglecting this role that often leads to scientific presentations being difficult to understand. We’ve all sat through presentations with illegible text, excessive detail, or a lack of clear structure. Even if you have a brilliant concept, a poorly executed presentation could lead to it being overlooked.

This subject isn’t a new one and it’s one that’s widely discussed within the scientific community. An article in the Society of Behavioral Medicine journal warned in 2021 that “poorly executed science communication hinders science dissemination, implementation, and sustainability.” This article offers practical advice on how to create more engaging, informative presentations that clearly translate your ideas.

Scientific presentations often fail due to data overload, poor design, jargon, and lack of engagement. These issues can obscure research findings and make science inaccessible.

Effective presentations tell a story. They focus on the problem, methods, and key findings, using visuals to highlight data and plain language to explain concepts.

Presentation style matters. Practicing, getting feedback, and using strong opening and closing statements are crucial for capturing the audience’s attention.

Presentations are more than just data. They are opportunities for collaboration, relationship building, and sharing the excitement of scientific discovery.

The Problem with Many Scientific Presentations

Scientific presentations are plagued with many problems. We’ve all sat through presentations and lectures that have felt difficult to understand and stay engaged with.

Common issues with scientific presentations include:

Data overload: Presentations with too much text, complex tables, and small graphs can be difficult to follow and distracting. Microsoft recommends the 6×6 rule . There should be no more than six lines or bullet points on each slide and up to 6 words each.

Poor slide design: While your vocal presentation is important, the slides you show are just as crucial for delivering information. Inconsistent formatting, small font sizes, and unclear visuals can make it difficult to follow a presentation.

Jargon-heavy language: You shouldn’t assume that your audience has the same level of specialized knowledge unless you’re presenting to a group of your peers. Break your presentation down into understandable language that works for your audience.

Monotone delivery: Nothing turns an audience off quicker than a presentation that sounds like it’s being delivered by Siri. Showing a lack of enthusiasm can make even the most exciting research sound uninteresting.

Not addressing the “ So What?”: Don’t get lost in the data. Even engaging presentations can fall flat when they don’t address the wider significance or implication of their research.

Ignoring audience engagement: Scientific presentations can often feel rehearsed or as if the speaker is talking to a wall, instead of an audience. Engaging presentations should have interactive elements, opportunities for questions, and brief pauses.

Consequences of Bad Presentations

A bad presentation doesn’t just show your research in a bad light. It can have wider consequences. A poorly constructed presentation will confuse your audience and make it difficult to understand your research.

Creating engagement and excitement around your research with a successful presentation is key to securing potential collaborations and gaining interest in your work to facilitate future research.

Poor presentations, including relying too heavily on journal articles, can create a negative perception of science and make it inaccessible to the average individual.

7 Tips for Effective Scientific Presentations

You don’t have to reinvent the wheel to deliver an engaging presentation. Preparation is crucial and can help you avoid the common problems discussed above.

Designing an easy-to-follow presentation and curating your language to suit your audience is key to delivering an effective scientific presentation. Here are 7 ways to make your scientific presentations more engaging:

1. Focus on the Story

Every presentation needs a narrative. Before designing your presentation, create an outline that focuses on the problem your research addresses. Address the methods you’ve used and key findings. Identify ways to build a relatable narrative with a logical structure that’s simple to follow.

2. Visual Matter

Your slideshow or PowerPoint acts as the backdrop for your presentation. 65% of people are visual learners. Incorporating clear graphs and diagrams helps your audience interpret information. Use visuals to highlight key data points and short videos to explain more complex processes.

3. Bigger is Generally Better

When you’re designing your presentation, don’t forget that it’ll be shown on a large screen with your audience spread out around the room. Small fonts can be difficult to read, making it harder for audiences to keep up with your presentation. Avoid using text smaller than a size 18-point font and use clean or modern fonts. Arial, Calibri, Helvetica, and Times New Roman are all suitable for scientific presentations.

4. Language is Key

Always consider your audience when choosing the language you use. Define any necessary jargon the first time you use it and stick to plain language wherever possible. You can use analogies and metaphors to help explain complex concepts.

5. Practice and Feedback

Do at least one full rehearsal of your presentation. Time the duration to ensure it’s not unnecessarily long and rehearse in front of colleagues. Take on board constructive feedback and adjust your slides and delivery style accordingly.

6. Strong Start, Memorable Finish

Your presentation needs a hook. Start with a compelling question, a relatable example, or a surprising statistic that instantly grabs the audience’s attention. How you finish your presentation is just as important. Leave your audience wanting more by summarizing your findings, hinting at potential future research, and providing a clear call to action.

7. Signposting

While you might have a script to follow for your presentation, your audience will need signposting to follow it in a logical structure. Use transition phrases like “ this result implies” and “in summary” t o guide your audience through your presentation.

Additional Consideration for Presentations

Context is everything. Your presentation should be crafted with your audience and the wider context in mind.

You wouldn’t present the same information to an audience of undergraduates as a group of C-suite executives. The complexity of the information you present, and how you deliver the information, should be tailored to suit your audience.

Production quality is everything. You don’t have to break the bank to create a sleek, professional-looking presentation that keeps your audience engaged. Software like Canva allows you to present your findings with interactive slides.

Conclusion | Scientific Presentations Aren’t Data Dumps

Approaching scientific presentations as data dumps or just a visual interpretation of your research means your findings can often get lost in translation.

Presentations are an opportunity to nurture collaborations, build relationships, and share the excitement of your work. You can take your career to the next level and further your research by investing time and effort into developing your communication skills.

Use the 7 tips above to improve your scientific presentations and open the doors to new opportunities.

Saleh Ramezani, PhD

Saleh Ramezani is the founder and co-host of Better Science. Saleh believes that science literacy is crucial for navigating today’s science-driven world. Saleh is currently a post-doctoral researcher at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas.

Stay in the loop

Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Related Articles

How to Read a Scientific Paper: A Beginner’s Guide

Predatory Publishers: The Dark Side of Open-Access

Better Science ®

Accessible Knowledge, Infinite Possibilities

Information

Get In Touch

Reference management. Clean and simple.

5 tips for giving a good scientific presentation

What is a scientific presentation?

What is the objective of a scientific presentation, why is giving scientific presentations necessary, how to give a scientific presentation, tip 1: prepare during the days leading up to your talk, tip 2: deal with presentation nerves by practicing simple exercises, tip 3: deliver your talk with intention, tip 4: be adaptable and willing to adjust your presentation, tip 5: conclude your talk and manage questions confidently, concluding thoughts, other sources to help you give a good scientific presentation, frequently asked questions about giving scientific presentations, related articles.

You have made the slides for your scientific presentation. Now, you need to prepare to deliver your talk. But, giving an oral scientific presentation can be nerve-wracking. How do you ensure that you deliver your talk well, and leave a good impression on the audience?

Mastering the skill of giving a good scientific presentation will stand you in good stead for the rest of your career, as it may lead to new collaborations or even new employment opportunities.

In this guide, you’ll find everything you need to know to give a good oral scientific presentation, including

- Why giving scientific presentations is important for your career;

- How to prepare before giving a scientific presentation;

- How to keep the audience engaged and deliver your talk with confidence.

The following tips are a product of our research into the literature on giving scientific presentations as well as our own experiences as scientists in giving and attending talks. We advise on how to make a scientific presentation in another post.

A scientific presentation is a talk or poster where you describe the findings of your research to others. An oral presentation usually involves presenting slides to an audience. You may give an oral scientific presentation at a conference, give an invited seminar at another institution, or give a talk as part of an interview. A PhD thesis defense is one type of scientific presentation.

➡️ Read about how to prepare an excellent thesis defense

The objective of a scientific presentation is to communicate the science such that the audience:

- Learns something new;

- Leaves with a clear understanding of the key message of your research;

- Has confidence in you and your work;

- Remembers you afterward for the right reasons.

As a scientist, one of your responsibilities is disseminating your scientific knowledge by giving presentations. Communicating your research to others is an altruistic act, as it is an opportunity to teach others about your research findings, and the knowledge you have gained while researching your topic.

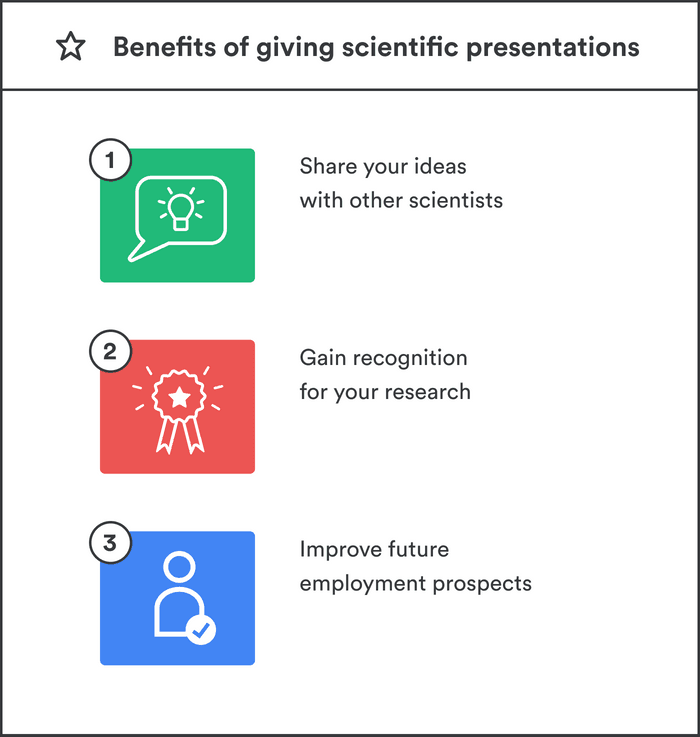

Giving scientific presentations confers many career benefits , such as:

- Having the opportunity to share your ideas and to have insightful conversations with other scientists. For example, a thoughtful question may create a new direction for your research.

- Gaining recognition for your work and generating excitement for your research program can help you to forge new collaborations and to obtain more citations of your papers. It's your chance to impress some of the biggest names in your field, build your reputation as a scientist, and get more people interested in your work.

- Improving your future employment prospects by getting presentation experience in high-stakes settings and by having talks listed on your academic CV.

➡️ Learn how to write an academic CV

You might have just 10 minutes for your talk. But those 10 minutes are your golden ticket. To make them shine, you'll need to put in some homework. You need to think about the story you want to tell , create engaging slides , and practice how you're going to deliver it.

Why all this effort? Because the rewards are potentially huge. Imagine speaking to the top names in your field, boosting your visibility, and getting more eyes on your work. It's more than just a talk; it's your chance to showcase who you are and what you do.

Here we share 5 tips for giving effective scientific presentations.

- Prepare adequately for your talk on the days leading up to it

- Deal with presentation nerves

- Deliver your talk with intention

- Be adaptable

- Conclude your talk with confidence

You should prepare for your talk with the seriousness it deserves and recognize the potential it holds for your career advancement. Here are our suggestions:

- Rehearse your talk multiple times to ensure smooth flow. Know the order of your slides and key transitions without memorizing every word. Practice your speech as though you are discussing with friendly and attentive listeners.

- Record your speech and listen back to yourself giving your talk while doing household chores or while going for a walk. This will help you remember the important points of your talk and feel more comfortable with the flow of it on the day.

- Anticipate potential questions that may arise during your talk, write down your responses to those questions, and practice them aloud.

- Back up your presentation in cloud storage and on a USB key. Bring your laptop with you on the day of your talk, if needed.

- Know the time and location of your talk. Familiarize yourself with the room, if you can. Introduce yourself to the moderator before the session begins.

- Giving a talk is a performance, so preparing yourself physically and mentally is essential. Prioritize good sleep and hydration, and eat healthy, nourishing food on the day of your talk. Plan your attire to be both professional and comfortable.

It’s natural to feel nervous before your talk, but you want to harness that energy to present your work with confidence. Here are some ways to manage your stress levels:

- Remember that your audience want to listen to you and learn from you. Believe that your audience will be kind, friendly, and interested, rather than bored and skeptical.

- Breathing slow and deep before your talk calms the mind and nervous system. Psychologist Amy Cuddy recommends practicing open, confident postures while sitting and standing to help you get into a positive frame of mind.

- Fight off impostor syndrome with positive affirmations. You’ve got this! Remember that you know more about your research than anyone else in the room and you are giving your talk to teach others about it.

Giving your talk with confidence is crucial for your credibility as a scientist. Focusing on your delivery helps ensure that your audience remembers and believes what you say. Here are some techniques to try:

- Before beginning, remember your professional goals and the benefits of giving your presentation. Start with a smile and exhale deeply.

- Memorize a simple opening. After the moderator introduces you, pause and take a breath. Welcome the audience, thank them for coming, and introduce yourself. You don’t need to read the title of your talk. But briefly, say something like, “today I’m going to talk to you about why [topic] is important and [what I hope you will learn from this talk]” in 1-2 sentences. Preparing your opening will settle your nerves and prevent you from starting your talk on a tangential topic, ensuring you stay on time.

- Project confidence outwardly, even if you feel nervous. Stand up tall with your shoulders back and make eye contact with individuals in the audience. Move your focus around the room, so everyone in the audience feels included.

- Maintain open body language and face the audience as much as possible, not your slides.

- Project your voice as much as you can so that people at the back of the room can hear you. Enunciate your words, avoid mumbling, and don’t trail off awkwardly.

- Varying your vocal delivery and intonation will make your talk more interesting and help the audience pay attention, particularly when you want to emphasize key points or transitions.

- Pausing for dramatic effect at crucial moments can help you relax and remember your message, as well as being an effective engagement device.

- A laser pointer can be off-putting for the audience if you are prone to having a shaky hand when nervous. Use a laser pointer only to emphasize information on the slide while providing an explanation. If you design your slides thoughtfully , you won’t need to use a laser pointer.

Not all parts of your talk may go according to plan. Here are some ways to adapt to hitches during your talk:

- Handle talk disruptions gracefully. If you make a mistake, or a technical issue occurs during your talk, remember that it’s okay to skip something and move on without apologizing.

- If you forget to mention something but the audience hasn’t noticed, don’t point it out! They don’t need to know.

- As you give your talk, be time-conscious, and watch the moderator for signals that the time is about to expire. If you realize you won’t have time to discuss all your slides, skip the less important ones. Adjust your presentation on the fly to finish on time, prioritizing content as needed.

- If you run out of time completely, just stop. You don’t have to give a conclusion, but you do need to stop on time! Practicing your talk should prevent this situation.

The ending of your talk is important for emphasizing your key message and ensuring the audience leave with a positive impression of you and your work. Here are some pointers.

- Conclude your talk with a memorized closing statement that summarizes the key take-home message of your research. After making your closing statement, end your talk with a simple “Thank you”. Then pause and wait for the applause. You don’t need to ask if the audience has questions because the moderator will call for questions on your behalf.

- When you receive a question, pause, then repeat the question. This ensures the whole audience understands the question and gives you time to calmly consider your answer.

- In a talk on attaining confidence in your scientific presentations, Michael Alley suggests that if you don’t know the answer to the question, then emphasize what you do know. Say something like, “Although I can’t fully answer your question, I can say [this about the topic].”

- Approach the Q&A with interest rather than anxiety by reframing it as an opportunity to further share your knowledge. Being curious, instead of feeling fearful, can help you shine during what might be the most stressful part of your presentation.

Communicating your research effectively is a key skill for early career scientists to learn. Taking ample time to prepare and practice your presentation is an investment in your scientific development.

But here's the good part: all that effort pays off. Think of your talk as not just a presentation, but as a way to show off what you and your research are all about. Giving a compelling scientific presentation will raise your professional profile as a scientist, lead to more citations of your work, and may even help you obtain a future academic job.

But most importantly of all, giving talks contributes to science, and sharing your knowledge is an act of generosity to the scientific community.

➡️ Questions to ask yourself before you make your talk

➡️ How to give a great scientific talk

1) Have a positive mindset. To help with nerves, breathe deeply and keep in mind that you are an authority on your topic. 2) Be prepared. Have a short list of points for each slide and know the key transition points of your talk. Practice your talk to ensure it flows smoothly. 3) Be well-rested before your talk and eat a light meal on the day of your presentation. A talk is a performance. 4) Project your voice and vary your vocal intonation and pitch to retain the interest of the audience. Take pauses at key moments, for emphasis. 5) Anticipate questions that audience members could ask, and prepare answers for them.

The goal of a scientific presentation is that the audience remembers the key outcomes of your research and that they leave with a good impression of you and your science.

Take a moment to exhale deeply and collect your thoughts after the moderator has introduced you. Don’t read your talk's title. Instead, introduce yourself, thank the audience for attending, and provide a warm welcome. Then say something along the lines of, "Today I'm going to talk to you about why [topic] is important and [what I hope you will learn from this presentation].” A rehearsed opening will ensure that you start your talk on a confident note.

Prepare a memorable closing statement that emphasizes the key message of your talk. Then end with a simple “Thank you”.

Preparation is key. Practice many times to familiarize yourself with the content of your presentation. Before giving your talk, breathe slowly and deeply, and remind yourself that you are the expert on your topic. When giving your talk, stand up tall and use open body language. Remember to project your voice, and make eye contact with members of the audience.

Ten Essentials for Creating a Compelling Scientific PowerPoint Presentation

December 12, 2022

Heming Nelson

We produced our very first webcast over 20 years ago, and no surprise, It was a scientific presentation. Since that time we have recorded or broadcast hundreds of presentations. We've had the opportunity to see some great presentations, and some not-so-great presentations. Below are ten best practices that we’ve identified to elevate your presentation and make sure that your audience remains captivated and interested by your scientific discourse.

1. Start with a Compelling Title Slide The first impression matters. Create a title slide that is visually appealing and clearly conveys the essence of your presentation. Include a concise title, your name, affiliation, and any relevant logos. Keep it clean and professional to set the tone for the rest of your slides.

2. Follow a Consistent Design Theme Consistency is key to a polished presentation. Choose a cohesive design theme that includes a unified color palette and readable fonts (this is worth repeating, don’t use tiny fonts!).

3. Simplify and Clarify Related to the last point, avoid clutter and information overload. Each slide should convey a single idea or concept. Use bullet points, visuals, and concise text to communicate your message effectively. Simplicity not only aids comprehension but also prevents your audience from feeling overwhelmed.

4. Engaging Visuals Over Text Utilize visuals to tell your story. Charts, graphs, images, and diagrams can simplify complex data and enhance understanding. Strive for a balance between visuals and text, with the emphasis on imagery. Visual engagement is crucial for sustaining audience interest.

5. Tell a Story with Structure Organize your presentation in a logical flow. Introduce the problem or context, present your research methods, showcase results, and conclude with impactful insights. A well-structured narrative guides your audience through your scientific journey, making it easier for them to follow and appreciate your work.

6. Font Legibility and Size We are going to repeat this again, but only because it's probably the single biggest problem we see. Opt for legible fonts that are easy to read, even from a distance. Sans-serif fonts like Arial or Calibri are often recommended. Maintain a consistent font size, ensuring that text is large enough for everyone in the audience, including those at the back of the room, to read comfortably.

7. Use Animations Thoughtfully Animations can add a dynamic element to your presentation, but use them judiciously. Avoid excessive transitions and animations that may distract from your message. Employ subtle animations to reveal information gradually, keeping the audience focused on the current point of discussion.

8. Practice Cohesive Branding If applicable, incorporate branding elements from your institution or research project. This adds a professional touch and reinforces your association with reputable entities. Ensure that branding elements complement your overall design theme without overshadowing your content.

9. Check for Consistent Data Formatting If your presentation includes data, ensure consistent formatting across charts and graphs. Use the same scale, color schemes, and legends to maintain visual coherence. Consistent formatting not only improves the aesthetics but also aids in the accurate interpretation of your data.

10. Prepare for Q&A Dedicate a final slide for potential questions from the audience. This shows preparedness and encourages audience interaction. Anticipate possible questions related to your research and be ready to provide concise and informative answers, further enhancing your credibility.

A well-crafted PowerPoint presentation is a powerful tool in the arsenal of a scientist presenting their research. By implementing these ten best practices, you can create a visually compelling and intellectually stimulating presentation that keeps your audience engaged and interested throughout. Remember, the goal is not just to convey information but to foster a connection between your research and your audience, leaving a lasting impression that extends beyond the confines of the presentation room.

For more on the topic, here is a 10-minute video we created for one of our clients that covers much of this material, and more.

Previous post

Tips for Making Video Recordings of Yourself

Why Science Communication is Vital

Have an idea?

Let's Team Up

%20(1).png)

Get in touch

555-555-5555

Limited time offer: 20% off all templates ➞

Scientific Presentation Guide: How to Create an Engaging Research Talk

Creating an effective scientific presentation requires developing clear talking points and slide designs that highlight your most important research results..

Scientific presentations are detailed talks that showcase a research project or analysis results. This comprehensive guide reviews everything you need to know to give an engaging presentation for scientific conferences, lab meetings, and PhD thesis talks. From creating your presentation outline to designing effective slides, the tips in this article will give you the tools you need to impress your scientific peers and superiors.

Step 1. Create a Presentation Outline

The first step to giving a good scientific talk is to create a presentation outline that engages the audience at the start of the talk, highlights only 3-5 main points of your research, and then ends with a clear take-home message. Creating an outline ensures that the overall talk storyline is clear and will save you time when you start to design your slides.

Engage Your Audience

The first part of your presentation outline should contain slide ideas that will gain your audience's attention. Below are a few recommendations for slides that engage your audience at the start of the talk:

- Create a slide that makes connects your data or presentation information to a shared purpose, such as relevance to solving a medical problem or fundamental question in your field of research

- Create slides that ask and invite questions

- Use humor or entertainment

Identify Clear Main Points

After writing down your engagement ideas, the next step is to list the main points that will become the outline slide for your presentation. A great way to accomplish this is to set a timer for five minutes and write down all of the main points and results or your research that you want to discuss in the talk. When the time is up, review the points and select no more than three to five main points that create your talk outline. Limiting the amount of information you share goes a long way in maintaining audience engagement and understanding.

Create a Take-Home Message

And finally, you should brainstorm a single take-home message that makes the most important main point stand out. This is the one idea that you want people to remember or to take action on after your talk. This can be your core research discovery or the next steps that will move the project forward.

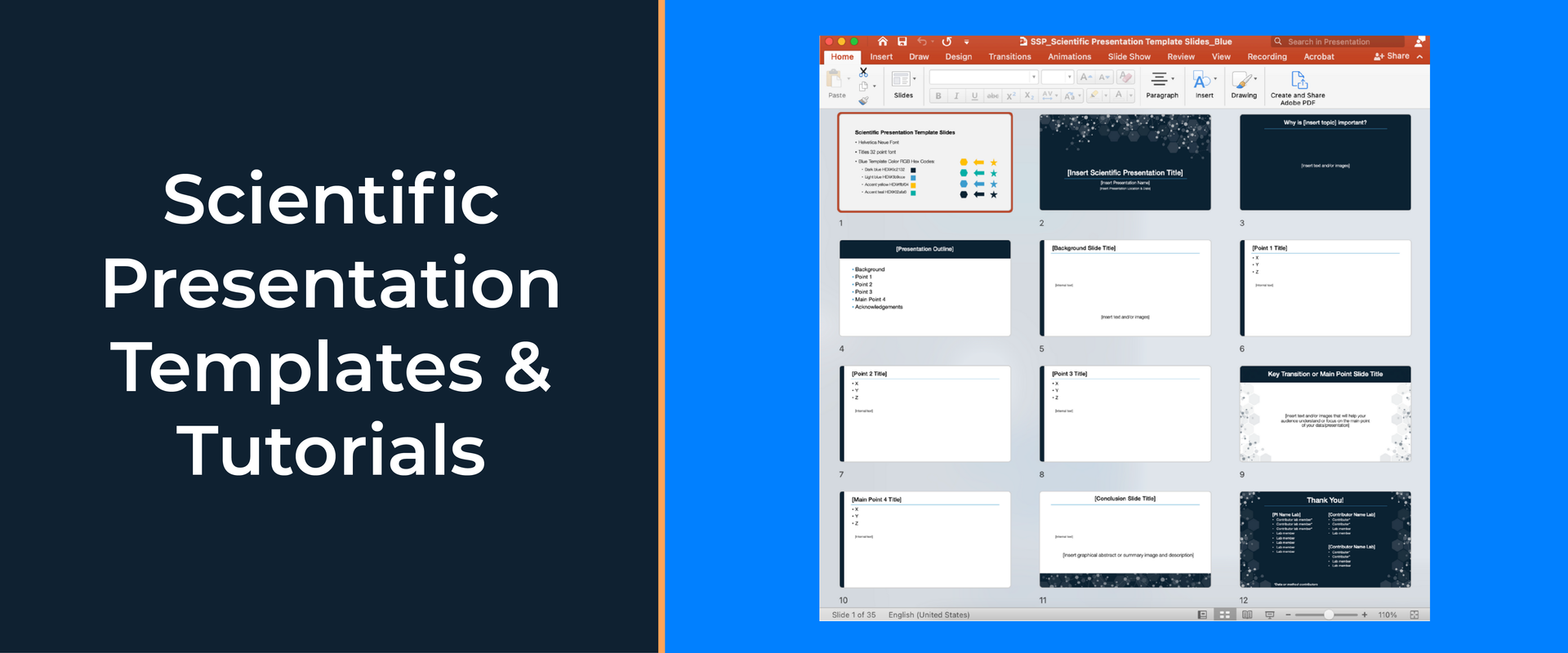

Step 2. Choose a Professional Slide Theme

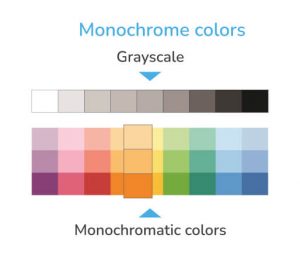

After you have a good presentation outline, the next step is to choose your slide colors and create a theme. Good slide themes use between two to four main colors that are accessible to people with color vision deficiencies. Read this article to learn more about choosing the best scientific color palettes .

You can also choose templates that already have an accessible color scheme. However, be aware that many PowerPoint templates that are available online are too cheesy for a scientific audience. Below options to download professional scientific slide templates that are designed specifically for academic conferences, research talks, and graduate thesis defenses.

Step 3. Design Your Slides

Designing good slides is essential to maintaining audience interest during your scientific talk. Follow these four best practices for designing your slides:

- Keep it simple: limit the amount of information you show on each slide

- Use images and illustrations that clearly show the main points with very little text.

- Read this article to see research slide example designs for inspiration

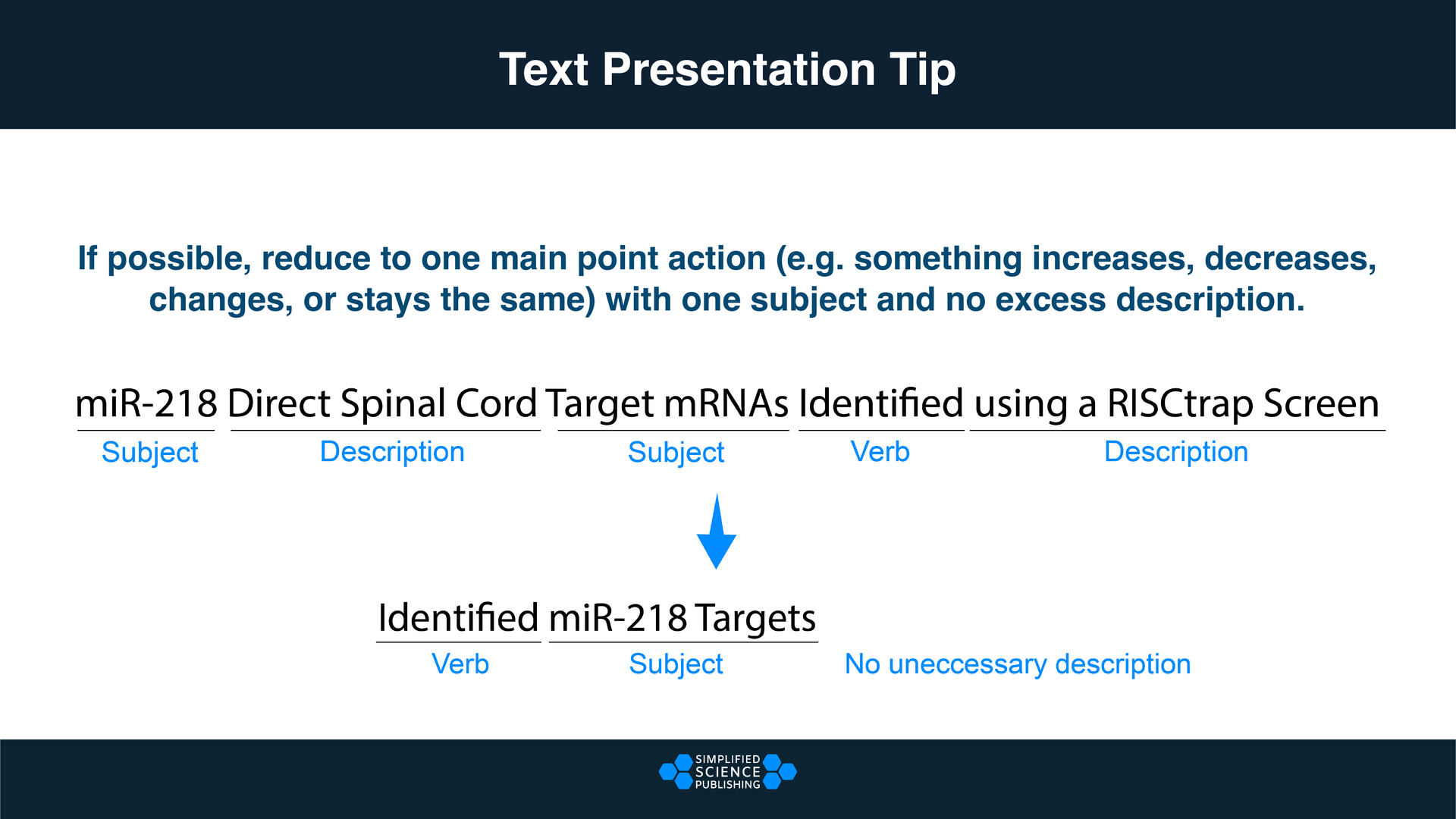

- When you are using text, try to reduce the scientific jargon that is unnecessary. Text on research talk slides needs to be much more simple than the text used in scientific publications (see example below).

- Use appear/disappear animations to break up the details into smaller digestible bites

- Sign up for the free presentation design course to learn PowerPoint animation tricks

Scientific Presentation Design Summary

All of the examples and tips described in this article will help you create impressive scientific presentations. Below is the summary of how to give an engaging talk that will earn respect from your scientific community.

Step 1. Draft Presentation Outline. Create a presentation outline that clearly highlights the main point of your research. Make sure to start your talk outline with ideas to engage your audience and end your talk with a clear take-home message.

Step 2. Choose Slide Theme. Use a slide template or theme that looks professional, best represents your data, and matches your audience's expectations. Do not use slides that are too plain or too cheesy.

Step 3. Design Engaging Slides. Effective presentation slide designs use clear data visualizations and limits the amount of information that is added to each slide.

And a final tip is to practice your presentation so that you can refine your talking points. This way you will also know how long it will take you to cover the most essential information on your slides. Thank you for choosing Simplified Science Publishing as your science communication resource and good luck with your presentations!

Interested in free design templates and training?

Explore scientific illustration templates and courses by creating a Simplified Science Publishing Log In. Whether you are new to data visualization design or have some experience, these resources will improve your ability to use both basic and advanced design tools.

Interested in reading more articles on scientific design? Learn more below:

Data Storytelling Techniques: How to Tell a Great Data Story in 4 Steps

Best Science PowerPoint Templates and Slide Design Examples

Content is protected by Copyright license. Website visitors are welcome to share images and articles, however they must include the Simplified Science Publishing URL source link when shared. Thank you!

Online Courses

Stay up-to-date for new simplified science courses, subscribe to our newsletter.

Thank you for signing up!

You have been added to the emailing list and will only recieve updates when there are new courses or templates added to the website.

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience and we do not sell data. By using this website, you are giving your consent for us to set cookies: View Privacy Policy

Simplified Science Publishing, LLC

Loading metrics

Open Access

Ten simple rules for effective presentation slides

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Biomedical Engineering and the Center for Public Health Genomics, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, United States of America

- Kristen M. Naegle

Published: December 2, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554

- Reader Comments

Citation: Naegle KM (2021) Ten simple rules for effective presentation slides. PLoS Comput Biol 17(12): e1009554. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554

Copyright: © 2021 Kristen M. Naegle. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The author received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The author has declared no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The “presentation slide” is the building block of all academic presentations, whether they are journal clubs, thesis committee meetings, short conference talks, or hour-long seminars. A slide is a single page projected on a screen, usually built on the premise of a title, body, and figures or tables and includes both what is shown and what is spoken about that slide. Multiple slides are strung together to tell the larger story of the presentation. While there have been excellent 10 simple rules on giving entire presentations [ 1 , 2 ], there was an absence in the fine details of how to design a slide for optimal effect—such as the design elements that allow slides to convey meaningful information, to keep the audience engaged and informed, and to deliver the information intended and in the time frame allowed. As all research presentations seek to teach, effective slide design borrows from the same principles as effective teaching, including the consideration of cognitive processing your audience is relying on to organize, process, and retain information. This is written for anyone who needs to prepare slides from any length scale and for most purposes of conveying research to broad audiences. The rules are broken into 3 primary areas. Rules 1 to 5 are about optimizing the scope of each slide. Rules 6 to 8 are about principles around designing elements of the slide. Rules 9 to 10 are about preparing for your presentation, with the slides as the central focus of that preparation.

Rule 1: Include only one idea per slide

Each slide should have one central objective to deliver—the main idea or question [ 3 – 5 ]. Often, this means breaking complex ideas down into manageable pieces (see Fig 1 , where “background” information has been split into 2 key concepts). In another example, if you are presenting a complex computational approach in a large flow diagram, introduce it in smaller units, building it up until you finish with the entire diagram. The progressive buildup of complex information means that audiences are prepared to understand the whole picture, once you have dedicated time to each of the parts. You can accomplish the buildup of components in several ways—for example, using presentation software to cover/uncover information. Personally, I choose to create separate slides for each piece of information content I introduce—where the final slide has the entire diagram, and I use cropping or a cover on duplicated slides that come before to hide what I’m not yet ready to include. I use this method in order to ensure that each slide in my deck truly presents one specific idea (the new content) and the amount of the new information on that slide can be described in 1 minute (Rule 2), but it comes with the trade-off—a change to the format of one of the slides in the series often means changes to all slides.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Top left: A background slide that describes the background material on a project from my lab. The slide was created using a PowerPoint Design Template, which had to be modified to increase default text sizes for this figure (i.e., the default text sizes are even worse than shown here). Bottom row: The 2 new slides that break up the content into 2 explicit ideas about the background, using a central graphic. In the first slide, the graphic is an explicit example of the SH2 domain of PI3-kinase interacting with a phosphorylation site (Y754) on the PDGFR to describe the important details of what an SH2 domain and phosphotyrosine ligand are and how they interact. I use that same graphic in the second slide to generalize all binding events and include redundant text to drive home the central message (a lot of possible interactions might occur in the human proteome, more than we can currently measure). Top right highlights which rules were used to move from the original slide to the new slide. Specific changes as highlighted by Rule 7 include increasing contrast by changing the background color, increasing font size, changing to sans serif fonts, and removing all capital text and underlining (using bold to draw attention). PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554.g001

Rule 2: Spend only 1 minute per slide

When you present your slide in the talk, it should take 1 minute or less to discuss. This rule is really helpful for planning purposes—a 20-minute presentation should have somewhere around 20 slides. Also, frequently giving your audience new information to feast on helps keep them engaged. During practice, if you find yourself spending more than a minute on a slide, there’s too much for that one slide—it’s time to break up the content into multiple slides or even remove information that is not wholly central to the story you are trying to tell. Reduce, reduce, reduce, until you get to a single message, clearly described, which takes less than 1 minute to present.

Rule 3: Make use of your heading

When each slide conveys only one message, use the heading of that slide to write exactly the message you are trying to deliver. Instead of titling the slide “Results,” try “CTNND1 is central to metastasis” or “False-positive rates are highly sample specific.” Use this landmark signpost to ensure that all the content on that slide is related exactly to the heading and only the heading. Think of the slide heading as the introductory or concluding sentence of a paragraph and the slide content the rest of the paragraph that supports the main point of the paragraph. An audience member should be able to follow along with you in the “paragraph” and come to the same conclusion sentence as your header at the end of the slide.

Rule 4: Include only essential points

While you are speaking, audience members’ eyes and minds will be wandering over your slide. If you have a comment, detail, or figure on a slide, have a plan to explicitly identify and talk about it. If you don’t think it’s important enough to spend time on, then don’t have it on your slide. This is especially important when faculty are present. I often tell students that thesis committee members are like cats: If you put a shiny bauble in front of them, they’ll go after it. Be sure to only put the shiny baubles on slides that you want them to focus on. Putting together a thesis meeting for only faculty is really an exercise in herding cats (if you have cats, you know this is no easy feat). Clear and concise slide design will go a long way in helping you corral those easily distracted faculty members.

Rule 5: Give credit, where credit is due

An exception to Rule 4 is to include proper citations or references to work on your slide. When adding citations, names of other researchers, or other types of credit, use a consistent style and method for adding this information to your slides. Your audience will then be able to easily partition this information from the other content. A common mistake people make is to think “I’ll add that reference later,” but I highly recommend you put the proper reference on the slide at the time you make it, before you forget where it came from. Finally, in certain kinds of presentations, credits can make it clear who did the work. For the faculty members heading labs, it is an effective way to connect your audience with the personnel in the lab who did the work, which is a great career booster for that person. For graduate students, it is an effective way to delineate your contribution to the work, especially in meetings where the goal is to establish your credentials for meeting the rigors of a PhD checkpoint.

Rule 6: Use graphics effectively

As a rule, you should almost never have slides that only contain text. Build your slides around good visualizations. It is a visual presentation after all, and as they say, a picture is worth a thousand words. However, on the flip side, don’t muddy the point of the slide by putting too many complex graphics on a single slide. A multipanel figure that you might include in a manuscript should often be broken into 1 panel per slide (see Rule 1 ). One way to ensure that you use the graphics effectively is to make a point to introduce the figure and its elements to the audience verbally, especially for data figures. For example, you might say the following: “This graph here shows the measured false-positive rate for an experiment and each point is a replicate of the experiment, the graph demonstrates …” If you have put too much on one slide to present in 1 minute (see Rule 2 ), then the complexity or number of the visualizations is too much for just one slide.

Rule 7: Design to avoid cognitive overload

The type of slide elements, the number of them, and how you present them all impact the ability for the audience to intake, organize, and remember the content. For example, a frequent mistake in slide design is to include full sentences, but reading and verbal processing use the same cognitive channels—therefore, an audience member can either read the slide, listen to you, or do some part of both (each poorly), as a result of cognitive overload [ 4 ]. The visual channel is separate, allowing images/videos to be processed with auditory information without cognitive overload [ 6 ] (Rule 6). As presentations are an exercise in listening, and not reading, do what you can to optimize the ability of the audience to listen. Use words sparingly as “guide posts” to you and the audience about major points of the slide. In fact, you can add short text fragments, redundant with the verbal component of the presentation, which has been shown to improve retention [ 7 ] (see Fig 1 for an example of redundant text that avoids cognitive overload). Be careful in the selection of a slide template to minimize accidentally adding elements that the audience must process, but are unimportant. David JP Phillips argues (and effectively demonstrates in his TEDx talk [ 5 ]) that the human brain can easily interpret 6 elements and more than that requires a 500% increase in human cognition load—so keep the total number of elements on the slide to 6 or less. Finally, in addition to the use of short text, white space, and the effective use of graphics/images, you can improve ease of cognitive processing further by considering color choices and font type and size. Here are a few suggestions for improving the experience for your audience, highlighting the importance of these elements for some specific groups:

- Use high contrast colors and simple backgrounds with low to no color—for persons with dyslexia or visual impairment.

- Use sans serif fonts and large font sizes (including figure legends), avoid italics, underlining (use bold font instead for emphasis), and all capital letters—for persons with dyslexia or visual impairment [ 8 ].

- Use color combinations and palettes that can be understood by those with different forms of color blindness [ 9 ]. There are excellent tools available to identify colors to use and ways to simulate your presentation or figures as they might be seen by a person with color blindness (easily found by a web search).

- In this increasing world of virtual presentation tools, consider practicing your talk with a closed captioning system capture your words. Use this to identify how to improve your speaking pace, volume, and annunciation to improve understanding by all members of your audience, but especially those with a hearing impairment.

Rule 8: Design the slide so that a distracted person gets the main takeaway