- The Journal

- Vol. 16, No. 2

How Family Background Influences Student Achievement

Anna J. Egalite

This article is part of a new Education Next series commemorating the 50th anniversary of James S. Coleman’s groundbreaking report , “Equality of Educational Opportunity.” The full series will appear in the Spring 2016 issue of Education Next .

To the dismay of federal officials, the Coleman Report had concluded that “schools are remarkably similar in the effect they have on the achievement of their pupils when the socio-economic background of the students is taken into account.” Or, as one sociologist supposedly put it to the scholar-politician Daniel Patrick Moynihan, “Have you heard what Coleman is finding? It’s all family.”

The Coleman Report’s conclusions concerning the influences of home and family were at odds with the paradigm of the day. The politically inconvenient conclusion that family background explained more about a child’s achievement than did school resources ran contrary to contemporary priorities, which were focused on improving educational inputs such as school expenditure levels, class size, and teacher quality. Indeed, less than a year before the Coleman Report’s release, President Lyndon Johnson had signed the Elementary and Secondary Education Act into law, dedicating federal funds to disadvantaged students through a Title 1 program that still remains the single largest investment in K–12 education, currently reaching approximately 21 million students at an annual cost of about $14.4 billion.

So what exactly had Coleman uncovered? Differences among schools in their facilities and staffing “are so little related to achievement levels of students that, with few exceptions, their effect fails to appear even in a survey of this magnitude,” the authors concluded.

Zeroing In on Family Background

Coleman’s advisory panel refused to sign off on the report, citing “methodological concerns” that continue to reverberate. Subsequent research has corroborated the finding that family background is strongly correlated with student performance in school. A correlation between family background and educational and economic success, however, does not tell us whether the relationship between the two is independent of any school impacts. The associations between home life and school performance that Coleman documented may actually be driven by disparities in school or neighborhood quality rather than family influences. Often, families choose their children’s schools by selecting their community or neighborhood, and children whose parents select good schools may benefit as a consequence. In the elusive quest to uncover the determinants of students’ academic success, therefore, it is important to rely on experimental or quasi-experimental research that identifies effects of family background that operate separately and apart from any school effects.

In this essay I look at four family variables that may influence student achievement: family education, family income, parents’ criminal activity, and family structure. I then consider the ways in which schools can offset the effects of these factors.

Parental Education. Better-educated parents are more likely to consider the quality of the local schools when selecting a neighborhood in which to live. Once their children enter a school, educated parents are also more likely to pay attention to the quality of their children’s teachers and may attempt to ensure that their children are adequately served. By participating in parent-teacher conferences and volunteering at school, they may encourage staff to attend to their children’s individual needs.

In addition, highly educated parents are more likely than their less-educated counterparts to read to their children. Educated parents enhance their children’s development and human capital by drawing on their own advanced language skills in communicating with their children. They are more likely to pose questions instead of directives and employ a broader and more complex vocabulary. Estimates suggest that, by age 3, children whose parents receive public assistance hear less than a third of the words encountered by their higher-income peers. As a result, the children of highly educated parents are capable of more complex speech and have more extensive vocabularies before they even start school.

Highly educated parents can also use their social capital to promote their children’s development. A cohesive social network of well-educated individuals socializes children to expect that they too will attain high levels of academic success. It can also transmit cultural capital by teaching children the specific behaviors, patterns of speech, and cultural references that are valued by the educational and professional elite.

In most studies, parental education has been identified as the single strongest correlate of children’s success in school, the number of years they attend school, and their success later in life. Because parental education influences children’s learning both directly and through the choice of a school, we do not know how much of the correlation can be attributed to direct impact and how much to school-related factors. Teasing out the distinct causal impact of parental education is tricky, but given the strong association between parental education and student achievement in every industrialized society, the direct impact is undoubtedly substantial. Furthermore, quasi-experimental strategies have found positive effects of parental education on children’s outcomes. For instance, one study of Korean children adopted into American families shows that the adoptive mother’s education level is significantly associated with the child’s educational attainment.

Family Income. As with parental education, family income may have a direct impact on a child’s academic outcomes, or variations in achievement could simply be a function of the school the child attends: parents with greater financial resources can identify communities with higher-quality schools and choose more-expensive neighborhoods—the very places where good schools are likely to be. More-affluent parents can also use their resources to ensure that their children have access to a full range of extracurricular activities at school and in the community.

But it’s not hard to imagine direct effects of income on student achievement. Parents who are struggling economically simply don’t have the time or the wherewithal to check homework, drive children to summer camp, organize museum trips, or help their kids plan for college. Working multiple jobs or inconvenient shifts makes it hard to dedicate time for family dinners, enforce a consistent bedtime, read to infants and toddlers, or invest in music lessons or sports clubs. Even small differences in access to the activities and experiences that are known to promote brain development can accumulate, resulting in a sizable gap between two groups of children defined by family circumstances.

It is challenging to find rigorous experimental or quasi-experimental evidence to disentangle the direct effects of home life from the effects of the school a family selects. While Coleman claimed that family and peers had an effect on student achievement that was distinct from the influence of schools or neighborhoods, his research design was inadequate to support this conclusion. All he was able to show was that family characteristics had a strong correlation with student achievement.

Separating out the independent effects of family education and family income is also difficult. We do not know if low income and financial instability alone can adversely affect children’s behavior, emotional stability, and educational outcomes. Evidence from the negative-income-tax experiments carried out by the federal government between 1968 and 1982 showed only mixed effects of income on children’s outcomes, and subsequent work by the University of Chicago’s Susan Mayer cast doubt on any causal relationship between parental income and child well-being. However, a recent study by Gordon Dahl and Lance Lochner, exploiting quasi-experimental variation in the Earned Income Tax Credit, provides convincing evidence that increases in family income can lift the achievement levels of students raised in low-income working families, even holding other factors constant.

Parental Incarceration. The Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that 2.3 percent of U.S. children have a parent in federal or state prison. Black children are 7.5 times more likely and Hispanic children 2.5 times more likely than white children to have an incarcerated parent. Incarceration removes a wage earner from the home, lowering household income. One estimate suggests that two-thirds of incarcerated fathers had provided the primary source of family income before their imprisonment. As a result, children with a parent in prison are at greater risk of homelessness, which in turn can have grave consequences: the receipt of social and medical services and assignment to a traditional public school all require a stable home address. The emotional strain of a parent’s incarceration can also take its toll on a child’s achievement in school.

Quantifying the causal effects of parental incarceration has proven challenging, however. While correlational research finds that the odds of finishing high school are 50 percent lower for children with an incarcerated parent, parents who are in prison may have less education, lower income, more limited access to quality schools, and other attributes that adversely affect their children’s success in school. A recent review of 22 studies of the effect of parental incarceration on child well-being concludes that, to date, no research in this area has been able to leverage a natural experiment to produce quasi-experimental estimates. Just how large a causal impact parental incarceration has on children remains an important but largely uncharted topic for future research.

Family Structure. While most American children still live with both of their biological or adoptive parents, family structures have become more diverse in recent years, and living arrangements have grown increasingly complex. In particular, the two-parent family is vanishing among the poor.

Recent research by MIT economist David Autor and colleagues generates quasi-experimental estimates of family background by simultaneously accounting for the impact of neighborhood environment and school quality to investigate why boys fare worse than girls in disadvantaged families. Comparing boys to their sisters in a data set that includes more than 1 million children born in Florida between 1992 and 2002, the authors demonstrate a persistent gender gap in graduation and truancy rates, incidence of behavioral and cognitive disabilities, and standardized test scores.

Policies to Counter Family Disadvantage

Policymakers who are weighing competing approaches to countering the influence of family disadvantage face a tough choice: Should they try to improve schools (to overcome the effects of family background) or directly address the effects of family background?

The question is critical. If family background is decisive regardless of the quality of the school, then the road to equal opportunity will be long and hard. Increasing the level of parental education is a multigenerational challenge, while reducing the rising disparities in family income would require massive changes in public policy, and reversing the growth in the prevalence of single-parent families would also prove challenging. And, while efforts to reduce incarceration rates are afoot, U.S. crime rates remain among the highest in the world. Given these obstacles, if schools themselves can offset differences in family background, the chances of achieving a more egalitarian society greatly improve.

For these reasons, scholars need to continue to tackle the causality question raised by Coleman’s pathbreaking study. Although the obstacles to causal inference are steep, education researchers should focus on quasi-experimental approaches relying on sibling comparisons, changes in state laws over time, or policy quirks—such as policy implementation timelines that vary across municipalities—that facilitate research opportunities.

Given what is currently known, a holistic approach that simultaneously attempts to strengthen both home and school influences in disadvantaged communities is worthy of further exploration. A number of contemporary and past initiatives point to the potential of this comprehensive approach.

Promise Neighborhoods

“Promise Neighborhoods,” which are funded by a grant program of the U.S. Department of Education, serve distressed communities by delivering a continuum of services through multiple government agencies, nonprofit organizations, churches, and agencies of civil society. These neighborhood initiatives use “wraparound” programs that take a holistic approach to improving the educational achievement of low-income students. The template for the approach is the Harlem Children’s Zone (HCZ), a 97-block neighborhood in New York City that combines charter schooling with a full package of social, medical, and community support services. The programs and resources are available to the families at no cost.

Services available in the HCZ include a Baby College, where expectant parents can learn about child development and gain parenting skills; two charter schools and a college success office, which provides individualized counseling and guidance to graduates on university campuses across the country; free legal services, tax preparation, and financial counseling; employment workshops and job fairs; a 50,000-square-foot facility that offers recreational and nutrition classes; and a food services team that provides breakfast, lunch, and a snack every school day to more than 2,000 students.

Research by Will Dobbie and Roland Fryer demonstrates that the impact of attending an HCZ charter middle school on students’ test scores is comparable to the impressive effects seen at high-performing charter schools such as the Knowledge Is Power Program (known as KIPP schools). Students who win admission by lottery and attend an HCZ school also have higher on-time graduation rates than their peers and are less likely to become teen parents or land in prison. Although some community services are available to HCZ residents only, results show that students who live outside the HCZ experience similar benefits simply from attending the Promise Academy. That is, Dobbie and Fryer do not find any additional benefits associated with the resident-only supplementary services that distinguish the Promise Neighborhoods approach. (In many instances, the mean scores for children who live within the zone are higher than those for nonresidents, but these differences are not statistically significant.)

There are two caveats to keep in mind in regard to this finding that support the case for continued experimentation with and evaluation of Promise Neighborhoods. First, many of the wraparound services offered in the HCZ are provided through the school and are thus available to HCZ residents and nonresidents alike. For instance, all Promise Academy students receive free nutritious meals; medical, dental, and mental health services; and food baskets for their parents. The services that nonresidents cannot access are things such as tax preparation and financial advising, parenting classes through the Baby College, and job fairs. It may be that both groups of students are accessing the most beneficial supplementary services.

The second caveat is that the HCZ is a “pipeline” model that aims to transform an entire community by targeting services across many different domains. Therefore, we may have to wait until a cohort of students has progressed through that pipeline before we can get a full picture of how these comprehensive services have benefited them. The first cohort to complete the entire HCZ program is expected to graduate from high school in 2020.

The main drawback of the Promise Neighborhoods model is its high cost. To cover the expenses of running the Promise Academy Charter School and the afterschool and wraparound programs, the HCZ spends about $19,272 per pupil. While this price tag is about $3,100 higher than the median per-pupil cost in New York State, it is still about $14,000 lower than what is spent by a district at the 95th percentile. If future research can demonstrate that the HCZ positively influences longer-term outcomes such as college graduation rates, income, and mortality, the model will hold tremendous potential that may well justify its costs.

Early Childhood Education

Early childhood programs can provide a source of enrichment for needy children, ensuring them a solid start in a world where those with inadequate education are increasingly marginalized. Neuroscientists estimate that about 90 percent of the brain develops between birth and age 5, supporting the case for expanded access to early childhood programs. While the United States spends abundantly on elementary and secondary schoolchildren ($12,401 per student per year in 2013–14 dollars), it devotes dramatically less than other wealthy countries to children in their first few years of life.

Four years before James Coleman released his report, a group of underprivileged, at-risk toddlers at the Perry Preschool in Ypsilanti, Michigan, were randomly selected for a preschool intervention that consisted of daily coaching from highly trained teachers as well as visits to their homes. After just one year, those in the experimental treatment group were registering IQ scores 10 points higher than their peers in the control group. The test-score effects had disappeared by age 10, but follow-up analyses of the Perry Preschool treatment group revealed impressive longer-term outcomes that included a significant increase in their high-school graduation rate and the probability of earning at least $20,000 a year as adults, as well as a 19 percent decrease in their probability of being arrested five or more times. Similar small-scale, “hothouse” preschool experiments in Chicago, upstate New York, and North Carolina have all shown comparable benefits.

Unfortunately, attempts to scale up such programs have proved challenging. Studies of the Head Start program, for instance, have uncovered mixed evidence of its effectiveness. Modest impacts on students’ cognitive skills mostly fade out by the end of 1st grade. Such results have led many to question whether quality can be consistently maintained when a program such as Head Start is implemented broadly. Indeed, recent research has revealed considerable differences in Head Start’s effectiveness from site to site. Variation in inputs and practices among Head Start centers explains about a third of these differences, a finding that may offer clues as to the contextual factors that influence the program’s varying levels of success.

Although the policymaker’s challenge is to figure out how to expand access to such programs while preserving quality, evidence suggests that investment in early childhood education has the potential to significantly address disparities that arise from family disadvantage.

Small Schools of Choice

Traditional public schools assign a child to a given school based exclusively on his family’s place of residence. As Coleman pointed out, residential assignment promotes stratification between schools by family background, because it creates incentives for families of means to move to the “good” school districts. Under this system, schools cannot serve as the equal-opportunity engines of our society. Instead, residential assignment often replicates within the school system the same family advantages and disadvantages that exist in the community.

The most promising social policy for combating the effects of family background, then, could well be the expansion of programs that allow families to choose schools without regard to their neighborhood of residence. An analysis of more than 100 small schools of choice in New York City between 2002 and 2008 revealed a 9.5 percent increase in the graduation rate of a group of educationally and economically disadvantaged students, at no extra cost to the city. Positive results have also been observed with respect to student test scores for charter schools in New York City, Boston, Los Angeles, and New Orleans.

Small schools of choice might also build the social capital that Coleman considered crucial for student success. First, small schools are well positioned to build a strong sense of community through the development of robust student-teacher, parent-teacher, and student-student relationships. Helping students to cultivate dense networks of social relationships better equips them to handle life’s challenges and is particularly vital given the disintegration of many social structures today. While schools may not be able to compensate fully for the disruptive effects of a dysfunctional or unstable family, a robust school culture can transform the “social ecology” of a disadvantaged child.

A small school of choice also engenders a voluntary community that comes together over strong ties and shared values. Typically, schools of choice feature a clearly defined mission and set of core values, which may derive from religious traditions and beliefs. The Notre Dame ACE Academy schools, for instance, strive for the twin goals of preparing students for college and for heaven. By explicitly defining their mission, schools can appeal to families who share their values and are eager to contribute to the growth of the community. A focused mission also helps school administrators attract like-minded teachers and thus promotes staff collegiality. A warm and cohesive teaching staff can be particularly beneficial for children from unstable homes, whose parents may not regularly express emotional closeness or who fail to communicate effectively. Exposure to well-functioning adult role models at school might compensate for such deficits, promoting well-being and positive emotional development.

Implications for Policy

Determining the causal relationships between family background and child well-being has posed a daunting challenge. Family characteristics are often tightly correlated with features of the neighborhood environment, making it difficult to determine the independent influences of each. But getting a solid understanding of causality is critical to the debate over whether to intervene inside or outside of school.

The results of quasi-experimental research, as well as common sense, tell us that children who grow up in stable, well-resourced families have significant advantages over their peers who do not—including access to better schools and other educational services. Policies that place schools at center stage have the potential to disrupt the cycle of economic disadvantage to ensure that children born into poverty aren’t excluded from the American dream.

In opening our eyes to the role of family background in the creation of inequality, Coleman wasn’t suggesting that we shrug our shoulders and learn to live with it. But in attacking the achievement gap, as his research would imply, we need to mobilize not only our schools but also other institutions. Promise Neighborhoods offer cradle-to-career supports to help children successfully navigate the challenges of growing up. Early childhood programs provide intervention at a critical time, when children’s brains take huge leaps in development. Finally, small schools of choice can help to build a strong sense of community, which could particularly benefit inner-city neighborhoods where traditional institutions have been disintegrating.

Schools alone can’t level the vast inequalities that students bring to the schoolhouse door, but a combination of school programs, social services, community organizations, and civil society could make a major difference. Ensuring that all kids, regardless of family background, have a decent chance of doing better than their parents is an important societal and policy goal. Innovative approaches such as those outlined here could help us achieve it.

Anna J. Egalite is an assistant professor in the Department of Educational Leadership, Policy, and Human Development at the College of Education, North Carolina State University.

For more, please see “ The Top 20 Education Next Articles of 2023 .”

This article appeared in the Spring 2016 issue of Education Next . Suggested citation format:

Egalite, A.J. (2016). How Family Background Influences Student Achievement: Can schools narrow the gap? Education Next , 16(2), 70-78.

Last Updated

License this Content

Latest Issue

Vol. 24, No. 4

Calculate for all schools

Your chance of acceptance, your chancing factors, extracurriculars, personal background essay examples.

Hey everyone! I'm working on my college applications, and part of it requires a personal background essay. I'm a little stuck, so if you guys could share some examples or tips, that'd be great! Please help me out, thanks!

Hello! It's understandable that writing a personal background essay can be challenging. Here are some tips to get you started and an example of how you might approach this essay:

1. Reflect on what makes your background unique. Consider your family's history, culture, traditions, values, and how these have shaped your experiences.

2. Delve into the details. Discuss specific experiences, anecdotes, or events that have had a significant impact on your life and highlight the lessons you've gained from your background.

3. Be authentic. Write from the heart and let your personality shine through. This essay is your opportunity to help the admissions officers get to know you beyond your stats and accomplishments.

4. Avoid clichés. Personal background essays are quite common, so if you're writing about a widely-covered topic (moving, learning a new language, etc.), try to find a unique angle or aspect that will set your essay apart.

Growing up in a multigenerational household, I've had the rare privilege of experiencing diverse perspectives on life from my grandparents, parents, and siblings. My grandparents, who emigrated from Vietnam, taught me the importance of staying true to our cultural heritage and maintaining strong connections with family. Daily rituals like preparing and enjoying traditional Vietnamese meals, participating in Lunar New Year celebrations, and listening to stories about my grandparents' journey to the United States helped me appreciate the strength and resilience of my ancestors.

However, this cultural pride was not always something I cherished. As a child, I was bullied for my Banh Khot and Banh Mi lunches, and I'd often ask my parents to pack more generic-looking sandwiches to avoid feeling like an outsider at school. It wasn't until my grandmother shared her own story of assimilation and how she strived to maintain her cultural identity in a new country that I realized the value of embracing my heritage. Inspired by her courage, I decided to educate my peers about Vietnamese traditions and founded a cultural exchange club at school. Together, we explored our heritages, organizing potlucks, cultural presentations, and language exchange sessions.

Through this experience, I've learned that embracing who I am and the unique background I come from has made me a stronger person. My personal background has taught me to be open to learning about other cultures, which I look forward to bringing to my future college community.

About CollegeVine’s Expert FAQ

CollegeVine’s Q&A seeks to offer informed perspectives on commonly asked admissions questions. Every answer is refined and validated by our team of admissions experts to ensure it resonates with trusted knowledge in the field.

Genius High

Impact of Family Background on Educational Achievement

To what extent does family background influence educational achievement.

**Introduction** Educational achievement is a complex and multifaceted outcome that is influenced by a myriad of factors, with family background being a significant determinant. In this essay, we will explore the extent to which family background influences educational achievement, considering various factors such as ethnicity, social class, cultural influences, and other relevant aspects. We will examine both the supportive arguments for the influence of family background on educational achievement as well as the opposing viewpoints that suggest other factors such as peer groups and school policies may be more influential. **Factors Influencing Educational Achievement** *Material Factors*: It is widely acknowledged that children from disadvantaged backgrounds, such as those living in poverty, face numerous challenges that can impede their educational success. Issues such as overcrowded living conditions, the necessity of part-time jobs to support the family, and limited access to educational resources at home can all negatively impact a student's academic performance. *Cultural Factors*: Family background can also play a role in shaping attitudes towards education. Working-class parents, for example, may prioritize immediate financial stability over long-term educational attainment, leading to a devaluation of academic achievement within the household. Moreover, a lack of successful role models within the family who have pursued higher education can limit a child's aspirations and motivation. *Role Models and Cultural Capital*: Sociologist Pierre Bourdieu's concept of cultural capital highlights how familiarity with intellectual pursuits, exposure to cultural activities, and knowledge of the education system can confer advantages to some students. Families with higher cultural capital are better equipped to support their children's educational endeavors, leading to differential educational outcomes based on family background. *Gender Roles*: Traditional gender roles can also influence educational achievement, with girls sometimes being discouraged from pursuing academic success due to societal expectations related to marriage and family responsibilities. Conversely, boys may face pressures to conform to masculine norms that prioritize other forms of success over academic achievement. *Language and Minority Students*: For minority students, language barriers and cultural differences can pose significant challenges to educational achievement. Students who are not taught in their home language may struggle to comprehend coursework and effectively communicate their knowledge, resulting in academic underperformance. **Arguments Against the Influence of Family Background on Educational Achievement** *Peer Influence and Sub-Cultures*: While family background plays a role, peer groups and student sub-cultures can also significantly impact educational achievement. Students who belong to academic-oriented peer groups may be more likely to excel in school, while those influenced by anti-school sub-cultures may underperform academically. *Teacher Expectations and School Policies*: The expectations of teachers, the presence of streaming practices, and the influence of school policies can all shape educational outcomes. The phenomenon of the self-fulfilling prophecy, where students fulfill the expectations placed upon them, highlights how external factors can impact academic success. *Private vs. State Schools*: Disparities between private and state schools, such as smaller class sizes, better resources, and more experienced teachers, can lead to differences in educational achievement. The systemic advantages present in private schools may outweigh the influence of family background on academic success. **Conclusion** In conclusion, while family background certainly plays a vital role in shaping educational achievement through various material, cultural, and social influences, it is important to recognize that other factors such as peer groups, teacher expectations, and school policies also significantly impact academic outcomes. A comprehensive understanding of the interplay between family background and these external influences is essential for devising effective strategies to promote educational equity and success for all students.

O level and GCSE

To what extent does family background influence educational achievement? In interpreting 'family background', candidates may discuss factors such as ethnicity, religion, social class, locality, culture, etc. Candidates should show awareness of the ways that family background may influence educational achievement. This influence could be cultural and/or material. In evaluation, they should consider how these family factors may not influence educational achievement and discuss how other factors such as school/peer group can be influential instead. Possible answers: For: - Material factors – children living in poverty are likely to be educationally disadvantaged i.e. over-crowded accommodation, part-time jobs, few resources to support education at home, etc. - Cultural factors – members of the working class are thought to want immediate rather than deferred gratification and therefore value education less than middle-class parents. - There may be an absence of successful role models in the family who have done well in education, and therefore this route is not seen as an option for many children. - Bourdieu's theory of cultural capital – familiarity with literature, visits to museums and galleries, and knowledge of how the education system works are seen to advantage some children in education. - Gender roles – girls may be socialised to see their future roles in terms of marriage and children and not in terms of educational success. - Bernstein's theory – believes the working class use a restricted code and the higher classes use an elaborated code at home, which makes the 'world' of education far easier to access and be successful in. - Minority students may be taught in a language that is not their home language and so may face problems of understanding and of written/verbal expression. - Other reasonable responses. Against: - Pupil sub-cultures may be influential over educational achievement (pro or anti-school sub-cultures); the set/stream a pupil is in may be a very important factor in determining educational achievement. - Teacher expectations may affect educational achievement through labeling and the self-fulfilling prophecy or the halo effect. - Students in private schools typically achieve better educational qualifications than those in state schools, perhaps due to smaller class sizes, better resources, and better teachers. - The ethnocentric curriculum may be a reason why ethnic minority students do less well in education than others. - Schools can be seen as institutions that reinforce traditional gender roles through careers advice, subject choice, etc., and this can affect educational achievement. - A culture of masculinity is encouraged in many peer groups, making it very difficult for males to be hardworking and studious in school. - Government/school policy may influence educational achievement more than family background (e.g., girls aren't always sent to school/compensatory education, etc.). - Other reasonable responses. (15 Marks) 0495/22 Cambridge IGCSE – Mark Scheme PUBLISHED May/June 2019 © UCLES 2019 Page 13 of 27 Question Answer Marks 2(e)

Essay on Effect Of Family Background To Students Academic Achievement

Students are often asked to write an essay on Effect Of Family Background To Students Academic Achievement in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Effect Of Family Background To Students Academic Achievement

Introduction.

Family background plays a crucial role in a student’s academic achievement. It can shape the way students view education, their attitude toward learning, and their academic success.

The Role of Parents

Parents are the first teachers. They can influence their children’s academic performance through their attitudes towards education, their support, and their involvement in their children’s schooling.

Economic Status

The economic status of a family can also affect a student’s academic performance. Families with more resources can provide better educational materials and opportunities, which can lead to better academic outcomes.

Home Environment

A supportive and stable home environment can foster a love for learning. This can motivate students to perform better academically.

In conclusion, family background can significantly influence a student’s academic achievement. It is important for families to provide a supportive and conducive environment for learning.

250 Words Essay on Effect Of Family Background To Students Academic Achievement

The family is the first school for any child. It plays a significant role in shaping a child’s academic journey. This essay explores how a student’s family background can influence their academic achievement.

Family’s Financial Status

The financial condition of a family can directly affect a student’s academic performance. Families with good financial health can provide resources like books, computers, and private tutors to help their children excel. On the other hand, students from families struggling financially may not have access to such resources, which can limit their academic progress.

Educational Background of Parents

Parents’ education level also impacts a student’s academic achievement. Parents who are well-educated can guide their children in their studies. They understand the importance of education and encourage their children to focus on their academics.

Family Environment

The environment at home is another key factor. A peaceful and supportive environment helps students focus on their studies. In contrast, a stressful or disturbed family environment can distract students and hinder their academic performance.

Parental Involvement

Parents actively involved in their children’s education can boost their academic success. They can monitor their children’s progress, help with homework, and motivate them to do better.

In conclusion, a student’s family background plays a crucial role in their academic achievement. The financial status, parents’ education level, family environment, and parental involvement can all influence a student’s academic performance. Therefore, it’s important for all families to provide a supportive environment for their children’s academic growth.

500 Words Essay on Effect Of Family Background To Students Academic Achievement

Family background plays a vital role in shaping a student’s academic success. It’s like a foundation that supports the growth of a student’s learning. This essay will discuss how family background impacts a student’s academic achievement.

Parental Education

Parents’ level of education is a key part of a family background. If parents are well-educated, they can guide their children in their studies. They can help with homework and explain complex topics. This support can boost a student’s performance in school. On the other hand, parents with less education may find it hard to assist their children acadically.

A family’s economic status can also affect a student’s academic achievement. Families with higher income can afford resources like books, computers, and private tutors. These resources can help students learn better. But families with lower income might struggle to provide these resources.

Family Structure

The structure of a family, whether it’s a single-parent or two-parent family, can impact a student’s academic success too. In a two-parent family, responsibilities like helping with homework can be shared. This can result in better academic support for the student. In single-parent families, the parent might be too busy to provide the same level of support.

Parents who are involved in their child’s education often have a positive impact on their academic achievement. When parents show interest in their child’s schoolwork, the child feels encouraged to perform better. If parents are not involved, the child might feel less motivated to excel acadically.

A peaceful and supportive home environment can help a student focus on their studies. If a home is noisy or stressful, it can be hard for a student to concentrate on their schoolwork. This can lead to poor academic performance.

In conclusion, family background can significantly affect a student’s academic achievement. Factors like parental education, economic status, family structure, parental involvement, and home environment all play a part. Therefore, it’s important for families to provide a supportive environment for their children’s academic success. This includes helping with schoolwork, providing resources, and showing interest in their child’s education.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Effect Of Drug Abuse

- Essay on Effect Of Cryptocurrency On Economy

- Essay on Educational Tour

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Which program are you applying to?

Accepted Admissions Blog

Everything you need to know to get Accepted

July 10, 2022

Stanford University School of Medicine Secondary Application Essay Tips & Deadlines [2022 – 2023]

![family and educational background essay Stanford University School of Medicine Secondary Application Essay Tips & Deadlines [2022 - 2023]](https://blog.accepted.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Stanford_Essay_Tips_2022-2023.jpg)

Ranked #8 for research by U.S. News , Stanford University SOM provides a strong foundation in the basic sciences and the opportunity to select a scholarly concentration—to pursue topics of individual interest. Students are provided with a mentor, coursework and research opportunities in the topic of their choice. This medical school strongly prefers an extensive background in research and leadership experience.

Stanford University School of Medicine 2022-2023 secondary application essay questions

Stanford medical school essay #1: practice setting.

What do you see as the most likely practice scenario for your future medical career? Choose the single answer that best describes your career goals and clinical practice setting:

- Academic Medicine (Clinical)

- Academic Medicine (Physician Scientist)

- Non-Academic Clinical Practice

- Health Policy

- Health Administration

- Primary Care

- Public Health/Community Health

- Global Health

Why do you feel you are particularly suited for this practice scenario? What knowledge, skills and attitudes have you developed that have prepared you for this career path? (1000 characters)

In asking this question, the school wants to determine how extensive your clinical experience is and how knowledgeable you are about the different methods of medical care delivery. Be honest in selecting the area of your interest. By describing the experience you have in this area to explain why you prefer it over others, you will convince the adcom of your realistic understanding of the practice of medicine. Create a list of “knowledge, skills and attitudes” to explain as support for your interest in this field. Your conclusion could provide an explanation for how and why their program would be the best to support your pursuit of a career in this arena.

Stanford Medical School essay #2: Curricular Interests

How will you take advantage of the Stanford Medicine Discovery Curriculum and scholarly concentration requirement to achieve your personal career goals? (1000 characters)

Given the unique feature of their curriculum, the scholarly concentration , review the possibilities and select those that reflect your research background and interests. How extensive is your research experience in this area? Do you have training in special techniques or laboratory methods in this area? How will the mentorship, coursework and research experience available at Stanford University SOM assist you in meeting your academic and professional goals? If your prior research experience has allowed you to impact the delivery of medical care, how will further expertise and experience enhance your contribution to patient care?

Stanford Medical School essay #3: Background

Describe in a short paragraph your educational and family background. (E.g., I grew up in New York City, as the 3rd child of a supermarket cashier and a high school principal. I attended Mann High School where my major interests were boxing and drama.) (600 characters)

So often education and family go together. How does your family value education? Do you come from a family of doctors, or are you a first generation college graduate? A family is a legacy, in a way. So often how we were raised influences our path – sometimes congruently – “as my parents did, and as I will do too.” Sometimes an ambitious educational journey happens as a rebound – “my father worked two jobs with very little fulfillment, and I loved school, was good at it, and wanted to change our lives.” How did you come to value education, envision yourself as a doctor, in light of how you grew up?

Stanford Medical School essay #4: Contribution to Learning Environment

The Committee on Admissions regards the diversity (broadly defined) of an entering class as an important factor in serving the educational mission of the school. You are strongly encouraged to share unique attributes of your personal identity, and/ or personally important or challenging factors in your background. Such discussions may include the quality of your early education, gender identity, sexual orientation, any physical challenges, or any other life or work experiences. (2000 characters)

Using the list provided above, “ unique attributes of your personal identity, and/ or personally important or challenging factors in your background. Such discussions may include the quality of your early education, gender identity, sexual orientation, any physical challenges, or any other life or work experiences,” free write a response to each item. To free write, simply give yourself five minutes or longer to jot down any experiences you have had that fit the description given. Try not to use examples that you have already used in your primary application essays or in other Stanford essays. Using those descriptions, select the most relevant for this response—those that may also fit the mission and goals of the school’s curriculum . Create an outline and use this to stay on topic. What transitions will you use to connect the experiences? What did you gain, from a bigger picture perspective, from those experiences and how will they benefit your classmates? This essay is pretty broad, but it’s also longer than the others, so you should strive in the final draft to be organized with what you present.

What is distinct about you that makes you stand out from a “traditional” applicant?

Stanford Medical School essay #5

Please describe how you have uniquely contributed to a community with which you identify. ( 1,000 characters )

Prompt #4 is about who you are, and prompt #5 is about action in relation to who you are. It is important to Stanford that you are a do-er. Are you active in community service at a mosque in your community? If you identify with the LGBTQ community, do you volunteer for a crisis hotline (considering the higher rates of self-harm and suicidality in this community)? Do you teach second language classes or participate in an after school program to help high school children in poor communities have a safe place to interact and get help with homework? Did you participate in a march for Black Lives Matter or the overturning of Roe vs. Wade? What is the significance of this contribution? How is this action a contribution to a community with which you identify? What is the purpose of this activity; to what ends does it support the community?

Stanford Medical School essay #6

Please describe an experience/situation when you advocated for someone else. (1000 characters)

We have the responsibility to speak up, support, intervene, or effect change, when we observe a situation that’s not right, observe discrimination, understand someone’s struggle that could be lessened or alleviated with assistance or solidarity. When did you help someone because it was the right thing to do? When did you help someone because they were disadvantaged and you had ability, in whatever capacity this is true. This prompt is asking you for an action, not just an observation, about social justice.

Stanford Medical School essay #7: Special Insights (Optional)

Please describe any lessons, hardships, challenges or opportunities that resulted from the global COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, describe how these insights have informed your motivations and preparation for medical school in areas of academics, research, employment, volunteer service and/or clinical experiences. (1000 characters)

It’s likely this prompt is a place for Stanford to easily and uniformly locate information on how applicants were affected by COVID-19, across applications. That’s practical. So, stay clear and categorize your response in the manner they ask: academic, research, employment, volunteer service, and clinical experience. Be concise and direct. You don’t have a lot of room to respond, so stay factual.

Also, consider the “lesson” for this prompt. You have a brief opportunity to place in context the effect of a public health crisis that no one could foresee. How do you, a future doctor, foresee the direction of patient care in light of this pandemic? How did COVID give you an opportunity to ease the burden of the pandemic on others, especially the vulnerable? Did you take the initiative to help them? What did you do and learn? How did the pandemic motivate you in your pursuit of medicine?

Stanford Medical School essay #8 (Optional)

Please include anything else that will help us understand better how you may uniquely contribute to Stanford Medicine? (1000 characters)

This is an optional essay that gives you space to discuss anything else relevant to your application to Stanford. You should not repeat earlier material. This can include specific experiences that you would like to explain or a specific connection to Stanford on which you want to elaborate for the admissions committee.

While the prompt says the essay is optional, it is also an opportunity for any applicant to think about ways they will add to the class that they haven’t already covered. If there are additional ways that you can contribute, you definitely want to share them with Stanford’s admissions committee. This may be a moment to solidify your suitability for research and leadership since Stanford clearly seeks out applicants who have strong experience in either of these two areas, or both. What have you done, and what you will do – told with a point of view that does not replicate an activity description or MME.

Applying to Stanford University School of Medicine? Here are some stats:

Stanford SOM median MCAT score: 517

Stanford SOM median GPA: 3.89

Stanford SOM acceptance rate: 1.4%

U.S. News ranks Stanford #8 for research and #30 for primary care.

Check out the Med School Selectivity Index for more stats.

You’ve worked so hard to get to where you are in life. Now that you’re ready for your next achievement, make sure you know how to present yourself to maximum advantage in your medical school applications. In a hotly competitive season, you’ll want a member of Team Accepted in your corner, guiding you with expertise tailored specifically for you. Check out our flexible consulting packages today!

Stanford University School of Medicine 2022-2023 application timeline

Source: Stanford University School of Medicine website

Related Resources:

- 5 Fatal Flaws to Avoid in Your Med School Essays , a free guide

- Secondary Strategy: Why Do You Want To Go Here?

- Applying to the Stanford Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program: Everything You Need to Know

About Us Press Room Contact Us Podcast Accepted Blog Privacy Policy Website Terms of Use Disclaimer Client Terms of Service

Accepted 1171 S. Robertson Blvd. #140 Los Angeles CA 90035 +1 (310) 815-9553 © 2022 Accepted

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Adolescent Family Experiences and Educational Attainment during Early Adulthood

Janet n melby, rand d conger, shu-ann fang, k a s wickrama, katherine j conger.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence regarding this article should be addressed to Janet N. Melby, Institute for Social and Behavioral Research, Iowa State University, 2625 North Loop Drive, Suite 500, Ames, IA 50010-8615. Electronic mail may be sent via Internet to [email protected]

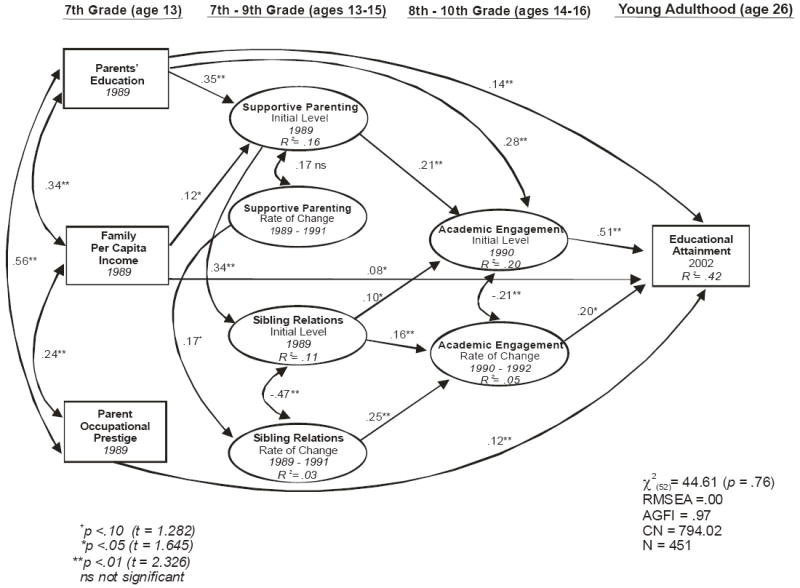

This study investigated the degree to which a family investment model would help account for the association between family of origin socioeconomic characteristics and the later educational attainment of 451 young adults (age 26) from two-parent families. Parents’ educational level, occupational prestige, and family income in 1989 each had a statistically significant direct relationship with youths’ educational attainment in 2002. Consistent with the theoretical model guiding the study, parents’ educational level and family income also demonstrated statistically significant indirect effects on later educational attainment through their associations with growth trajectories for supportive parenting, sibling relations, and adolescent academic engagement. Supportive parenting and sibling relations were linked to later educational attainment through their association with adolescent academic engagement. Academic engagement during adolescence was associated with educational attainment in young adulthood. These basic processes operated similarly regardless of youths’ gender, target youths’ age relative to a near-age sibling, gender composition of the sibling dyad, or gender of parent.

Keywords: educational attainment, academic engagement, parenting, sibling relations, SES

Substantial evidence indicates that the number of years of formal schooling completed by early adulthood is associated with young adults’ initial labor market status and income ( Bjarnason, 2000 ), later occupational success ( Blau & O. D. Duncan, 1967 ; Chand, Crider, & Willits, 1983 ), and life satisfaction and healthy aging in general ( Meeks & Murrell, 2001 ). Prior research identifies relationships between youth educational outcomes and family of origin characteristics such as parental support and family income (e.g., Best, Hauser, & Allen, 1997 ; Brooks-Gunn, G. J. Duncan, & Aber, 1997 ; Furstenberg, Eccles, Elder, Cook, & Sameroff, 1999 ; Melby & R. D. Conger, 1996 ; Sieben & DeGraaf, 2003 ). Recent literature also suggests that siblings may be associated with youth educational outcomes ( G. J. Duncan, Boisjoly, & Harris, 2001 ). Less is known, however, about the combined effects of these family factors on educational attainment ( Connell & Halpern-Felsher, 1997 ). Moreover, despite considerable evidence for the effects of socioeconomic factors on parenting and child development (e.g., see Bornstein & Bradley, 2003 ; Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, 1997 ; R. D. Conger & Dogan, 2007 ; McLoyd, 1998 ; White, 1982 ), there is increasing awareness of the need to identify possible family pathways through which specific indicators of socioeconomic status (SES) are related to eventual academic and occupational success ( Bradley & Corwyn, 2002 ; Conger & Donnellan, 2007 ; Lerner, 2003 ; McLoyd, 1998 ). We address these issues and extend the existing literature by evaluating a conceptual model which proposes that family SES will be associated both directly and indirectly with adult educational attainment.

The Conceptual Model

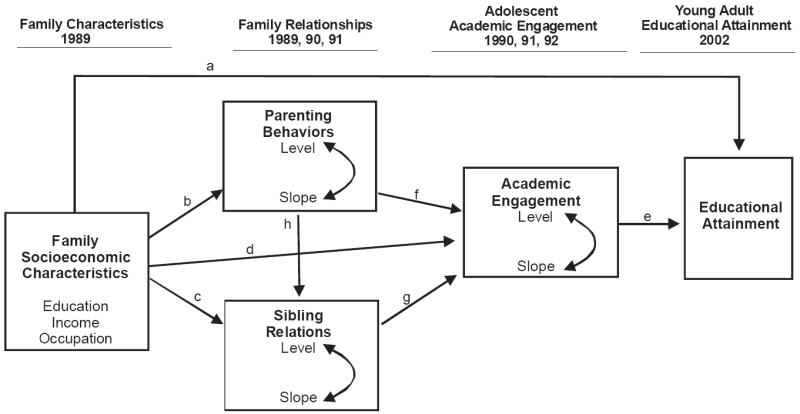

We draw on what Conger and his colleagues have called the family investment model to develop the conceptual framework for the present study ( R. D. Conger & Dogan, 2007 ; R. D. Conger & Donnellan, 2007 ). According to the investment model, family SES in the form of parental income, education, and occupational status is positively related to parental investments in children. These investments can take many forms but center especially on parental support for creating a family environment that fosters the development of human capital for children. Although there is growing recognition of the dynamic nature of the relationships among family characteristics and educational outcomes (e.g., Crosnoe, 2004 ; Crosnoe, Mistry, & Elder, 2002 ), ours is the first known application of the investment model to the issue of early adult educational attainment, as illustrated in Figure 1 . Specifically, we propose that family socioeconomic characteristics will affect later educational attainment both directly and indirectly through their influence on interpersonal relationships in the family and adolescent engagement in academic pursuits. Supportive parenting and positive sibling relationships, which constitute direct investments in a family environment that fosters the academic success of children, are hypothesized to influence academic engagement during early and mid adolescence prior to the transition to adulthood. Adolescent academic engagement is proposed to be the primary pathway through which these family characteristics affect eventual educational attainment. We next describe the theoretical and empirical underpinnings for each path in the conceptual model.

Proposed model for the influence of family interpersonal relationships and adolescent academic engagement on linkages between family socioeconomic characteristics and educational attainment in early adulthood.

Socioeconomic Characteristics and Educational Attainment

Extensive previous research across a range of studies has shown that family socioeconomic status (SES) is associated with child outcomes. In our model, family socioeconomic characteristics are proposed to have statistically significant direct relationships with educational attainment in young adulthood (Path a in Figure 1 ; e.g., Ensminger & Fothergill, 2003 ; Hill & G. J. Duncan, 1987 ; Hollingshead, 1975 ; Travis & Kohli, 1995 ). The support for this path derives from the accumulating evidence that access to “capital” in the form of more highly educated parents in higher status occupations with above average incomes facilitates subsequent pursuit of advanced education (e.g., see Coleman, 1988 ; Lin, 2001 ; McLoyd, 1998 ). These effects are believed to result from the initial and cumulative opportunities associated with greater economic resources (e.g., G. J. Duncan & Magnuson, 2003 ; Mayer, 1997 ). Although we propose that SES will be indirectly related to educational attainment through family and academic experiences during adolescence, we also include the direct path from SES to attainment because parents serve as role models for pursuing advanced education and also provide access to interpersonal and economic resources that facilitate the acquisition of additional years of schooling. That is, the interpersonal processes proposed in the model in Figure 1 only are concerned with the relationship aspects of the family investments. SES also increases monetary investments in children that facilitate continued education and these unmeasured resources are captured by path a in the model.

There is considerable evidence of the effects of SES on educational outcomes. For example, in a meta-analysis of almost 200 studies, White (1982) identified an average correlation between family SES and youth academic achievement of .22. A more recent meta-analysis of this relationship by Sirin (2004) using over 50 studies published between 1999 and 2000 found an average correlation of .29. As noted by Oakes and Rossi (2003) , however, the interpretation of SES effects is complicated by the disparate ways in which SES has been assessed. We are especially interested in the direct effects of three frequently used markers of SES on educational outcomes. There is ample support that parents’ education (amount of formal education) is associated with greater educational attainment by children (e.g., Blau & O. D. Duncan, 1967 ; Haveman, Sandefur, Wolfe, & Voyer, 2004 ). Although the extent of the association varies, several studies suggest a positive relationship between parents’ education and youths’ years of schooling completed ( G. J. Duncan, Yeung, Brooks-Gunn, & Smith, 1998 ; McLoyd, 1998 ; Tomlinson-Keasey, & Little, 1990 ). For example, using data from the Children of the National Longitudinal Surveys of Youth data set, mother educational attainment and youth college enrollment at age 20-22 years correlated .21 ( McLeod & Kaiser, 2004 ). In other research, educational attainment for parents and youth age 28-29 years correlated .44 ( Benin & Johnson, 1984 ). In terms of family income , evidence suggests that family income has a modest relationship with academic achievement during childhood but has a more robust relationship with academic attainment in adulthood ( G. J. Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 1997 ). The connection between poverty and lower educational attainment among children and adolescents has been well documented (e.g., Crosnoe, Mistry, & Elder, 2002 ; McLanahan, 1985 ; McLeod & Kaiser, 2004 ; McLoyd, 1998 ; Sewell & Hauser, 1980 ). Parents’ occupational status has long been associated with variation in children’s educational assessments ( Biblarz & Raftery, 1999 ; Korupp, Ganzeboon, & Van Der Lippe, 2002 ). Occupational status for both mothers and fathers is related to children’s eventual educational attainment. For example, fathers’ occupational status measured using Duncan’s Socioeconomic Index and youths’ educational attainment at age 28-29 years correlated .47 ( Benin & Johnson, 1984 ). Moreover, mother’s occupational status has been shown to have a strong effect on children’s schooling, independent of father’s education and occupation ( Kalmijn, 1994 ). Finally, in terms of the relative strength of the relationship of the three SES indictors with academic achievement, White’s (1982) meta-analyses identified family income as the highest correlate, followed by parental occupation and parental education. In the next section we consider the hypothesized indirect pathways through which SES is associated with educational attainment.

Mechanisms of SES Influence

As previously noted, in addition to proposing direct effects of SES on educational attainment, we draw upon the family investment model ( R. D. Conger & Donnellan, 2007 ) to predict that the effects of SES on educational attainment will operate indirectly through several mediating variables. This prediction is consistent with McLoyd’s (1998) extensive review of the literature which shows that the link between socioeconomic disadvantage and child outcomes appears to be mediated partially by harsh, inconsistent parenting. Our model also is consistent with work by Schoon et al. (2002) and by Crosnoe and associates (2002 , 2004 ) which examine processes through which social inequalities experienced during childhood are associated with adult achievements. We next discuss the effects of SES on each mediator of the relationship between SES and educational attainment as proposed in our theoretical model.

SES effects on supportive parenting and positive sibling relationships

According to the family investment model , higher compared to lower SES parents are more likely to commit time, energy and support in raising their children. Moreover, they are especially likely to place an emphasis on academic success and to create a richer learning environment for their children ( R. D. Conger & Donnellan, 2007 ). Consistent with this perspective, in our model family socioeconomic characteristics are expected to have a statistically significant direct effect on both the initial level and changes in supportive parenting behaviors (Path b in Figure 1 ). This theoretical prediction is consistent with a multitude of empirical findings demonstrating a positive association between family SES and specific qualities of parenting behaviors that foster learning and academic success (for recent reviews see R. D. Conger & Dogan, 2007 and R. D. Conger & Donnellan, 2007 ). For example, family resources such as higher parental income, education, and occupational status are associated with the quality of parenting ( Bornstein & Bradley, 2003 ). Such advantages appear to promote supportive and inhibit hostile parental behaviors toward an adolescent child ( Cui, Conger, Bryant, & Elder, 2002 ). In the current model, however, we extend the usual investment perspective by proposing that SES affects not only parents but also siblings and the degree to which they promote one another’s academic involvements.

In the model, SES is proposed to be directly related to both the initial level and change in the quality of sibling relations (Path c in Figure 1 ; e.g., Dunn, 2007 ; Dunn, Slomkowski & Bearsall, 1994 ; Hao & Matsueda, 2006 ; MacKinnon, 1988 ). Compared with those from lower SES families, 12-13 year old siblings from higher SES families reported more warmth and intimacy in relationships with siblings ( Dunn, 1996 ). Research with youth ages 19-33 years demonstrated that stressful family economic conditions are associated with less overall sibling communication and more sibling conflict ( Milevsky, Smoot, Leh, & Ruppe, 2005 ). We propose that SES leads to a family environment that is generally more positive with regard to academic efforts, and for that reason add sibling relationships to the investment model.

SES effects on adolescent academic engagement

We also predict a direct relationship between SES and adolescent academic engagement (Path d, Figure 1 ; e.g., Ensminger & Slusarcick, 1992 ; Rabusicova, 1995 ). Academic engagement in our model is defined as a youth’s positive attitude toward school, confidence in own ability to do well in school, and perception of and actual success in school ( Anderson, Christenson, Sinclair, & Lehr, 2004 ; Connell, Spencer, & Aber, 1994 ). Research by Schoon et al. (2002) using data from two national birth cohorts in Britain found lower family of origin SES (assessed by occupational status) was related to lower academic adjustment and performance in childhood and adolescence, which in turn was associated with lower SES when these youth were in their 30s. Other support for this prediction comes from evidence previously cited for the effects of SES on educational outcomes. As with the direct path from SES to later educational attainment, we include the direct path to academic engagement to accommodate the expected influence of unmeasured investments related to SES, such as funds for extracurricular educational experiences such as tutoring and enrollment in special educational programs beyond normal schooling ( R. D. Conger & Donnellan, 2007 ).

Effects of Family Interpersonal Relationships

The next step in the proposed model involves the role of family relationships in promoting academic engagement. Because earlier research suggests that parents and siblings have unique effects on many domains of adolescent development ( Bank et al., 2004 ; K. J. Conger, R. D. Conger, & Scaramella, 1997 ; Crosnoe & Elder, 2004 ; Moser & Jacob, 2002 ), we propose additive influences on engagement for parenting behaviors and sibling relations.

Supportive parenting behaviors

Much previous research has demonstrated an association between type of parenting and adolescents’ school-related success (Path f in Figure 1 ; e.g., Steinberg, Lamborn, Dornbusch, & Darling, 1992 ). Parents affect youths’ academic confidence ( Rodgers & Rose, 2001 ) and school adjustment ( Ingoldsby, Shaw, & Garcia, 2001 ). Authoritarian parents tend to have adolescent children with a lower grade-point-average (GPA), whereas authoritative parenting is positively associated with school performance ( Dornbusch, Ritter, Leiderman, Roberts, & Fraleigh, 1987 ; Steinberg, Mounts, Lamborn, & Dornbusch, 1991 ). Authoritative parenting positively relates to adolescents’ better peer relationships ( Chen, Dong, & Zhou, 1997 ) and adolescents’ greater engagement in school ( Steinberg et al., 1992 ). The primary conclusion from research in this area is that parents who are supportive and communicate well with their children, are involved in their children’s lives, and who refrain from harsh and angry exchanges with their children will have offspring who tend to be more engaged and successful in academic pursuits ( Conger & Donnellan, 2007 ; Melby & Conger, 1996 ; Crosnoe, 2004 ).

Positive sibling relations

Although there has been little research on the possible effect of siblings on academic outcomes, there is growing recognition of the importance of siblings and sibling relationships for child and adolescent development. Siblings often provide advice and guidance about competent behaviors ( Bryant, 1989 ; Dunn, 1996 ), as well as support and companionship ( Cicirelli, 1980 ; K. J. Conger, R. D. Conger, & Elder, 1994 ; Goetting, 1986 ; Tucker, McHale, & Crouter, 2001 ). Recent evidence suggests that sibling influences may extend to school-related success, as hypothesized in Path g in Figure 1 (e.g., G. J. Duncan et al., 2001 ). For example, Amato (1989) found that positive qualities of sibling relations, as well as parenting, were associated with adolescent school-related competencies in several areas that could influence academic performance. His study showed that adolescents who interact positively with siblings at home are more likely to enjoy aspects of school life such as positive peer interactions and learning. In addition, Brody, Stoneman, Smith, and Gibson (1999) found that self-regulated children tend to have lower conflict with siblings, which may indirectly impact success in school. Thus, we suggest that the quality of both parenting and sibling relationships will be associated with adolescent academic engagement. That is, positive and supportive parental and sibling relations are expected to be related to youth’s positive attitude toward school, confidence in own ability to do well in school, and perception of and actual school success.

Joint effects of family relationships

Parent and sibling relationships are intertwined, however, and evidence from multiple investigations suggests that parenting is associated with the quality of sibling relations (Path h in Figure 1 ; e.g., MacKinnon-Lewis, Starnes, Volling, & Johnson, 1997 ; McHale, Updegraff, Tucker, & Crouter, 2000 ; Volling & Belsky, 1992 ). Compared with mothers who were less rejecting, middle-childhood sibling dyads whose mothers were more rejecting were more aggressive in their interactions ( MacKinnon-Lewis et al., 1997 ). Additionally, parental hostility increased conflict between siblings which, in turn, was associated with emotional and behavioral problems for a target adolescent ( K. J. Conger, R. D. Conger, & Elder, 1994 ).

Other evidence points to both unique and cumulative effects of negative relationships with parents and siblings on school adjustment ( Brown, 2004 ; R. D. Duncan, 1999 ). For example, negative parent and sibling relations were independently associated with poor relationships with teachers and peers for preschoolers ( Ingoldsby et al., 2001 ; Vondra, Shaw, Swearingen, Cohen, & Owens, 1999 ). If similar processes occur during adolescence, the effects of multiple negative family relationships could impact later academic outcomes. Amato (1989) found that as children enter adolescence, their general competency becomes more closely associated with the degree of parental control and the quality of sibling relations. Thus, there is reason to believe that in addition to the unique effects of parenting and siblings on adolescent outcomes, parenting behavior is related to the quality of sibling relations in a manner that may have important implications for adolescent development, including academic engagement. In the model we hypothesize that the effects of family interpersonal relationships on educational attainment at young adulthood will operate through academic engagement during adolescence.

Direct effects of Academic Engagement

As a final step in the hypothesized causal processes, our model proposes a statistically significant direct association between adolescent academic engagement and educational attainment (Path e in Figure 1 ; Wang, Kick, Fraser, & Burns, 1999 ). Previous research demonstrates an association between attachment to school and school performance (e.g., Cernkovich & Giordano, 1992 ; Juang & Silbereisen, 2002 ; Wade & Brannigan, 1998 ) and between school motivation and academic achievement ( Guo, 1998 ; Pintrich, 2000 ; Roeser, Eccles, & Sameroff, 1998 ; Wentzel & Feldman, 1993 ). Recently, Marjoribanks (2006) found that adolescent cognitive habitus, conjointly defined by adolescent academic achievement and attitudes about school, was related to their educational attainment as young adults. The previously cited study by Schoon et al. (2002) also found lower academic adjustment and performance in childhood and adolescence to be associated with lower SES when youth reached adulthood. Overall, these earlier research findings are consistent with path e in the conceptual model. The goal of the present study is to evaluate the empirical credibility of the proposed conceptual framework by using data from an ongoing cohort study of youth from early adolescence to the early adult years.

Addressing Limitations in Earlier Research

In addition to being the first to test a specific form of the family investment model as it relates to educational attainment, the current study also addresses several limitations in the research literature. Despite considerable past research suggesting that parent socioeconomic status, parenting, and sibling relationships influence adolescent academic outcomes, there are several limitations in most of this work. First , few studies have examined, in the same analysis, the joint effects of parent-child and sibling relationships on educational attainment. The current study addresses this gap in the literature by including both parents and siblings in the proposed model. Second , much previous research examining family processes and developmental outcomes has used retrospective data that are affected by recall bias resulting from memory failure and the subjectivity of the issue in question (e.g., Aquilino, 1997 ; Barber, 1994 ; Henry, Moffitt, Caspi, Langley, & Silva, 1994 ; Rueter, Chao, & R. D. Conger, 2000 ). We use a prospective longitudinal research design that allows us to examine predictor and outcome variables in the correct temporal order without retrospective reports.

Third , in contrast to investigations that use a single measure of socioeconomic status, we examine three separate components—parent education, occupation, and income. Although frequently combined into a single measure of SES, recent evidence suggests that the extent of influence by individual markers of SES may shift over the course of the lifespan (see Warren, Hauser, & Sheridan, 2002 ), vary according to the outcome assessed (e.g., see G. J. Duncan, Yeung, Brooks-Gunn, & Smith, 1998 ), and operate somewhat differently depending on culture and ethnicity ( Bradley & Corwyn, 2003 ; McLoyd, 1998 ). Furthermore, given the lack of uniformity in measurement of SES ( Oakes & Rossi, 2003 ), a number of scholars suggest separating SES into these three frequently used quantitative indicators in order to help understand the independent effects of each of them ( R. D. Conger & Dogan, 2007 ; Corwyn & Bradley, 2005 ; G. J. Duncan & Magnuson, 2003 ; Ensminger & Fothergill, 2003 ). Assessing their unique effects is particularly warranted when evaluating change over time ( Bornstein, Hahn, Suwalsky, & Haynes, 2003 ; Warren et al., 2002 ). This allows us to assess differential associations of these exogenous variables with our endogenous variables.

Fourth , many past investigations of sibling effects have primarily focused on structural factors (e.g., birth order, number of siblings, etc.) and achievement factors (e.g., siblings’ GPA) as opposed to relationship dimensions (e.g., see Hauser, Sheridan, & Warren, 1999 ; Sandefur & Wells, 1999 ; Sieben & DeGraaf, 2003 ). While structural factors are important considerations, there is reason to focus on the quality of the sibling dyad’s interpersonal relations as a potential influence on educational attainment ( K. Conger, Bryant, & Brennom, 2004 ). Fifth , earlier longitudinal analyses typically used traditional regression, including auto-regressive techniques (e.g., Melby & R. D. Conger, 1996 ; Rodgers & Rose, 2001 ; Steinberg et al., 1992 ), which are insensitive to intra-individual differences in change over time. A proper analysis of change requires the examination of specific changes within individuals over time ( Rogosa, Brand, & Zimowski, 1982 ). Therefore, we use growth curve analysis to examine both the absolute levels and individual changes in attributes over time ( T. Duncan, S. Duncan, Stryker, Fuzhong, & Alpert, 1999 ; Willett & Sayer, 1994 ). Sixth , we used multiple informants in the present investigation to improve on past research into family process effects on educational attainment that used single reporters (e.g., Bean, Barber, & Crane, 2006 ; Bowen, Bowen, & Ware, 2002 ), thereby reducing bias by using different reporters for adjacent constructs ( Bank, Dishion, Skinner, & Patterson, 1990 ; Lorenz, Conger, Simons, Whitbeck, & Elder, 1991 ).

Participants and Procedures